Zimbabwe’s new leadership faces a difficult macroeconomic environment.

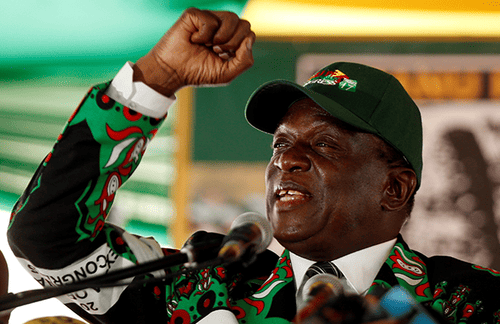

Robert Mugabe, one of Africa’s longest-serving leaders, was ousted from office as Zimbabwe’s president in November, forced out by his country’s military leadership. Mugabe was replaced by Emmerson Mnangagwa, a former ally and a fellow member of ZANU-PF, the current ruling party. Mnangagwa will run for office in this year’s elections.

In addition to the challenges facing new leadership after nearly four decades of an authoritarian regime, Zimbabwe’s new president needs to address the country’s struggling economy and its negative political-economic image in global markets.

Five years of a unity government improved the economy between 2008 and 2013, but were followed by Mugabe’s return to political oppression and economic deterioration. Mugabe’s economic policies, including his land-reform program that expropriated agricultural operations and redistributed farmland, led to a serious decline in agricultural exports and foreign-currency reserves. Zimbabwe today is only the 15th-largest producer of tobacco in the world, while two decades ago it was the fifth.

In addition to the internal structural reforms, Zimbabwe’s new leadership faces a difficult macroeconomic environment. Inflation has reached unsustainable levels, the government abandoned the local currency in 2009, total debt to external lenders has reached more than $7 billion, and a cash shortage and high food prices have put significant pressure on consumers. According to the World Bank, the economy has dropped to only 1% of Sub-Saharan African GDP.

A political change will not necessarily lead to immediate results. “With reengagement with creditors delayed, access to external financing is limited; and the fiscal deficit is being financed by domestic borrowing at an unsustainable pace,” says Ana Lucia Coronel, the Zimbabwe mission chief for the International Monetary Fund (IMF).

The Zimbabwe Industrial Index’s rise of more than 300% in 2017, the biggest gain in global markets, does not reflect the strength of the economy, as Zimbabwean savers and investors turn to stocks due to limited dollar reserves and the weak “bond notes” that the government prints in order to deal with the cash crisis.

Zimbabwe is not alone on the continent in experiencing challenging times. Kenya, the economic hub of East Africa, went through a political crisis in 2017 that eventually led to the recent reelection of president Uhuru Kenyatta. Yet the Kenyan economy has shrunk in recent years, and the IMF confirmed in November that Kenya’s annual GDP growth will fall to 5% in 2017 from 5.8% in 2016.