New regulatory demands are changing banking relationships and, combined with rapid technological change, squeezing transaction banks in the Middle East and North Africa.

In April, the hacking group Shadow Brokers leaked documents that purported to reveal that the US government monitored money flows at some banks in the Middle East. This revelation and its implications for data privacy added to the already momentous challenges facing transaction banking in the Middle East and North Africa (MENA).

Fintechs’ disruption to the traditional banking model, the escalating regulatory burden, notably from the Payment Services Directive (PSD2), and an industry-wide trend of derisking have upended regional correspondent banking relationships. These trends are putting Middle East banks in a bind, just as they are trying to expand.

Additionally, the Shadow Brokers intervention brings into focus the region’s preoccupation with cybersecurity and the preparedness of banks against threats, at a time when pressure for a transition to open banking is sweeping the industry. The issue has gotten the attention of the Bankers Association for Finance and Trade (BAFT). During the inaugural BAFT MENA Bank to Bank Forum, held in Dubai in March, a senior bank executive warned that losses from cybercrime could amount to $3 trillion by 2020.

The aftermath of the global financial crisis has put transaction banking under intense strain. Demands for more-rigorous prudential requirements, economic/trade sanctions, anti–money-laundering and combating-the-financing-of-terrorism (AML/CFT) measures as well as tax-transparency standards have pushed banks to review the banks with which they do business—and curtail some relationships. Profitability concerns aside, the fallout looks reassuringly contained, with isolated examples of interruptions to remittances. Nevertheless, in view of the critical role corresponding banks play in facilitating global trade and economic activity, the struggle of the region’s banks to cope with these problems has been enough to capture the attention of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), which warned in a recent report of the potential systemic threat posed by the downsizing of correspondent banking relationships. So far the fallout in the Middle East has been limited, but broader doubts about transparency could still force international banks to exit some regional relationships.

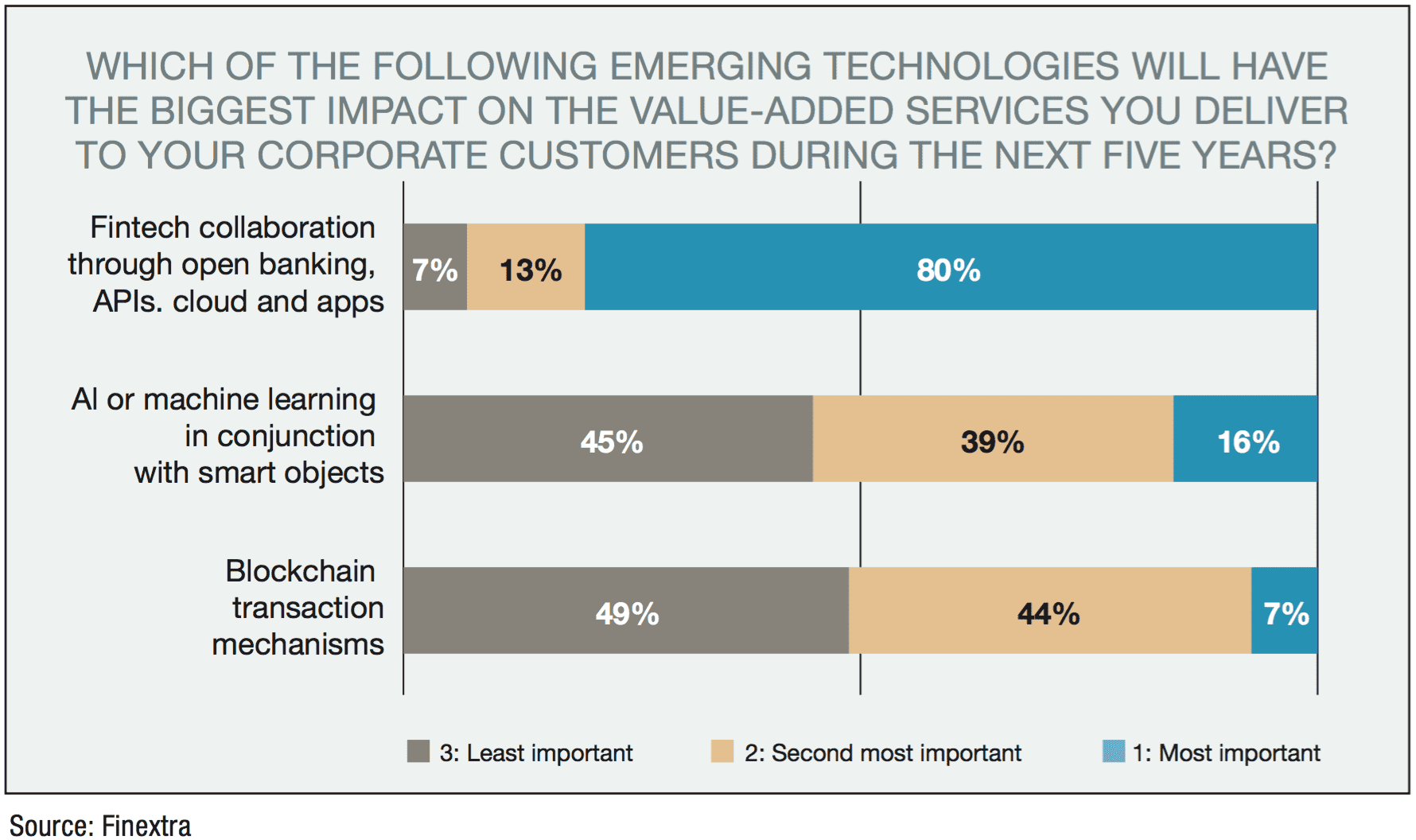

The vacuum created by retrenchment of correspondents has also provided an opportunity for fintechs like Ripple to seize a share of the sizeable market in payments. Since 2011, the number of start-ups in fintech has risen more than 50%, according to PwC. Regulation of the nascent sector is yet to coalesce, but PSD2 is set to allow fintechs to act as intermediaries between banks and their customers, permitting fintechs to coordinate with beneficiary banks to facilitate international fund transfers (see chart, below).

Strategy is crucial and therefore banks must strike a balance between cutting correspondent relationships and avoiding outright capitulation to fintechs. But the warning signs for profits are clear. In a report published in April, the IMF said fintechs could facilitate cross-border flows and act as an alternative to traditional correspondent banking at a fraction of current costs. Meanwhile, the fund said it was also concerned about the potential systemic chain reaction of further retrenchment by correspondents, noting that a growing concentration of cross-border flows could exacerbate financial fragilities in some countries.

There are also worries about the level of readiness of financial-services CEOs in the Middle East. It’s debatable whether they can restructure heavily centralized IT departments to produce more-agile feature-laden digital products and services with a faster speed-to-market, and implementing such fundamental changes while simultaneously lowering costs looks like a daunting prospect.

The onset of real-time payments indicates banks are contemplating erosion in revenues that could lead to further cutbacks in correspondent relationships as profits decline. Despite the limited impact so far in the Middle East, lingering doubts over governance could still prompt a U-turn by international banks. Kuwait, for example, has not faced any correspondent withdrawals—although several domestic banks have severed links with some domestic charities and foreign exchange houses to minimize the perception of risk, the IMF says. In Lebanon, a few foreign banks have cut business relationships with some small Lebanese banks owing to measures introduced by foreign governments regarding money laundering and terrorist financing.

With some analysts saying the Middle East lacks transparency, the caution of some international banks is understandable, as is their diminished risk appetite amid spiralling compliance costs. Fines and sanctions imposed by US regulators amounted to approximately $190 billion between 2008 and 2016, a BAFT panelist stated. Yet all is not doom and gloom; the IMF says Gulf Cooperation Council banks have reacted to criticism and have held discussions with the US treasury since 2015, particularly with respect to AML/CFT standards.

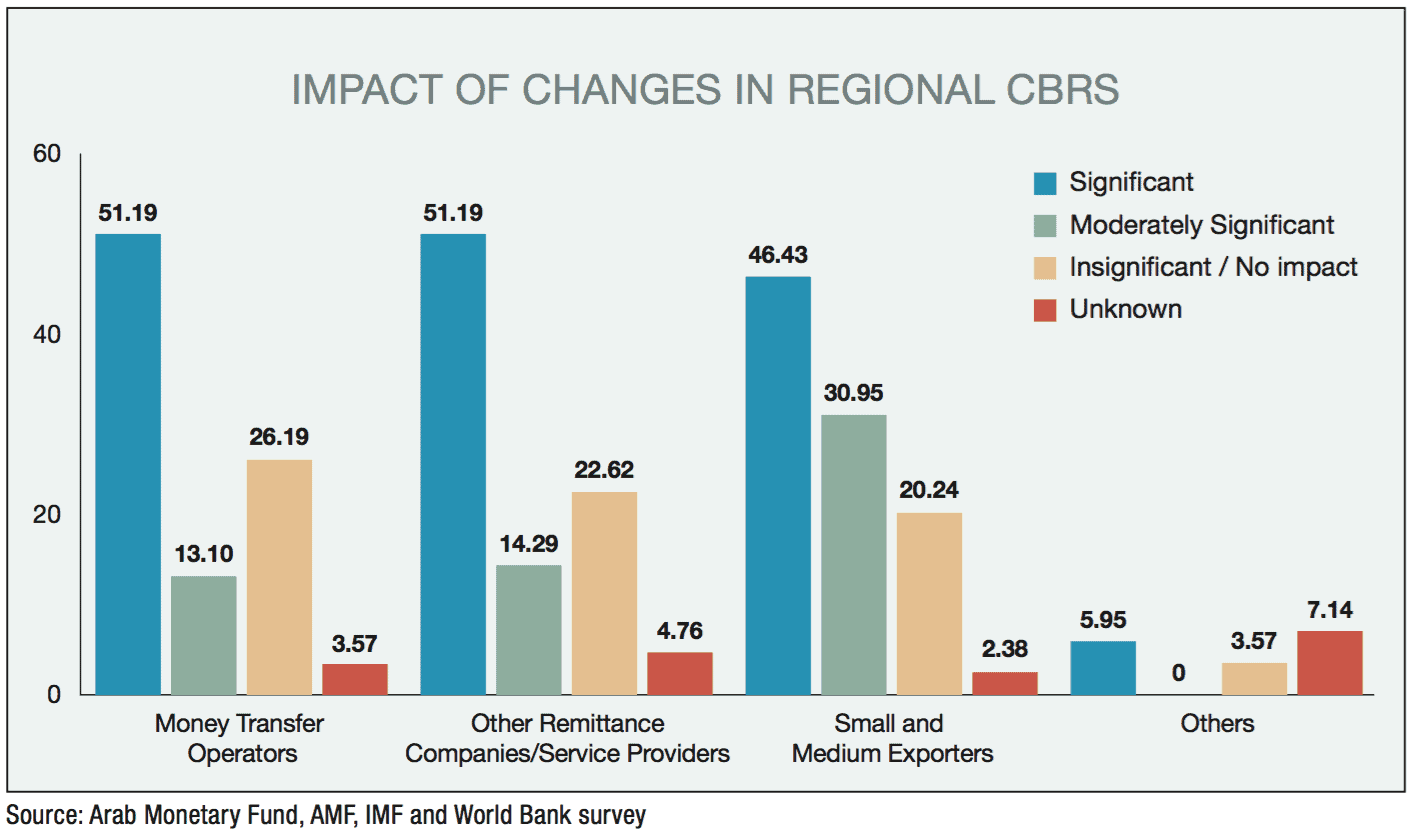

Last year, the Arab Monetary Fund, in conjunction with the IMF and World Bank, surveyed the impact of the changes in regional CBRs. A total of 216 banks in 17 countries participated. While not a definitive guide, the findings offer insights as to where it most affects clients and client segments.

CHALLENGES OF SCALE

Middle East banks are vying with global behemoths that are increasingly turning their attention to transaction banking services. Last year, Citi was ranked the top bank globally in transaction banking by Coalition, an analytics firm.

“Transaction banking is a scale game; and with everyone wanting a piece of the pie, it is a challenging business to succeed in,” says Mark Evans, managing director for transaction banking at ANZ, “especially as we are now in an environment where the cost of compliance has increased, as has the amount of capital that regulators are asking the banks to hold against this business.” He sees competitive pressure driving more industry consolidation.

Banks in the Middle East face the same demands for transformation as multinational giants, even though they don’t have the mass. Discussions over the use of artificial intelligence and robotics dominate their boardrooms, just as they do for their global counterparts. Some are using the new technologies like blockchain and robotics, while others are having trouble catching up. Emirates’ NBD announced a pilot project using blockchain to help secure checks, for example. And Dubai-headquartered Mashreq may become a branchless bank in the future, its CEO said in a statement in May.

Forging alliances with nontraditional partners remains crucial to all banks if they are to unlock new revenues. Blockchain has become highly visible in corporate banking and trade finance, but it is now considered a back-office infrastructure play. That is not to say distributed-ledger technology will not have a vital role to play when it comes to speed, security and cost savings. Ripple, based in San Francisco, has developed a blockchain solution built around its open Interledger Protocol to power real-time payments across different ledgers and networks globally. Ripple’s technology is already deployed by several major banks and payment service providers around the world, including National Bank of Abu Dhabi (recently renamed First Abu Dhabi following a merger) and Turkey’s Akbank.

Marcus Treacher, global head of strategic accounts at Ripple, believes the technology provides new levels of transparency. “In the near term, we are about connecting different parties in cross-border payments transactions, but in the longer term the same distributed-ledger technology that enables these transactions will enable financing organizations to have insight on absolute data to their investments.” Ripple’s technology gives Middle East investors full transactional visibility, which minimizes the risk inherent in current transactions, Treacher says. “Due to the way Islamic or ethical financing is structured, the investor or financier does not have the same recourse and takes on a lot more risk in the venture he is funding.”

Yet despite all the frenzied talk of digital disruption, the benefits are not fully understood by corporate customers in the Middle East. During the BAFT MENA forum, there was a sense banks in the Middle East still have more work to do educating corporate customers. The apparent disconnect is exemplified by the Bank Payment Obligation (BPO), an electronic protocol championed by SWIFT and the International Chamber of Commerce. Following its launch in 2013, the intention was for BPO to play a role in the digitization of trade flows, and serve as an alternative to time-intensive, paper-based payment terms, such as letters of credit. According to the panelists speaking at the forum, Middle East firms still do not understand BPOs. A real-time digital straw poll conducted during the event established that some 44% of audience participants lack knowledge of the product and its role in trade finance.

FINDING MOMENTUM

Despite the upheaval facing transaction banking, its future as a core activity looks assured—at least for banks that can achieve momentum in a sector that is growing. Accomplishing that in the Middle East is probably going to require more mergers akin to the recent joining of National Bank of Abu Dhabi and First Gulf Bank in the United Arab Emirates. If size will be an impending predictor of success, then banking in the Gulf will need to consolidate, perhaps chasing cross-border mergers, to leverage scale.

The rewards for doing so will be enticing to bank boards and their shareholders. The Boston Consulting Group forecasts that account and payment revenues, a key part of transaction banking, will reach $548 billion by 2025, a compound annual growth rate of close to 7%. If the estimates are correct, transaction banking will emerge from relative obscurity and may even surpass its investment banking and equity trading counterparts as a business less susceptible to volatile income streams.

But ANZ’s Evans warns that getting the right model will be a decisive factor. “The ones that will succeed are the ones that maintain a close relationship with their customers and play to their strengths—such as a regional network—have a clear plan and execute it effectively.”

At a time when Middle East banks find themselves in an existential hinterland, a return to stable profits in a growing if unexciting market will be warmly welcomed. The trouble is that happy endings are increasingly hard to find in global financial markets, as uncertainty becomes the new certainty.