Obstacles and contradictions mar Cuba’s environment for foreign direct investment, but its market offers a wealth of opportunity.

The Cuban economy has absorbed several blows in recent decades. The US placed a commercial and financial embargo on the country in 1960, relaxing or tightening restrictions at different times since then. The Cold War ended in December 1991 when Mikhail Gorbachev, then president of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics, dissolved the USSR. This upheaval decimated Cuba’s economy, costing it 80% of its imports and exports.

The US strengthened its embargo in 1992 and 1996 with the Cuban Democracy Act and the Helms-Burton Act, the latter of which applied to foreign countries that traded with Cuba. Companies based outside the US but with American operations were reluctant to invest there because of the Act. “It was not worth having a legal problem with the United States,” explains Paolo Spadoni, associate professor of political science at Augusta University and author of “Failed Sanctions: Why the U.S. Embargo against Cuba Could Never Work” and “Cuba’s Socialist Economy Today: Navigating Challenges and Change.”

Venezuela’s severe financial and economic problems have also hit Cuba hard. Venezuela had been supplying approximately 100,000 barrels of oil daily while Cuba supplied medical teams to Venezuela. Falling commodity prices have dampened Venezuela’s ability to support such arrangements.

“There is no doubt this is a bad [combination] for Cuba at this time because the price of oil is so low,” Spadoni says.

In December 2014, US president Barack Obama called for normalizing relations with the Caribbean nation and eased some travel and financial restrictions. However, the trade embargo remains in place until Congress passes legislation to remove it.

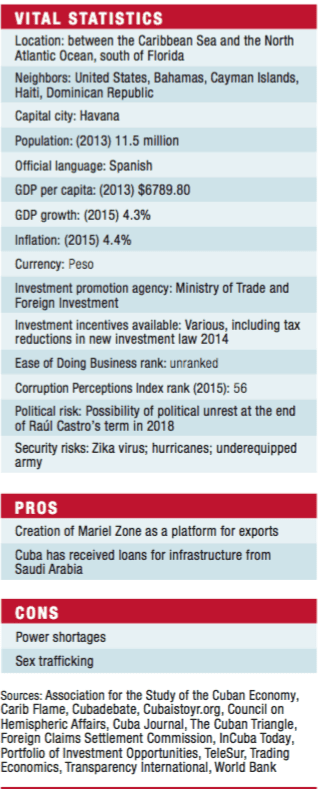

These and other factors could lead to an increase in Cuba’s FDI appetite, according to Mark Entwistle, who has been involved with Cuba for 23 years, formerly as Canadian ambassador to the country and now as managing partner of Toronto-based Acasta Cuba Capital, part of merchant bank Acasta Capital. “For a long time—especially during the decade leading up to 2012—the best way to describe the Cuban attitude to FDI was ‘ambivalent.’ If they could do it without foreign capital as Cuba, Inc., they would do it all by themselves without question,” he says. “They have turned a corner, though. The Cuban attitude to FDI has become decidedly more welcoming in recent years.” Among other measures, the government introduced an investment law in 2014 that kept some of the existing constraints on foreign business but added tax breaks and greater transparency in the decision-making process.

Also in the background is a realization of past lessons, including the dangers of overreliance on individual countries such as the United States, the USSR or Venezuela.

“What Cuba really wants is a diversified set of high-quality partners in areas of priority for its economic development and in which Cubans can participate,” says Entwistle, who still visits the country on business regularly since ending his term as ambassador. What he sees is “a smorgasbord of relationships” with companies from Canada, China, Spain, France, Italy, Japan, the UK, Mexico, Vietnam, Singapore and Russia currently operating on the ground. Not surprisingly, Venezuela’s presence has decreased.

Making an FDI investment succeed means accepting some realities. The removal of the embargo will not necessarily be followed by a tidal wave of investment because Cuba is still a developing country with constraints on its ability to absorb capital. The most successful foreign multinationals will be those that address government priorities, which include tourism, exports (including traditional commodities like rum), light manufacturing to reduce reliance on expensive imports, agriculture, transportation infrastructure, energy, power generation, mineral resource development and undertakings that complement the social contract between individuals and government.

Multinationals that can address those priorities will have a series of advantages, including a stable political environment, a highly educated workforce, pent-up consumer demand, high brand recognition and a rising middle class. “You can see the trend lines to increased consumer buying power,” Entwistle says.

To be sure, multinational investors face several limitations. With few exceptions, including some in the Special Economic Development Zone of Mariel, there are no 100% foreign-owned ventures, with most set up as joint ventures with the government. “The Cuban world view and philosophy is that, effectively, the government is the board of directors for 11.5 million shareholders,” he explains.

Hiring practices are also constrained. Much hiring in a joint venture must be done through a state agency, unless the JV obtains an exemption. Salaries are paid to the agency, and informal payments to workers sometimes become necessary, Spadoni explains.

Moreover, the country has no capital pools and limited access to international capital markets, meaning that, with few exceptions, a foreign multinational has little access to local financing. In some cases, the government side of a joint venture or a development bank will provide some financing, but the government’s prevailing philosophy holds that the state’s contribution to the venture is the commercial opportunity, access to land or other value (such as a tourism destination), natural resources and human capital.

Also unclear at time of writing, the Washington-based Foreign Claims Settlement Commission’s list of outstanding claims from expropriations after the Cuban revolution remains unresolved and amounts to $6 billion to $8 billion. Property claims matter when it comes to FDI because the Helms-Burton law allows US citizens to sue foreign companies that traffic in expropriated properties, according to Spadoni.