CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS

By Gordon Platt

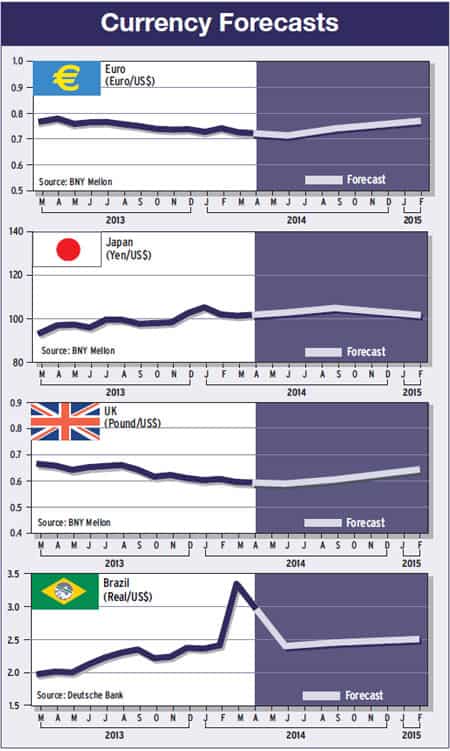

The European Central Bank’s refusal to ease monetary policy in the face of below-target inflation boosted the euro to its highest levels of the year in March, while the British pound rose to a four-year high against the dollar on a strong run of UK economic data. The dollar continued to disappoint market participants looking for a recovery in the greenback.

Alistair Cotton, senior analyst at Currencies Direct, a London foreign exchange broker and international payments provider, says: “The Federal Reserve has been steadfast in reducing its stimulus, while the ECB has almost been going in the opposite direction by hinting at easing monetary policy. Yet, despite expectations that US interest rates will head up before European rates rise, the euro has continued to strengthen.”

ECB president Mario Draghi’s confidence in Europe’s economic recovery, which he said is continuing at a modest pace, caused traders to reconsider their expectations that the central bank would take action to offset weak inflation. “There is some genuine worry that the ECB is not being proactive enough,” Cotton says. “Unemployment is still a major problem in Europe.”

RATES TO STAY LOW

In his press conference last month, Draghi hinted that the ECB would be keeping rates low for an indefinite period. “He wanted the market to know that he still has ammunition left in his locker,” Cotton says. “But Draghi is sounding dovish without doing anything.”

It is going to take the better part of this year for the Federal Reserve to complete its tapering of bond purchases, Cotton adds. “Once the tapering is complete, then we will see interest rates start to increase.”

Both the ECB and the Bank of England chose to leave rates unchanged at their meetings in early March. “The UK economy is expected to continue to recover, but there is some concern that the growth is coming from housing and consumer debt, rather than business investment or exports,” Cotton says.

Axel Merk, president and chief investment officer at Merk Investments, Palo Alto, California, says: “The dollar’s decline may be firmly in place because the Federal Reserve might have the best printing press of them all.” Merk says that despite Fed tapering, the US central bank’s balance sheet has continued to grow this year, while the ECB’s balance sheet has declined and the Bank of England’s has plateaued at a high level.

BOND VALUES AT RISK

“Historically speaking, the dollar has typically weakened in a rising-rate environment,” Merk says. “This is due to the fact that foreigners tend to be large holders of US Treasuries, and as rates rise, those Treasuries are at risk of losing value and provide a disincentive for foreigners to hold them.”

More importantly, Merk says that the US economy cannot afford positive real interest rates. “The biggest threat we face might be economic growth, because a stronger economy may warrant higher interest rates in order to contain rising inflationary pressures,” he says. “If interest rates were to be elevated so that the cost of borrowing for the US government would revert back to its historical average, the annual interest expense may rise from the current $220 billion a year to $1.2 trillion a year, thus crowding out government spending.”

The ECB has been mopping up liquidity rather than printing more money, Merk says. European banks have returned unwanted liquidity to the central bank. “At the same time, there is an amazing stimulus where it’s needed the most: The cost of borrowing for weaker eurozone countries has been falling since August 2012,” he says. “This may be the most powerful stimulus the eurozone has, and it’s a stimulus that’s ongoing and intensifying.”

DOLLAR VULNERABLE

One of the dollar’s greatest vulnerabilities may well be the current-account deficit, Merk says. “In plain English, the current-account deficit is the amount needed to come into the US in order to keep the dollar from falling,” he says. “Even with recent improvements in the current-account deficit, the US still needs to attract over $1 billion every day to keep the currency from falling.”

Because the dollar relies on inflows of money from abroad, if bond markets act up, the dollar might come under more pressure than the euro has ever seen, Merk says. This would force policymakers to impose reforms, he says.

Because the dollar relies on inflows of money from abroad, if bond markets act up, the dollar might come under more pressure than the euro has ever seen, Merk says. This would force policymakers to impose reforms, he says.

Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, says: “The details of the [February] US employment data are weaker than the headline, but the real takeaway is that the report will not change expectations for the Fed to continue to taper, or change when the market expects the Fed to actually raise rates. This is not [likely] until the second half of next year.”

The 175,000 rise in the nonfarm payrolls was above expectations, and the previous two months were revised to show another 25,000 jobs. “The weakness of the report lies in the fact that the unemployment rate ticked up to 6.7%, even though the participation rate was unchanged at 63%.”

The other, and more important, element of weakness is the fall in the workweek, which slipped to 34.2 hours from 34.3 hours in January, Chandler says. January was revised down from 34.4 hours. “This is worth several hundred thousand full-time equivalents, and is likely due to the weather.”

YUAN WOBBLES

China’s central bank taught the investment world a lesson in February, according to Crystal Zhao, fixed income analyst at HSBC Global Research in Hong Kong. The appreciation of the renminbi will no longer be a one-way call, Zhao says. The offshore renminbi in Hong Kong lost 1.4% in February, the worst month since September 2011, when the European crisis entered a more dangerous phase as Greece and Italy became the main focus.

“We believe this round of renminbi depreciation was engineered by the authorities to stem strong capital inflows and stamp out currency speculation,” Zhao says. Regulators are likely to resume this policy from time to time until they see evidence that hot-money flows are receding, she says.

Zhao says the gap between renminbi spot rates in Hong Kong and on the mainland is likely to narrow. “Domestic investors are likely to seek safety in the wake of the first coupon default on a high-yield bond,” she explains.

Shanghai Chaori Solar Energy Science and Technology, a solar-cell manufacturer, failed to pay full interest on its bonds in early March. This was seen as an indication that the Chinese government will no longer continue bailing out companies with bad debt.

HSBC prefers high-grade over high-yield offshore renminbi bonds as a defensive play. “History shows that high grades were more resilient during currency corrections,” Zhao says. “Regarding high yield, uncertainty of policy in the property sector could discourage investors from adding new positions,” she says.

The HSBC/Markit Services Purchasing Managers’ Index for China rose to 51.0 in February from 50.7 in January. The government’s official nonmanufacturing PMI showed activity at a three-month high.