|

|

UniCredit Holding, Milan |

The write-offs taken in early March by UniCredit may fall well short of what Italys largest bank needs to do to satisfy the European Central Bank before it takes over supervision of UniCredit and other EU members banks in November, notwithstanding the considerable investor applause the banks goodwill impairments and resulting loan-loss provisions generated. And UniCredit is hardly the only European bank that may need to take more significant action.

Investors sent the shares of UniCredit up 6% on March 11 after the announcement of the write-downs, which saw the bank set aside 9.3 billion euros (or $13.0 billion) for loan losses. The write-downs reflected loans gone bad, many of them a result of UniCredits acquisitions of other Italian banks. In effect, the bank finally admitted to overpaying for those deals.

Investors nonetheless interpreted the move as welcome if belated recognition by management that the bank will stop throwing good money after bad by continuing to lend to borrowers that cannot make their payments on time. Still, the fact that UniCredit, like other big European banks, may need to do a lot more to satisfy the ECB is likely to weigh on its shares.

In fact,

a study released in January

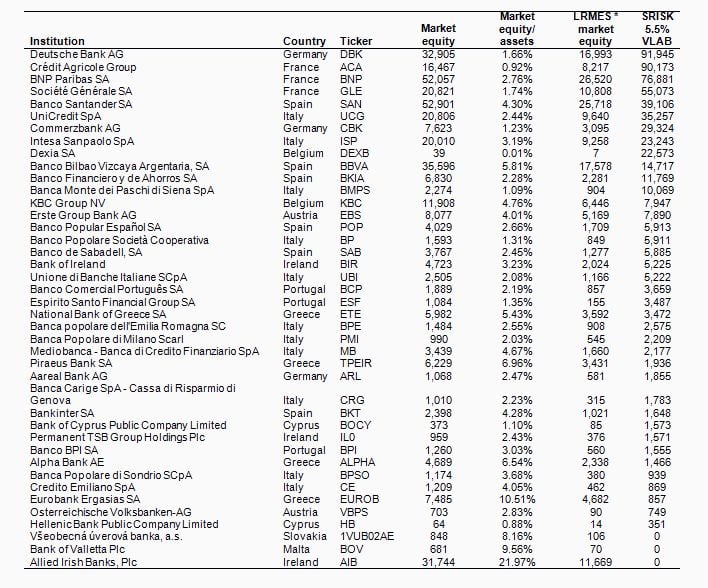

shows that more than 100 European banks may have to raise more than 767 billion euros ($1 trillion) in capital to satisfy their new regulators that they have enough to withstand another financial crisis. The study shows that they are seriously undercapitalized even under current circumstances.

In an interview last Wednesday, the authors of the study, Viral Acharya, an economics professor at New York University, and Sascha Steffen, an assistant professor at Berlin’s ESMT European School of Management and Technology, said they expect more write-downs by UniCredit and other big European banks unless they raise more equity, as a result of the asset quality review (or AQR) now being undertaken by the ECB. Archarya serves as an advisor to the European Systemic Risk Board, a body set up by the European Union to help oversee its financial system.

In their paper, Acharya and Steffen estimated that UniCredit would need 35.3 billion euros or $49.2 billion if the equity market fell 40% during a six-month period and regulators required banks to have capital equal to a minimum of 5.5% of the value of their assets. Of course, that was before the write-downs in early March. Yet Acharya says UniCredits potential shortfall has actually increased since January and now stands at 43.7 billion euros because its debt and market volatility have risen.

But Deutsche Bank, Credit Agricole, BNP Paribas, Societe Generale and Banco Santander would likely need even more capital than UniCredit, if only because they rely more heavily on debt than equity in their capital structure (see table, below).

Much, of course, depends on how tough the ECB proposes to be in its stress tests. Acharya noted that the Federal Reserve has used an even more drastic scenario in stress testing U.S. banks than he and Steffen did, and in contrast to both their research and the Feds stress tests, the ECB has done little in the past to evaluate the quality of European banks’ assets when determining their capital needs.

Acharya expects the ECB to look more closely at asset quality during its next stress tests, however, in order to avoid the need for taxpayer-financed bailouts.And he pointed to UniCredit’s decision to write down bad assets instead of continuing to extend financing to poor quality borrowers as an indication of that.

“What they’ve done probably helps them in the asset quality review,” Acharya noted.

In the past, he said, “Management might have been reluctant to recognize losses, even though it would have benefited shareholders.”

From that perspective, Acharya observed, “AQR has already done a good service.” And he said that could help UniCredit as well as other banks get back to lending to businesses. Like other Italian banks, Acharya noted, UniCredit has invested heavily in government bonds and “small to medium sized companies have been really strapped for financing as a result.”

The lack of bank financing has led to many small Italian firms listing their shares instead, which he pointed out “is not a great sign for growth prospects.”

“We fundamentally think the Italian banks, and also Spanish, German and French banks, are not as well capitalized as they should be,” Acharya added. Still, he pointed out that Italian banks would face the biggest shortfall if their bad loans are taken into account. “If you mark down their bad loans,” he said, “Italian banks are going to need the most capital.”

Public Banks Sorted By Systemic Expected Capital Shortfall

|

|

|