OUT OF THE SHADOWS

By Arthur Clennam

The instability of Chinas banking system is underscored by its structured-trust-product nightmare.

Since the onset of 2014, old lions such as investor George Soros have characterized Chinas banking woes as the most severe threat to the global economy. The China Cassandras fear that Chinas government is frozen by the magnitude of the problems it faces and may stall on reforming the banks, a key component of structural reform aimed at changing Chinas investment-driven growth model to one sustained by consumption.

Fear of a lack of government resolve in China can be linked to the sell-off in emerging markets stocks in late January. Continued tapering by the US Fed was also a trigger, but two fears about China were in the mix. The first is that reform will lead to tighter credit conditions and further slow Chinese growth. The second is the concern that the government lacks the grit to tackle Chinas debt explosion and therefore will be unable to carry out its broad reform agenda to restructure the economy.

An early attempt by the current governmentwhich officially came to power last Marchled to backpedalling: Last May, it allowed interbank lending rates to spike by holding back the funding it typically injects to reassure counterparties in the financial system. Banks responded by tightening lending, but the knock-on effect caused too sharp a slowing in the economy. The government quietly instituted a mini-stimulus that led to a pickup in growth. Financial reform was top of the governments agenda at the keystone government policy meeting known as the Third Plenum in November.

In December, the May bank-crunch scenario was largely repeated, as interbank short-term lending rates soared, leading to fears of a drying up of liquidity in the system. The government injected liquidity into the interbank market once again. The repeat performance prompted this comment from Soros, writing in an annual economic forecast in early January: There is an unresolved contradiction in Chinas current policies: Restarting the furnaces also reignites debt growth, which cannot be sustained for much longer than a couple of years.

Alberto Forchielli, who runs the China operations of hedge fund Mandarin Capital, sees an even tighter time frame. Basically, Chinas banks have the same level of bad debt they had in 2003, he says. Thats estimated at 13% of assetswhich means theyve blown out their equity.

Thats why Chinas banks are the only banks in the world whose market values are below book, Forchielli adds. Theyre selling damn cheap. Even the worst bank in the world sells at two times book. And Im not even including shadow-banking assets. If you include shadow lending, Chinas financial system is broke.

SHADOW-BANKING HAZARD

Getting rid of moral hazardan incentive that encourages risky bettors to bet againmay be hazardous to a governments health. This seems to be the position of the still-undeclared parties in Chinas ruling elite that approved the bailout of a Rmb3 billion ($496 million) shadow-banking entity called Credit Equals Gold No. 1, a failed trust product, five days before a crucial payment deadline on January 31.

The case had become proxy for a much larger issue: Is Chinas government serious about tackling the huge debt problem hobbling its banking system? China Credit Trust Cothe fourth-largest trust company in China and majority state-ownedpackaged the Credit Equals Gold No. 1 product and distributed it through Industrial & Commercial Bank of China (ICBC) to raise funds for Shanxi Zhenfu Energy Group, a coal mining firm in Shanxi Province that subsequently collapsed in 2012.

|

|

|

Such trust products are known as shadow-banking vehicles. Though they are distributed through the nations state-owned and privately owned commercial banks, they do not appear as liabilities on these banks balance sheets. Trust companies like China Credit package them, and respectable banks like ICBC market them.

ICBCs original stance after Credit Equals Gold No. 1s default was that it would not recoup its investors. But on January 26, the bank told investors that they could sell the rights in the product to an unidentified buyer at a price equal to the value of the principal.

Separately, China Credit Trust said it had agreed to sell the shares it had bought in Shanxi Zhenfu to an unnamed third party.

Investors received a small haircut: They were told they would not receive interest on the third and final year of the product, equivalent to about Rmb300 million. To date, neither ICBC nor China Credit Trust has identified where the bailout funds came from.

The alternative could have triggered knock-on effects difficult to dimension, wrote credit rating firm Moodys, creating a new verb to describe the potential mess if a principal default of the fund were allowed.

The eleventh-hour bailout almost certainly came from very high up in Chinas government. It probably came from the prime ministers office but well never know for sure, according to Forchielli. He calls the decision a tragic mistake. It creates tremendous moral hazard, saying to investors, to the market, we are going to honor shadow-banking debt.

The probable high-level nature of the decision indicates the governments sensitivity to potential panic as it grapples with the nations fragile shadow-banking market. Assets managed by Chinas 67 trust companies reached Rmb9.6 trillion ($1.7 trillion) as of the end of September 2013, according to the China Trustee Association. Other estimates of the shadow-banking debt put the total figure much higher.

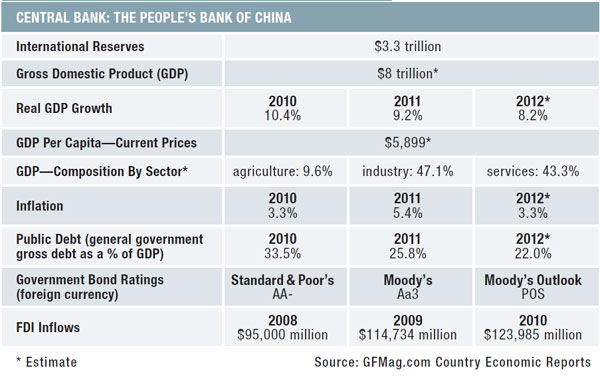

Both public and private debt have been proliferating: Charlene Chu, former senior director of Fitch Ratings Beijing, said last May that total FI lending in China was 198% of the nations GDP in 2012, up from 125% four years earlier. and the government reported in January that the local government debt had grown 67% in only three years to $3 trillion.

More is at stake than the shadow-banking problem. Christopher Wood, chief equity strategist at CLSA Equity Markets, writing in his Greed & Fear weekly note, warned that any comprehensive government attempt to organize a rescue of shadow-banking investors in the event of widespread defaults would signal that the governments talk of pursuing reform isnt genuine. The Credit Equals Gold case added heft to his argument. The China Credit Trust product stemmed from a loan to an unlisted coal company and was apparently owned by about 700 wealthy investors with average holdings each worth over Rmb4 million. This was hardly a bailout to protect widows and orphans.