THE COST OF INSTABILITY

By Justin Keay

The full effects of recent upheavals and unrest in Turkey have not yet been felt, and policymakers have some serious work ahead to bring markets back in order and reassure investors of the country’s economic and political steadiness.

For those who thought Turkey was evolving effortlessly into the world’s first true Islamic democracy, the past few months have been a rude wake-up call. First there were the Taksim Square demonstrations that spread across Turkey and seem likely to recur once the heat of summer is past.

These have revealed the gaping chasm between secular, white Turks and the green, pious Turks of the Anatolian heartland who are prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoan’s most loyal supporters. They also revealed Erdoan’s Putin-like intolerance of dissent and the extent to which he is prepared to blame “foreign provocateurs” for the unrest. The subsequent purge of journalists who covered events in ways not to the government’s liking provoked further parallels with Putin: More than 50 were sacked or forced to resign.

Meanwhile the final outcome, on August 6, of the long and protracted trial of senior military and establishment figures from the Ergenekon conspiracy (coup attempt) also suggests government interference. Just 21 of the 275 accused saw their cases dismissed, the remainder getting heavy sentences—in some cases life imprisonment, including former army chief lker Babu—for an alleged plot last year to overthrow the government.

There has been more. Infuriated by pressure on the lira, Erdoan and his supporters have blamed the “international interest rate lobby,” encouraging the banking commission to launch an investigation into the local foreign exchange market. Erdoan has also criticized the expansion of bank debit and credit cards in Turkey (some 152 million are now in circulation, up 12 million on a year ago) blaming them for encouraging indebtedness. And a major tax investigation is being launched into Koç Holding, perhaps Turkey’s largest industrial conglomerate, with tax inspectors raiding the offices of its refinery division, Tüpra, in July in the latest example of nascent green Turkey taking on the country’s old white establishment.

One cannot help getting the impression that Erdoan is attempting to take on any element of the free market that is unappealing to him, sidelining ministers with a more realistic view of how the global economy works. Unsurprisingly, many of the government’s former supporters in the business community have lost confidence in it. The big question for Turkey—aside of course, from what sort of country it will eventually evolve into—is whether it can afford all this. With the Turkish lira down some 9% or 10% since the protests started and the stock market 21% off its May peak, Western analysts think not.

THE PRICETAG

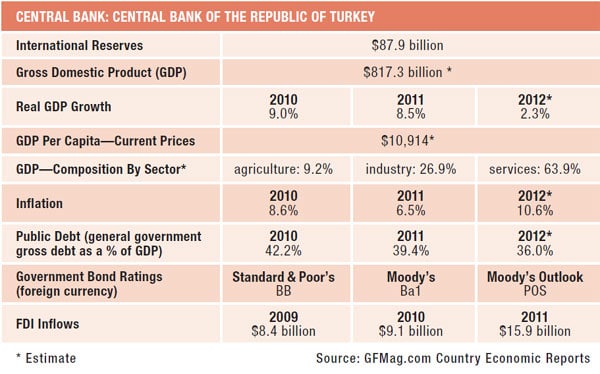

“Given the structural nature of its large current-account deficit (which between January and May reached $31.9 billion, almost $6 billion up on the same period in 2012) and the fact it remains dependent on short-term external financing, Turkey cannot continue like this,” argues Naz Masraff, Turkey analyst at US consultancy the Eurasia Group. She says that the central bank has sufficient funds to cover the deficit this year—despite selling over $6 billion of foreign exchange in July in a vain attempt to protect the lira. However, sooner or later, Turkey’s dependence on wholesale markets will make itself apparent, compounded by the domestic savings ratio’s remaining around 14%—low compared with that of other emerging markets.

Taking on Koç seems particularly foolhardy—given that it accounts for 9% of the country’s GDP, 10% of its exports and 16% of the stock market. Aside from Tüpra, subsidiaries include Yapi Kredi Bank and white goods manufacturer Arçelik, and Western partners include UniCredit, Ford and Fiat.

Despite government and central bank efforts to prevent the inevitable, rates for overnight lending increased 75 basis points to 7.25% in late July, and another 50bps in early August, to 7.75%. Further increases are probable, given strong external pressures on the lira. Capital Economics suggests the central bank may be forced to raise rates by as much as 500 basis points, affecting one-week repo and interbank rates. “Turkey’s deficit leaves it vulnerable in the event of a fresh deterioration in investor sentiment,” says Neil Shearing, chief emerging markets economist at Capital Economics, who argues that recent events have undermined the business environment and economic management.

Some observers fear Turkey’s generally stable and prudent bank sector may also face difficulties. The sector is likely to be affected by rising interest rates in the short term, but medium and long-term pressures are also building. New international and domestic rules regarding capital, leverage and risk weights, among other new regulations, will increase capital costs and hit revenues.

The sheer pace of credit growth in recent years—private-sector credit as a share of GDP has risen 40% in the past decade—and the extent to which external wholesale markets have played a role may put pressure on some financial institutions.

“Macro-imbalances are casting quite a long shadow,” says Shearing, who says the credit expansion of the last decade is of the same magnitude that has preceded other emerging-markets crises. “We expect a new wave of consolidation in the sector, as profitability decreases and volume becomes even more important to maintain profitability,” says Hüseyin Özkaya of Odeabank in Turkey.

Officials are already admitting the official targets of 4% GDP growth and $158 billion in exports this year may not be reached, although deputy PM Ali Babacan blames this on international economic fluctuations.

In the short term at least, the slide in the lira coupled with the increase in the risk premium in the wake of the early summer unrest will increase Turkey’s funding costs and pile pressure onto banks. However, the sector will doubtless adjust: There is huge, untapped potential in retail banking, SMEs and trade finance—not to mention in funding Ankara’s ambitious infrastructure plans. Aliveren also argues that banks are well placed to expand further into the Middle East. He expects new foreign banks to enter the market following the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency of Turkey’s (BRSA’s) decision to ease restrictions on new entrants, especially given the contraction in opportunities in developed markets.

Overall, Turkey’s economic problems must be seen in perspective. Even with growth lower than expected, Turkey is still one of the world’s fast-growing emerging markets, and long-term confidence remains high, given the young population, proximity to major markets and private-sector dynamism. This has been reflected in the real estate market: House prices over the past year have risen by 12%. Commercial and retail property is also doing nicely, the latter being boosted by Turks’ insatiable demand for shopping malls: Some 2.75 million square meters of shopping space is to be constructed in 73 shopping centers by the end of 2015. Unsurprisingly, construction looks set to remain one of the most resilient areas of the economy, despite the recent interest-rate rise.

The government must keep its focus on attracting investment, however, not least to help fund its ambitious infrastructure plans—including a third Istanbul airport, a new Bosphorus bridge and numerous highway, rail and port projects, as well as a bid for the 2020 Summer Olympics. Energy sector requirements alone require considerable funding.

“Two-thirds of the deficit reflects energy imports, and demand for energy can only grow further,” argues Masraff. She says that, with demand for power increasing 7% a year, Turkey needs to double generation capacity from the current 58,000 MW over the next 10 years, at a cost of $100 billion. Plans are afoot to construct three new nuclear power plants and at least three new LNG plants. The country also hopes to buy gas from northern Iraq—where many of its companies are already active—and from Israel, currently developing its own considerable offshore reserves.

For the country as a whole, analysts say that sooner or later the government will have to adopt a more ameliorative approach, even if it does so only after next year’s local and parliamentary elections and 2015’s presidential ones, when the need for populist rhetoric is past. “I am confident Ankara will come to terms with its need for FDI and foreign investment to drive growth, and pragmatism will once again be the order of the day,” says Masraff.

INVESTORS KEEN ON TURKEY, DESPITE TAKSIM SQUARE

To really get to know what’s going on somewhere in Turkey—behind the headlines and official pronouncements—it’s probably best to ask a lawyer. Certainly, unlike senior officials, who shy away from questions about the impact of July’s demonstrations on Turkey’s appeal for investors, Mehmet Gün, of law firm Mehmet Gün & Partners, is quite open. He believes that in many ways the demonstrations actually strengthened the country’s appeal.

“Although the TV images looked quite dramatic, Taksim Square isn’t Tahrir Square: Turks know who they are and what kind of society they want. Most of the demonstrators were educated, professional young people whose main demand was for a more sophisticated management of the country, with less interference from top, something that can only be good,” he says.

Gün believes that despite Erdoan’s bellicose response, senior AKP Party figures have taken lessons from the unrest. He also believes Erdoan will heed opinion polls, which suggest 85% of voters don’t want him to run for the presidency next year or see Turkey become a presidential rather than a parliamentary republic.

Gün believes that despite Erdoan’s bellicose response, senior AKP Party figures have taken lessons from the unrest. He also believes Erdoan will heed opinion polls, which suggest 85% of voters don’t want him to run for the presidency next year or see Turkey become a presidential rather than a parliamentary republic.

“Investor interest in Turkey is stronger than it has ever been,” he says, pointing out that his firm—which is involved in everything from business start-ups and advising foreign companies about setting up in Turkey to intellectual property law and commercial dispute resolution—has never been busier.

He says there is foreign investor interest across the spectrum—with the IT, energy, automotive and food and beverage sectors of particular appeal. Real estate, tourism and healthcare are also of interest, with the latter boosted by reforms that have included the introduction of universal healthcare five years ago. Hedge funds have been active, taking over underperforming small and medium-size businesses and profitably turning them around. Geographically, most interest is in western Turkey, but Gün says there is also strong construction and real estate interest in less-developed eastern Turkey, where wages are lower and potential opportunities even greater.

Gün believes what is driving foreign investment is the fact that returns are high—much higher, certainly, than in stagnant Europe—and the general perception that despite the recent unrest, Turkey is a country demonstrably moving forward. He says the business and investment environment is improving all the time. “OK, there are problems, but this country tends to be quick to identify and rectify them.”

Financial Hub

Going forward, he reckons the growth area to watch is finance, reflecting the government’s desire to transform Istanbul into a financial hub rivaling London, Frankfurt and Dubai. Work is already proceeding apace on the Istanbul International Financial Center (IIFC). Numerous firms from the Gulf, the Maghreb region, central Asia and the Balkans—all areas with which Turkey has close historical, trade and other ties—have already expressed the desire to move into the 170-acre area over the next few years. Currently, it is estimated that the project will cost $2.6 billion, involve the construction of new infrastructure, including a metro station, and be completed by 2017.

Insurance, reinsurance, banking and other services have been prioritized, with foreign banks likely to be present in growing numbers: Japan’s largest bank, Bank of Tokyo-Mitsubishi UFJ, has become the latest to set up shop in the city, with more expected ahead of the opening of the IIFC.

Plans are also ongoing to create an international arbitration center reflecting the increasing use of arbitration as a conflict resolution mechanism in Turkey. The authorities have recognized that the widespread use of arbitration to resolve disputes—rather than the slower and more costly alternative of going through the judiciary—is one of the key reasons behind the commercial success of cities such as London, Geneva and New York.

The arbitration center is expected to open next year within the IIFC and to comprise two courts, one to resolve domestic, and the other international, disputes. “The Center will show that Istanbul is serious about its financial ambitions and knows what must be done to realize them,” says Gün.

ESSENTIAL CONDITIONS FOR FOREIGN DIRECT INVESTMENT

One of the hallmarks of the old, pre-AKP Turkey was a poor performance in attracting FDI, with companies scared off by the lack of transparency, a weak, inflation-prone economy and governments that just didn’t seem to care. Ten years on, the picture is very different: Although the $12.4 billion Turkey attracted last year is underwhelming, given the country’s huge potential, no one doubts Ankara’s determination to encourage as much foreign investment as it can.

|

|

Ayci, Ispat: The government has established the Investment Advisory Council to address administrative barriers, improve the image of Turkey and provide a global perspective to the ongoing investment agenda |

Deputy premier Ali Babacan has drawn attention to the 417 billion Turkish liras ($208.6 billion) of fixed investment that Turkey needs over the next five years as part of its 10-year strategy to become one of the world’s top 10 economies with a GDP of $2 trillion. Especially given Turkey’s low domestic savings ratio, much of this capital will have to come from abroad, ideally in the form of FDI.

Indeed, many of the large infrastructure projects already undertaken have been foreign-funded—including the Marmaray rail and mass transit project in Istanbul and two Bosphorus bridges—while Ankara has also been turning to international financial institutions to support much-needed projects.

Last year Turkey became the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development’s second-largest country of operations, after Russia, with €1 billion ($1.3 billion) in new investments in 2012 alone. Since beginning operations in Turkey in 2009, the EBRD has invested more than €3 billion in direct deals and through credit lines. It recently supported Turkey’s first-ever infrastructure bond—launched by Mersin International Port for $450 million—investing $79.5 million into a project that will see Turkey’s largest multipurpose port expanded and modernized.

The country also has highly ambitious plans for construction, with almost one-third of dwellings to be replaced by earthquake-proof housing and some $400 billion needed for urban renewal projects. Little wonder that Turkey was identified last year as the third-most-attractive emerging-markets real estate market by the Association of Foreign Investors in Real Estate.

For their part, the authorities have transformed beyond recognition what was once a murky business climate. In a report released this May, the WTO said Turkey now has all the essential conditions for attracting large-scale FDI: commercial opportunities, a conducive investment environment, the rule of law and the predictable, stable environment needed by investors in for the long term. Little wonder that Ernst & Young’s investor attractiveness survey—completed in May, before subsequent events in Taksim Square—found that 71% of the 200 top global business leaders it interviewed felt Turkey’s attractiveness had improved over the past three years, with a similar percentage expecting further improvements.

lker Ayci, head of Ispat, Turkey’s official investment agency, points to the continual efforts being made to further improve the investment environment. “In addition to a Coordination Council for the Improvement of the Investment Environment, the government has established the Investment Advisory Council, with the participation of prominent multinational companies, to address administrative barriers, improve the image of Turkey and provide a global perspective to the ongoing investment agenda,” he says.

The big challenge for Turkey in the wake of the recent unrest, declining investor appetite for emerging markets and a generally tougher economic outlook, is to keep this all on track.