CHANGE IS AFOOT

By Paul Mackintosh

Central & Eastern European countries are trying hard to differentiate themselves from their southwestern neighbors. Corporates in the region are dealing with a new playing field as many assets once owned by major Western players are changing hands.

Central and Eastern Europe has been drawn into a very different world by its eurozone neighbors following the global financial crisis, even though its own member economies have not had the structural issues of Greece, Portugal or Cyprus. And as with the economies of countries in the region, the fortunes of CEE companies are diverging, as companies see a changing of the guard, with some overburdened Western entrants from the first waves of ambitious eastward expansion giving up their positions to other players—often because of structural difficulties outside the region.

Christoph Klingen, deputy chief, emerging economies unit at the IMF European department, notes in the European Investment Bank’s January 2013 report, “Banking in Central and Eastern Europe and Turkey,” that Central, Eastern and Southeastern Europe (CESEE) has held up well against the challenges posed by the euro area crisis. “Nonetheless,” Kingen adds in the report, “the crisis has left unpleasant legacies,” including large nonperforming loan books and budget pressures at the region’s banks.

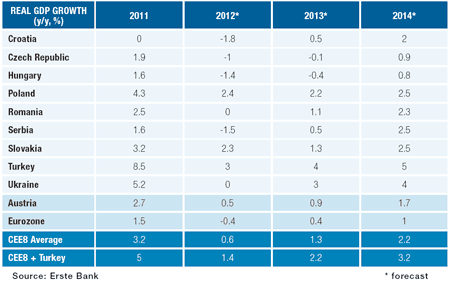

Also, economies in the East are diverging. Poland and Slovakia remain relatively strong, with 2012 GDP growth of 2.4% and 2.3%, respectively, forecast to ease to 2.2% and 1.3% in 2013, according to Erste Bank. GDP in Croatia, the Czech Republic and Hungary, in contrast, shrank 1.8%, 1% and 1.4% in 2012.

CEE nations overall are being handicapped by reduced demand and capital supply from the West. The latest medium-term forecast from the Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (WIIW) notes that Central, Eastern and Southeastern European countries are, by and large, “small, open economies held hostage to the excessive fiscal austerity pursued in the euro area.” Nonetheless, “the crucial factor behind the disappointing CESEE growth performance has been the weakness of domestic demand,” a result of unemployment, stagnant wages, austerity and household deleveraging, adds the institute.

UTILITIES WITHDRAW

On the corporate side, utilities, many of which were scooped up by Western operators during earlier privatization rounds, have represented significant trouble spots. Bulgaria’s government fell in February, partly over public outcry about high utility bills. At the end of March, German utility RWE announced the sale of its entire stake in Czech gas transmission operator NET4GAS for €1.6 billion ($2.1 billion) to a consortium of Allianz and Borealis Infrastructure, having already sold its 44.2% stake in Hungarian gas distributor Tigáz to its Italian operating partner, Eni. Peter Terium, RWE’s CEO, called this “a further milestone in our divestment program to reinforce our capital base and our financial strength.” In Bulgaria, Austrian power utility EVN has just announced litigation to protect its own investments there.

“The eurozone crisis has “left unpleasant legacies” in CEE banking.”

– Christoph Klingen, IMF

In some cases, the withdrawals of Western owners has opened the door to BRIC market players. China gained its largest CEE investment to date in February 2011 with the purchase of Hungarian isocyanate producer BorsodChem. It was picked up by China’s Wanhua Industrial Group for €1.2 billion from a private equity consortium led by European PE firm Permira, which had been unable, in the wake of the global financial crisis, to sustain the leverage repayments on its 2006 €1.6 billion LBO deal. Russian companies have also made inroads in utilities and the banking sector (see sidebar).

Concerns persist over both domestic corruption in certain CEE markets and the tactics that some foreign acquirers have used in their rush to exploit CEE opportunities. In Sweden a civil suit against telecoms firm Ericsson by its former general manager in Romania over $7 million allegedly diverted from company coffers (Ericsson claims its Romanian general manager pilfered the funds; the GM claims the funds went to a company-approved slush fund to pay off Romanian officials) has exposed a network of shell companies and disguised payments allegedly used to bribe local decision-makers in the early 2000s. Similar allegations have dogged the telecom TeliaSonera, Saab and British defense contractor BAE. More recently, Croatia’s former prime minister Ivo Sanader was convicted in November 2012 on corruption charges related to Hungarian petrochemicals company MOL’s 2009 acquisition of Croatian rival INA.

NEW DEALS

CEE countries, especially those that are strongest economically, are trying to capture what appetite there is for deals. At the end of March, Italian insurer Generali paid €1.3 billion for a majority position in its joint venture with Czech insurer PPH, while selling the latter its consumer finance assets in Russia and the CIS. Poland has an ambitious privatization program of up to 160 companies slated for 2013, including chemicals company Ciech, leading bank PKO and gas utility PGNiG, as well as struggling national air carrier LOT. But the attempt to privatize state-owned Polish real estate holding group Polski Holding Nieruchomosci in early February misfired when the flotation of a 25% stake netted just €57 million in an IPO pushed to the bottom of its indicative range.

CEE M&A activity in general, already down from €150 billion in 2011 to €121 billion in 2012, according to CMS/DealWatch, will be limited in 2013 as the credit supply remains constrained. Continuing eurozone turmoil has been blamed for depressing M&A volumes worldwide, taking first-quarter investment banking deal fees from the region to their lowest level since 2003, according to Thomson Reuters. “Even under the most optimistic scenario, in the medium and long term the CESEE countries will be generally unable to replicate the growth rates observed prior to the 2008–2009 crisis,” warns the WIIW.

|

| Photo Credits: KAROL KOZLOWSKI / SHUTTERSTOCK.COM |

The key strategic priority for CEE economies is how to position themselves as Western Europe deals with its imbalances—a relatively prosperous north and an uncompetitive, debt-burdened south. In the run-up to Poland’s referendum on joining the eurozone, Foreign Affairs minister Radoslaw Sikorski has already brought up past comments associating Poland with Northern Europe. And Croatia, Slovenia and conceivably Hungary may slide into the southern camp occupied by Greece, Cyprus, Portugal, Italy and Spain. Countries and corporates alike may see a new roster of winners and losers.

CEE BANKING: OVER-COMING THE LEGACY OF THE FINANCIAL CRISIS

CEE banks were attractive M&A targets in the early and mid-2000s. Since the crisis, the structural problems of Western lenders have combined with changing prospects in their focus markets to trigger ownership changes in the region. According to Werner Hoyer, president of the European Investment Bank (EIB), many CEE lenders remain “largely dependent on funding from Western parent banks which themselves face increased capital needs, as well as funding pressures and regulation.” And, he adds, “excessive credit growth largely financed from abroad made CEE economies particularly vulnerable” after 2008. Some owners are severely challenged by the crisis; others are capitalizing on it.

The differing fortunes of Austrian banks illustrate CEE banking’s separation into post-crisis winners and losers. In February 2012, Austria’s Volksbank International sold its entire CEE chain, barring its business in Romania, to Russia’s Sberbank for €515 million ($672 billlion)—to reduce total risk-weighted assets by €6.6 billion. One year later, Sberbank CEO German Gref announced publicly that his group may take action against Volksbank and its auditors over its CEE asset quality. Austrian peer Raiffeisen may, reportedly, pick up the Romanian business and consumer networks of Citibank, which, in December 2012, announced plans to sell these amid a strategic decision to focus on growth markets.

Moody’s Investors’ Service recently issued a negative banking system outlook on Austrian banks, citing their exposure to bad CEE debt as a key weakness. “Aggregate system problem loans reached 10.2% of total loans at year-end 2011, reflecting many banks’ large CEE activities,” remarked Swen Metzler and Carola Schuler in the report. The three largest Austrian banks in particular—Erste, Raiffeisen Bank International and UniCredit Bank Austria—are exposed to a possible renewed downturn in several CEE countries, the report concluded.

Political factors are exacerbating these problems. Enrico Cucchiani, CEO of Intesa Sanpaolo, Italy’s largest lender, called conditions in Hungary a “nightmare” in a recent earnings call, highlighting €279 million of losses at the bank’s CIB Hungarian unit, and warned that it might exit the market entirely. Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán has said repeatedly that he wants to see at least 50% local ownership of Hungarian banking assets.

Overall, CEE banking may emerge structurally stronger from the crisis, but only after difficult and taxing adjustments. The EIB report concludes that Western entrants to CEE banking are developing more sustainable platforms, “increasingly financed by domestic funds,” but growth remains slow.