TIME FOR CHANGE

By Antonio Guerrero

Nigeria holds great promise with its massive oil reserves, but endemic corruption, unfettered militant attacks on pipelines and lack of regulatory clarity could halt progress in its tracks.

When the Nigerian government three years ago signed an amnesty agreement with militants who had been wreaking havoc on oil operations along the Niger Delta, authorities and oil companies believed it was time to get back to business. While violence has declined, former rebels have found a new revenue source that is reducing output in Africa’s largest oil producer and creating a parallel economy.

Thieves are tapping the Trans Niger oil pipeline and selling crude to informal refiners. Shell Oil estimates 150,000 barrels per day of crude are stolen. Finance minister Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala says as much as one-fifth of government revenue is lost to oil theft. Environmental damage is also substantial, and the UN Environment Program estimates it would take 30 years and $1 billion to clean up the Niger Delta’s Ogoniland region.

|

|

Ottoo, Pace: Nigeria must not be complacent; it will not last long as an oil investor darling |

“Oil and gas exports account for 77% of all government revenue. Thefts and militant activity pose a risk to future investment in the affected areas,” says Robert Hamill, a partner at law firm Mayer Brown and co-leader of its global energy industry group. “The government’s policies aim to deter further theft and violence but also to address some of the underlying disenfranchisement issues.”

Overall oil production has been declining steadily, reaching an average daily output of 2.35 million barrels per day during the first quarter of 2012, down from 2.51 million bpd during the same period last year. With inadequate refining capacity, the country is also forced to import refined fuel. The government budgeted $5.5 billion for fuel subsidies this year alone. When it attempted to remove subsidies in January, the administration reintroduced them after a week-long strike and violent street protests. Ironically Nigeria, one of the world’s major oil producers, may soon face a fuel shortage. The government under president Goodluck Jonathan is running out of funds to pay suppliers and cover subsidies.

Despite the drawbacks, analysts say that major oil companies are unlikely to exit the market, although some have made noises suggesting they are considering it. “Government should move rapidly with proposals for the reform of the oil sector, implement the privatization program and reinforce transparency and accountability of the oil sector,” says Aderanti Adepoju, chief executive at the Human Resources Development Center in Lagos and coordinator of the Network of Migration Research on Africa. The Jonathan administration has been pushing the Petroleum Industry Bill (PIB), a comprehensive program to reform the sector’s regulatory framework, but the National Assembly in the capital of Abuja has been slow to pass it.

|

|

Adepoju, HRDC: Nigeria should move rapidly to enact oil-sector reform proposals |

Iain Donald, director of global risk analysis, Americas, at consultancy Control Risks, agrees: “Lack of long-term clarity in the legislative framework and operating terms of Nigeria’s upstream oil sector has caused many of the biggest operators to place large-scale investment projects on hold until the PIB is passed.”

Adepoju adds: “Many foreign oil companies are colluding with local officials to underreport their output, avoid paying appropriate tax and avoid corporate social responsibility,” he contends. “Government must promote an environment devoid of violence and insecurity for oil companies to conduct their lawful operations and attract long-term investment, but also promptly punish noncomplying companies.”

Nigeria faces stiff competition on the horizon, according to Richard Ebil Ottoo, assistant finance professor at Pace University’s Lubin School of Business in New York. “The country’s attraction lies in its existing and proven commercial oil reserves, far more appealing than the usual uncertainties surrounding new explorations,” he says. “Yet, Nigeria should not remain complacent. It will not last as the center of attention in Africa for oil investors for long. The eastern part of the continent—comprising Southern Sudan, Somalia, Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi and Mozambique—will likely provide the largest amounts of oil and gas reserves in the coming years.”

INVESTMENT DESTINATION

Foreign investors continue to seek opportunities in Nigeria, even beyond the oil sector. The country received more than $116 billion in foreign direct investment over the past decade, according to Ernst & Young, making it the largest FDI recipient in Africa. Of total FDI, 80% went to oil and gas. The report warns that weak infrastructure and endemic corruption, coupled with political risk factors, could limit growth. The finance ministry recently cut its 2012 GDP growth forecast to between 6% and 7%, from a previous outlook of between 7% and 8%.

NEED FOR DIVERSITY

|

|

Hamill, Mayer |

With a $415 billion GDP, Nigeria’s economy is the world’s 31st-largest, but the government hopes to make it one the world’s 20 largest economies—surpassing South Africa as the continent’s largest economy—by 2020. To do so, it will need to tackle important issues, including a large unbanked population. Fewer than 20% of Nigerians hold bank accounts, and fewer than two million have insurance policies. Banks are also accused of ignoring SMEs and individuals to focus on larger corporate clients, creating a financing void for the majority of the population.

The government must also attract investment into nontraditional sectors. “Nigeria presents promising investment opportunities to foreign investors, extending well beyond the oil and gas sector,” says Control Risks’ Donald. “Sectors such as power, agriculture, solid minerals, manufacturing, aviation, housing and construction are all areas of focus for the present government, as it attempts to create jobs, diversify the economy and reduce Nigeria’s dependence on oil.”

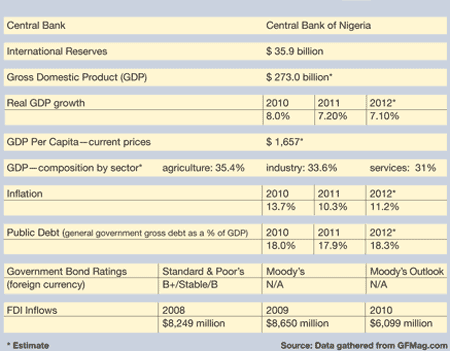

GFmag.com Data Summary: Nigeria