NO HAND AT THE HELM

By Paula Green

As part of its Salon series, Global Finance sat down on January 11 with Ian Bremmer, president and founder of political risk analysis firm Eurasia Group, to discuss increasing geopolitical upheaval and how global policymakers may find their way through it.

|

|

Geopolitics and risk in the spotlight at Global Finance’s monthly Salon PHOTO: TANIA VIRA |

Eurasia Group’s Ian Bremmer started the firm more than a decade ago and created Wall Street’s first global political risk index. A Stanford University graduate, he has written several books, including The J Curve: A New Way to Understand Why Nations Rise and Fall , published in 2006.

While much of the media and many analysts remain focused on upcoming elections in the United States, Russia, France and elsewhere, Bremmer has his eye steadily centered on 2013, when the US-China relationship may again take center stage as the key issue dominating global geopolitics. The evolving relationship of the two economic giants is fraught with opportunities and risks, from currency to cybersecurity to economic competitiveness, he notes.

Bremmer says he is sure that the United States will remain an economic powerhouse even as it drops its decades-long role as the driver of the global economy and stability. But without the backing of the US this leaves a worldwide power vacuum that will have long-lasting and far-reaching consequences. What remains to be seen is who will fill the vacuum, and when.

This is G-Zero: In contrast to the G-7 (or the G-1, as the US used to be), Bremmer sees no hand at the helm of the global ship.

There is, at present, no single country that can perform that role, he says, but at some point down the road it must be filled. He believes the US will be a player, but not the only player.

What is unknown is with whom the United States will be sharing power. China is not a given, he says. Chinese officials themselves know that their 10% annual growth rates, powered by a politico-economic model that includes cheap labor, cheap capital and strong state control, is not sustainable over the long term.

|

|

We are in an interregnum in geopolitical development, and it is unclear when a new model will emerge PHOTO: TANIA VIRA |

We are in an interregnum in global geopolitical development, says Bremmer, and it is unclear when a new model will emerge.

Global Finance: Why is the departure of the US military and the possibility of sectarian strife in Iraq a problem for Iran?

Bremmer: Iran is a big risk right now [from a stability perspective] for three reasons: the internal of struggle of its elite; the economic impact of international sanctions and the domestic impact of poor management of its economy; and [the effect of] external geopolitical shifts—such as we are seeing in Bahrain, Syria and Iraq. If [Iraqi president Nouri al-Maliki] can hold the country together, it would be better for Iran as there would be stability. But the very serious strife that seems to be emerging among the Sunnis, the Shias and Kurds will not be good for Iran. And Maliki could end up being mayor of Baghdad [with little or no control beyond city limits].

GF: What relevance, if any, does the Occupy Wall Street movement have for US and global politics?

Bremmer: The Occupy Wall Street Movement shows the social cleavage that is widening within the United States. It does impact issues like crime and consumer sentiment, and it polarizes people. It’s an indication of the country’s growing social stratification, but it will not impact the presidential race. It does not have real geopolitical influence.

GF: How are the interests of corporations being managed by political leaders in the US and globally?

Bremmer: Corporations do not want competition. Chief executive officers want monopolies and subsidies. The government has to act as a referee and set regulations. But in the US corporate interests are entrenched in a political system that lets them throw money at it [which creates a conflict of interest].

|

|

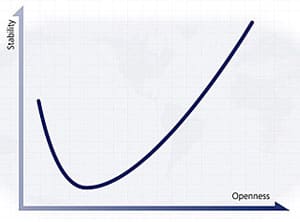

The J Curve |

GF : Does the political will exist in Europe to keep the eurozone together?

Bremmer: I think it will stay together. What will matter over the long term is what the core European states will do to help states that are not competitive. What bears watching is which way these brittle economies, such as Hungary, will go. It could be in either direction—towards more openness or more autocratic rule. It’s interesting to watch the technocrats led by Monti [prime minister Mario Monti] in Italy. There will be a tension between those who want to set broad rules for Europe to make sure everybody stays in line and those who want to go out on their own.

GF: How do you predict political events?

Bremmer: I can analyze political events, but I can’t predict them. I am trained as a political analyst with 125 well-trained analysts and 500 more people on the ground around the world. I think crystal ball gazing is wrong. The predictions made by various banks and institutions for, say the world’s economy in 2050, are reprehensible. You can’t do that. With the J Curve, we don’t predict the next shock, but the countries that are less resistant to the inevitable shocks. There will be more shocks. And that is a problem in a world without real global leadership.

GF: Can you explain your concept of the J Curve model?

Bremmer: At the left side of the J, you have the closed countries, such as Russia and China, that are stable and successful, but not over the long term. On the upper portion of the J, you have the consolidated democracies, such as the United States and Japan, which are successful and are sustainable for the long term. At the bottom of the curve, you have the countries that are brittle and could go either way. The risk in today’s world is that the number of countries, even European countries, in this category, is growing. And we don’t know which way they will go.

GF: Any final thoughts?

Bremmer: At the end of 2008, it was the end of history as we knew it. It was ripped up. It’s going to be more challenging for economies to grow as they compete for resources, and we have news issues like climate change to deal with. We’re in a period of extended volatility that is not sustainable.