FOCUS: INVESTMENT BANKING IN ASIA

By Michael Shari

Asia’s big banks are elbowing out their Western rivals as demand for financial services skyrockets in the region—and beyond.

One of the great ironies lost in the panic of the global financial crisis of 2008 was that the banks that emerged unscathed were primarily Asian ones that had learned some harsh lessons during the Asian currency crisis of 1997–98. That historic blowup had been caused by a real estate bubble that bore more than a passing resemblance to the subprime mortgage implosion that laid low many of their American and European peers 20 years later. From Bangkok to Seoul, local banks instinctively steered clear of the problems that ultimately forced their American and European counterparts to sell equity stakes to sovereign wealth funds. The Asian banks thrived by deriving a majority of their income from loans and deposits—as compared with a minority for their Western peers—which made them primarily commercial banks, not investment banks.

But for the past couple of years, the conservative nature of Asian banking has been undergoing a dramatic transformation in favor of risk-taking. Since the global crash, Asia’s big banks have missed few opportunities to rake in fees from investment banking activities, ranging from underwriting initial public offerings and bond issues to advising corporations on mergers and acquisitions. Excluding Japan, which has been in a deflationary malaise for two decades and is only just starting to recover from the devastating earthquake in March, Asia has rebounded strongly from the crash. Thanks largely to a sharp rise in domestic consumption by a combined population of more than 3 billion, Asian countries represent the world’s most powerful source of economic growth, with many of them posting annual rates ranging from 6% to 7%, according to Credit Suisse.

Marching in lockstep, throngs of ambitious Asian corporations are rushing to finance their own breathless expansion plans on stock exchanges from Mumbai to Shanghai. Even household-name European companies are heading east to raise capital. Italian fashion house Prada, for example, tempted by the promise of a higher valuation, chose the Hong Kong Stock Exchange for an IPO that is expected to raise about $2 billion. An added reason for Prada’s choosing to list in Hong Kong is that it already enjoys greater brand recognition among China’s rapidly growing middle class than it does in Europe or the US.

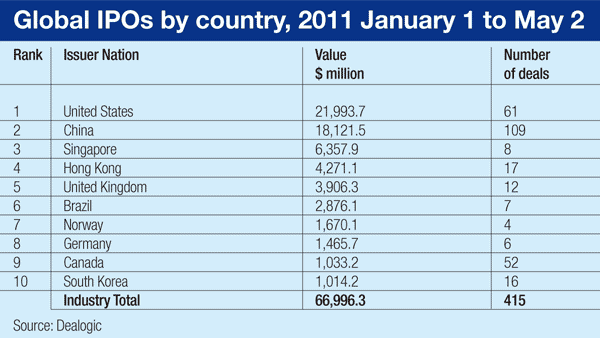

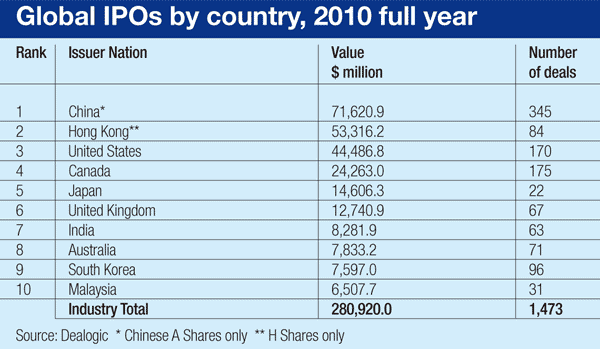

The buying power of Asia’s consumers is a large part of the reason why Asia is now eclipsing other major markets in some aspects of investment banking. The action is clearly concentrated in China, which investment bankers even in New York now grudgingly admit is the world’s most dynamic IPO market. In just over 16 months from January 1, 2010, to May 4 this year, Chinese companies issued $89.7 billion in so-called A-shares for domestic investors and licensed foreign investors in 454 IPOs on the Shanghai and Shenzhen exchanges, making the Communist-ruled country the world’s biggest IPO market, according to Dealogic, a data provider that tracks investment banking. The second largest market is now the US, where a relatively lowly $66.4 billion in stock was issued in IPOs during that period. The third is Hong Kong, which saw $57.6 billion in equity issued in IPOs.

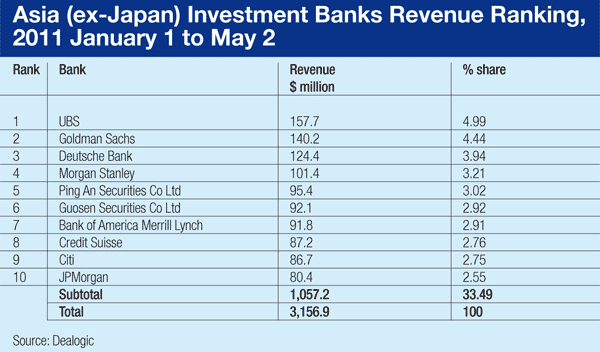

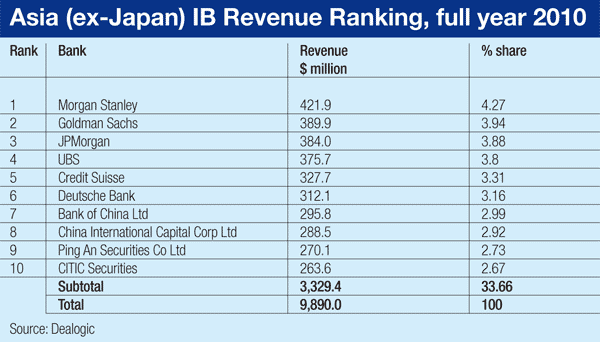

For the time being, the dominant players are still the venerable Western names that have ruled Wall Street, the City of London and Frankfurt for generations. UBS, Goldman Sachs, Deutsche Bank and Morgan Stanley raked in more investment banking fees than any other financial institutions in Asia from January 1 to May 2, taking the top four places in Dealogic’s regional league table.

But as Asia’s capital markets continue to test their upward limits, it’s only a matter of time before Asian investment banks start to overtake their Western counterparts in the region. Thus far the advantage has gone to local banks that were in a position to capitalize on the main trends that are driving economic growth, says Kenneth Lowe, an investment analyst at Matthews International Capital Management a fund management firm in San Francisco that invests only in Asia. Ultimately, they are expected to develop the skills required to compete on an equal footing on international exchanges like NYSE-Euronext and the London Stock Exchange.

“That will take time,” says Helman Sitohang, co-head of investment banking for Asia Pacific at Credit Suisse in Singapore. “I think the Chinese might be able to do it because they have the base and a large-size economy.”

Muscling In

The investment banking subsidiaries of Chinese banks and insurance companies, known as securities houses, are already proving that they can raise enough capital to compete with the global players. Ping An Securities and Guosen Securities were the fifth and sixth biggest earners of investment banking fees in Asia ex-Japan from January 1 to May 2, according to Dealogic. They were followed by Bank of America Merrill Lynch, Credit Suisse, Citigroup and JPMorgan in descending order. “To do a $500 million to $750 million deal, can half of it be swallowed by local investors? Absolutely,” says Sitohang. “That is where the local houses come into play.”

The first step Chinese banks are taking beyond the border of the People’s Republic is in Hong Kong, which Beijing has ruled as a “Special Autonomous Region” for 14 years under its former open-market banking regulations. That arrangement allows foreign banks to compete on a level playing field with the Chinese ones that are bringing companies from the mainland to sell their shares on the HKSE in what they call offshore banking. The 77 IPOs that were underwritten for mainland Chinese companies alone on the HKSE generated $801.6 million fees in just over 16 months from January 1, 2010 to May 2 this year, according to Dealogic.

Four Chinese firms were among the top 10 fee earners from IPOs for mainland Chinese companies in Hong Kong from January 1 to May 2 this year. They were CITIC Securities and Bank of China, which each earned $12.6 million from one IPO each; China Merchants Bank with $2.5 million from two IPOs, and China International Capital with $2.4 million from a single IPO. They were pitching in the same league as the six international banks in this esteemed group, including London-based HSBC, which raked in the most at $16.7 million from three IPOs. JPMorgan Chase earned $11.7 million, Citigroup got $5.4 million, UBS made $6 million, Morgan Stanley pulled in $3.6 million, Goldman Sachs earned $2.6 million, China Merchants Bank received $2.5 million, and China International Capital earned $2.4 million.

Now that they have proved they can keep pace with the giants close to home, the next step for the Chinese investment banks will be to cross national borders into Europe or North America. They are running road shows to talk European companies—such as Prada—into listing IPOs on the HKSE. But they are also making progress in M&A; advisory work. The larger deals are still advised by international banks; Chinese carmaker Geely’s acquisition of Volvo last year was advised by Rothschild, which employs a small army of merger advisers in China. But with the help of local partners, Chinese banks are advising Chinese clients on small acquisitions, notably in Europe, despite rules in Beijing that require two levels of approval because such transactions involve taking capital out of the country.

With China’s increasing focus outside its borders, it’s just a matter of time before Chinese banks start making real inroads into Europe and the US, not just in M&A; advisory but in equity underwriting as well. That will involve building up scale as well as developing the skill to connect one part of the world to another on a global basis, says Sitohang.

Some Chinese securities houses, however, are devising ways to short-circuit the process of building up the skills and scale required to expand overseas. The strategy is to set up cross-border joint ventures with Western players that they hope will carry them across all three channels—domestic, offshore (i.e., Hong Kong) and international—of investment banking. In one such deal that is in the making, CITIC and Crédit Agricole of France announced in May last year that they were in negotiations to integrate their global equity brokerage and investment banking businesses. According to a CITIC spokesperson, the negotiations are progressing.

At the same time, other Chinese banks that once depended on joint ventures with foreign investment banks are showing that they have outgrown their partners. Last December, Morgan Stanley announced that it was selling its 34.3% stake in China International Capital Corporation (CICC), which it had acquired in 1995 to great fanfare as the first Wall Street bank to own a significant interest in a Chinese investment bank. The stake was sold to several buyers—private equity firms TPG Capital and KKR, as well as the Government of Singapore Investment Corporation and Great Eastern Life Assurance. Apart from an expected pre-tax gain of about $700 million, Morgan Stanley’s motive to sell was that its partner “had become so successful that CICC was able to go its own way,” observes Bill Stacey, head of equity at the Hong Kong office of New York–based investment bank Keefe, Bruyette & Woods. Morgan Stanley had inadvertently become a passive investor, he adds. Morgan Stanley issued a statement saying that unwinding the joint venture would allow it to “further expand our domestic market platform and capabilities.”

Ironically, the meteoric growth of China’s equity capital market is to some extent an unintended consequence of concerns shared by bank regulators that regional governments had pressed the largest banks into overextending themselves. In recent years the banks financed an historic infrastructure boom that left the vast mainland crisscrossed with new high-speed rail lines and toll roads and bristling with new airports and skyscrapers. Another concern was that these lenders needed to steel themselves for stricter banking regulations under Basel III. As a result, last year they were compelled to float a total of $70 billion of their own equity, giving China’s stock market a badly needed boost in the wake of the 2008 crash.

One of the most obvious attractions that international investment bankers see in Asia is that its capital markets are still far from mature and thus have great potential, notes Stacey. But different countries in the region are characterized by their own peculiar obstacle courses, which can at times make their capital markets look less profitable and more onerous than those of North America and Europe.

Depending on deal size, the fees that investment banks command in Asia are roughly half the norm on Wall Street. Since 2007, typical IPO fees have ranged from 4% to 6% for a deal valued at $500 million or less in mainland China, and from 3% to 4% in Hong Kong, compared with 6.5% to 7.0% in the US, according to Dealogic. Fees fall progressively for larger IPOs.

|

|

Waking up to a new dawn: China’s investment banks are making their presence felt by bringing Chinese companies to market in Hong Kong and further afield |

Such is the hallmark of a relatively young, fragmented market with a lot of small players energetically pursuing a lot of deals. In Asia the top 10 banks have a combined share of only 34% of the investment banking market, whereas in the US the top 10 players command a daunting 73% share, according to Dealogic.

Another issue is that the region’s markets are developing on a different trajectory from Wall Street. Asia is tilted toward equity capital markets, which last year made up about 57% of investment banking revenue, while debt capital markets account for 20%, loans make up 9%, and M&A; 14%. And M&A; is concentrated in the oil and gas industry, which accounts for 15% of announced volume, according to Dealogic. In comparison, 32% of investment banking revenue in the US is in debt capital markets, 22% in loans, 24% in M&A; and 22% in equity capital markets.

And then there are the tight restrictions that most regulators in the region, excluding those of Hong Kong and Singapore, impose on foreign banks. The most onerous of these rules are enforced in China, where foreign banks are required to form joint ventures with local ones and are only allowed to own minority stakes.

Yet foreign bankers do not complain openly about these issues, and they are not about to bolt for the exits. “International banks are willing to forgo fees to maximize their league table positions,” notes Stacey. And China’s banks are not just watching and learning from their international peers. “There is a lot of competition to bring in rainmakers,” he adds. Before long, such coveted bankers could be headed not just for the corner offices of Goldman or JPMorgan in Hong Kong but also into the open arms of CITIC or CICC in Shanghai.

Matthews International Capital Management