CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

The dollar has been drifting lower this year on expectations that the Federal Reserve will lag behind other developed-market central banks in raising interest rates to fight inflation, analysts say.

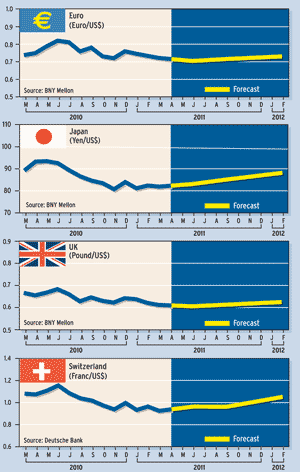

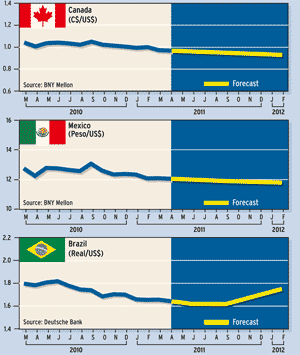

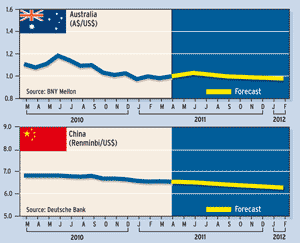

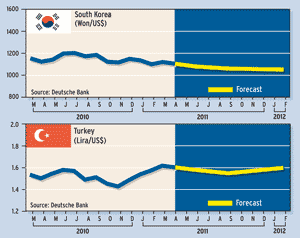

Currency Forecasts

The euro neared a four-month high against the greenback in March as the European Central Bank put the markets on notice that it could raise interest rates as early as this month.

Marc Chandler, New Yorkbased global head of currency at Brown Brothers Harriman, says the foreign exchange market is being driven by one overriding consideration: The ECB is going to raise rates, while the Fed is standing pat. The euro rose last month even as Moodys Investor Service downgraded Greeces debt by three notches and cast doubt on the governments ability to implement its austerity program. The debt crisis on the periphery of Europe has been ignored by the market, Chandler points out.

Meanwhile, traditional relationships between the value of the euro and the price of oil, gold and commodities appear to be breaking down. One reason for this is the divergence between the ECB and the Fed in monetary policy responses to the rise in food and energy prices, Chandler explains.

While the eurozones headline inflation is 2.3% at an annual rate, the US headline consumer price index is near 1.6%. The Fed is more likely to look past a suspected temporary rise in headline inflation, as long as the core [inflation rate] remains subdued and inflation expectations [stay] anchored, Chandler says.

Michael Woolfolk, managing director at BNY Mellon Capital Markets, says Fed chairman Ben Bernanke can legitimately point to continued weakness in the US labor market when explaining the need for near-zero-percent interest rates and continued quantitative easing. However, ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet cannot. Not only is European inflation rising at a faster pace than in the US, but the ECB also does not have the luxury of using high unemployment as an excuse to maintain monetary accommodation, Woolfolk says. Unlike the Feds dual mandate, the ECBs mandate is quite clear: maintain price stability in the medium term.

With the Fed on hold and the ECB mounting a campaign against inflation, the euro is well positioned to rally further, Woolfolk says. While the US unemployment rate unexpectedly fell to 8.9% in February, its third decline in three months, this is not, he adds, a particularly positive development. Rather than reflecting job growth, the drop in the unemployment rate appears to be driven to a great degree by people dropping out of the labor force, Woolfolk says. A remarkable 1.4 million people have fallen out of the labor force over the past six months.

Meanwhile, Trichet and the ECBs governing council are obviously deeply concerned about the recent rise in food and energy prices and the potential for second-round effects worsening the inflation rate, Woolfolk says. The ECB will do whatever is necessary to maintain price stability, and further rate hikes [after April] cannot and should not be summarily dismissed.

David Gilmore, partner and economist at Foreign Exchange Analytics, based in Essex, Connecticut, says he was astonished by Trichets announcement of a preemptive strike against inflation. Even Trichet conceded that there were no signs of pass-through inflation from higher commodity prices, Gilmore says. What does this mean for the euro and the dollar? Well, one of the two ugly currencies is looking a little less ugly, he says. The euro should eventually move into a new trading range of $1.40 to $1.50, Gilmore believes. The markets are focusing more on the US deficit-funding hole ahead when the Fed starts buying a lot less US debt, he says. But what about the unexpected consequences of the ECBs exiting easy monetary policy while maintaining its unconventional bank-support policy? This will mean more pressure on bank profits as the cost of funds rises. But more concerning is the impact tighter monetary policy and rising rates pose for the [peripheral] countries of Europe, Gilmore says. A rising euro and rising borrowing costs, on top of already unsustainably high borrowing costs, will be added to the pain of being pressured to improve competitiveness through austerity, he notes.

The ECB delivered a complete surprise to the market by signaling a likely rate hike in April on the one hand, while on the other hand keeping the fixed-rate-with-full-allotment policy of supplying reserves in all open-market operations in the second quarter, according to a report by Bank of America Merrill Lynch Global Research. In his press conference following last months meeting, Trichet repeatedly referred to the separation principle as he explained the ECB governing councils decision to separate the banks interest rate policy from its liquidity operations. By signaling rate hikes in the near future, while allowing the commercial banks to continue to decide how much liquidity they obtain from the central bank, the ECB has further complicated the task of extracting information about the markets ECB policy expectations, the BofA Merrill Lynch analysts say.

Paul Robinson, London-based head of European foreign exchange strategy at Barclays Capital, says the euro could experience some short-term weakness due to the problems of the peripheral countries, but it should recover once the results of the European bank stress tests, which are currently under way, are released. The tests are expected to be much more rigorous than last years.

The stress test results are particularly crucial for the euros prospects because European banking fragility is one of the most obvious channels through which problems in the peripheral economies may lead to serious economic consequences in the core economies, Robinson says.

The Middle EastNorth Africa crisis seems likely to lead to higher oil prices for some time, he adds. This is a negative factor for the dollar for several reasons, Robinson says, in addition to the differing monetary policy responses between the central banks. The US terms of trade will be worsened, and the shift of wealth from oil consumers in Asia to oil producers will have a negative effect on dollar-denominated assets, he says. The oil exporters have a lower preference for holding dollars than the oil importers in emerging Asia, particularly China.