SECTOR FOCUS — ISLAMIC FINANCIAL SERVICES

By Anita Hawser

Calls for standardized regulation of Islamic financial services are growing louder in the wake of the global financial crisis.

Islamic banks emerged from the recent financial crisis with a relatively burnished image. Unlike their conventional counterparts, which built up too much leverage, Islamic institutions’ ethical approach to investment shielded them from catastrophic asset write-downs. But Islamic financing operates within and alongside the conventional financial system, which is undergoing a major regulatory overhaul. As a result, Islamic finance is also seeing an increase in regulatory interest.

Although the first Islamic bank was established in the 1970s, it is only in the past decade or so that Islamic banking has really come into it own, growing at a rate of up to 15% per annum. It is also increasing in complexity with the development of more sophisticated products that bear a striking resemblance to those in the conventional world. Islamic finance has also spread to non-Muslim countries—particularly France, UK, Hong Kong and Singapore—that are looking to attract Middle Eastern money by establishing themselves as Islamic financial centers. So although the financial crisis did not start in Islamic finance, those charged with overseeing its steady progression on the global stage recognize there are many lessons to be learned from the recent crisis.

That appears to be the rationale of the Task Force on Islamic Finance and Global Financial Stability, which was formed in October 2008. “As authorities worldwide are working hard to reform financial systems and policies, this will be a suitable time to give the Islamic financial industry the opportunity to participate in the process,” the Task Force stated in its April 2010 report, Islamic Finance: Global Financial Stability, published in conjunction with the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and the Islamic Research and Training Institute. “The global financial crisis has demonstrated that we face common challenges,” the report added.

At a Malaysia International Islamic Financial Center (MIFC) event in Kuala Lumpur last November, Bank Negara Malaysia’s governor, Zeti Akhtar Aziz, who headed up the task force, stated that Islamic finance’s supervisory and regulatory infrastructure needed to remain relevant to the rapidly changing world. She said there needed to be regulatory cooperation to address new challenges that emerge and also spoke of the need to strengthen the liquidity management capabilities of Islamic financial institutions. Not only were they not as well capitalized as conventional banks, but there was also a lack of financial instruments for helping them raise liquidity. “A strong liquidity management infrastructure needs to be urgently addressed in Islamic finance to enhance the ability of Islamic institutions to raise liquidity,” stated Aziz.

One of the prudential bodies that oversee Islamic finance, the Islamic Financial Services Board (IFSB), which has 50 regulatory authorities as members, established a liquidity task force in conjunction with the IDB to develop a liquidity management framework. That culminated in the announcement on the sidelines of the annual World Bank and IMF meetings in Washington last month of the formation of the International Islamic Liquidity Management Corporation, which will issue “liquid, short-term shariah-compliant instruments” to help Islamic financial institutions better manage their liquidity. The IILM will be based in Malaysia and is expected to commence operations this year.

Aziz’s Task Force also highlighted the need for a more globally coordinated and integrated approach to Islamic financial services in order to ensure that the Islamic financial system as a whole “is able to withstand shocks and adverse market developments.” At the MIFC event last November, Rifaat Ahmed Abdel Karim, secretary general of the IFSB, stated that there are risks specific to Islamic financial institutions that need to be taken into consideration, meaning that regulations applying to conventional banks need to be adapted to address some of the specificities of Islamic finance. But in its efforts to enhance the “soundness” of Islamic finance, he says, the IFSB is mindful of not exposing the industry to tougher standards, which could put it at a disadvantage.

Risk Management Concerns

The financial crisis did highlight some risk management issues within Islamic funds and financial institutions, particularly those exposed to real estate assets. Some maintain that if Basel II had been more widely implemented by Islamic institutions, overexposure to real estate assets might have been avoided. Yet, Qatar-based Amjad Hussain, Islamic finance partner at international law firm Eversheds, says concentration risk in the real estate sector is not about Islamic financing per se as conventional financial institutions were also exposed to that sector. With respect to international regulations like Basel II, he says it takes too much of a “broad-brush” approach. For example, he says, Basel II attaches a higher risk weighting to those financial institutions that lend to companies they also have an equity stake in. However, under a musharaka arrangement in Islamic finance, holding equity is often a key part of how projects are funded. “If you put a higher risk rating on them, that makes it cumbersome for Islamic institutions to offer some of these products as they are deemed to be engaging in risky activities,” he explains. Applying regulations such as Basel II to Islamic institutions without taking into account how Islamic institutions operate is dangerous, he adds, as Islamic finance, if practiced in its true form, has a number of built-in safeguards to protect both parties in a transaction. Given these fundamental differences, he maintains that the argument for regulating Islamic finance separately from the conventional financial system (or at least in a tailored manner) is compelling.

However, Rod Ringrow, a senior vice president at State Street, says it is too easy to say that there is no need to further regulate Islamic finance because it was not directly impacted by the crisis. Given that a number of Islamic products mimic conventional finance, he says, “we are likely to see more regulation and more commonality in regulation between conventional and Islamic finance.” In a recent Islamic finance leaders’ report published by consultant Deloitte, which surveyed executives, practitioners and policymakers from the Middle East, Islamic accounting standards and risk management were highlighted as the top two areas requiring new regulation. Sixty-six percent of respondents said the Islamic finance industry was under-regulated, and there were wide-ranging views on the level of Islamic finance supervision in the GCC region, with 24% saying it was low and 46% saying it was neither low nor high.

The perception that Islamic finance is under-regulated perhaps stems from the fact that in those countries where Islamic institutions are regulated in parallel with conventional firms, shariah jurisprudence or oversight largely rests with individual scholars sitting on the boards of Islamic finance institutions and conventional financial institutions with Islamic “windows.” Shariah jurisprudence also differs from region to region, with a financial instrument that is considered acceptable in one region being forbidden in another. So for some, regulating Islamic finance goes hand in hand with enforcing more standardization. “There is a view that there should be a greater commonality of definitions as to what makes a product shariah [compliant] or not,” says Ringrow, “as a way of getting the market to deepen and develop further.”

For Michael Rainey, a partner in the Middle East and Islamic finance practice at lawyer King & Spalding, no debate about regulating Islamic finance is complete without a discussion on standards. “What is deemed to be shariah-compliant is for the most part decided by the shariah board of a particular institution,” he says, “and if you are talking about regulating the industry, that to me is the crux of it as that is what distinguishes it from the conventional financial industry.”

Organizations such as Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions and the International Islamic Financial Market already play a role in setting standards. The IIFM developed standardized master agreements for treasury placement and hedging. AAOIFI produced accounting, corporate governance, auditing and shariah standards. It is currently reviewing these standards as well as developing new standards in areas such as real estate, takaful (insurance), risk management and shariah supervisory boards. Yet Hussain says having one uniform standard that is applicable across all jurisdictions is not what Islamic financing is about and is not practical. “One size does not fit all as you will always have the issue of local law,” he says.

Scholarly Debate

Another topic that is causing much debate in Islamic finance circles concerns scholars who sit on shariah advisory boards within financial institutions. Questions are being raised about potential conflicts of interest among these scholars, as well as the compensation they receive or shares they may have in these institutions. When it comes down to who should police or regulate these scholars, Hussain says some would reply the Almighty Allah regulates them. “What better regulation than their own conscience?” He says it is not about regulating scholars but more about whether the industry has a sufficient talent pool of scholars that understand both shariah law and banking.

|

|

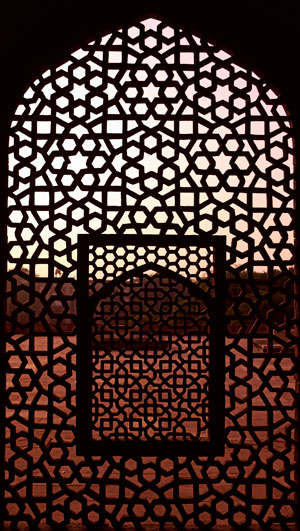

Kuala Lumpur: Aiming to be a global standard-setter in islamic finance |

In Malaysia, for example, the central bank established a shariah advisory council that determines what is shariah-compliant. But at a global level, the approach is still fragmented. Recent reports talk of a Gulf-wide shariah council that has the regulatory muscle to set mandatory standards—a suggestion that appears to be emanating from the Bahrain-based AAOIFI. Hussain says a Gulf-wide shariah council is a good idea, but given the problems the GCC countries have had in introducing a common currency, he questions how such an organization would work in practice. And although Malaysia is perceived to be the leader when it comes to shariah governance, “The Malaysian model may not be acceptable around the world,” says Rainey. “I don’t think you will get a shariah advisory council in London or Paris.”

Although there is a growing consensus as to what is shariah-compliant and what isn’t, particularly for more widely traded instruments like sukuk, Rainey says some Islamic financial centers may not want to adopt AAOIFI’s standards. But if AAOIFI wants to be a global regulator and encourage greater levels of standardization, he says it may have to emulate the UK’s FSA by “naming and shaming” those firms that fail to adhere to the standards it sets. However, Hussain maintains that AAOIFI’s standards do not need to be binding, “as central banks in each country should be developing their own locally adjusted view, not just adopting AAOIFI’s view” of what their country needs.

Shariah principles are always going to need to be backed up by the existing legal regime of a particular country. And although there are legitimate differences of opinion among the recognized schools of Islamic jurisprudence in certain areas, Hussain says the real issue is not about the uncertainty this produces but about the vacuum that exists in prudential regulation and supervision because of the laissez-faire approach adopted by many regulators and central banks. “Some regulators need to get to know the organizations they regulate better,” he says.