CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS – FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

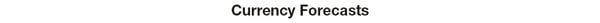

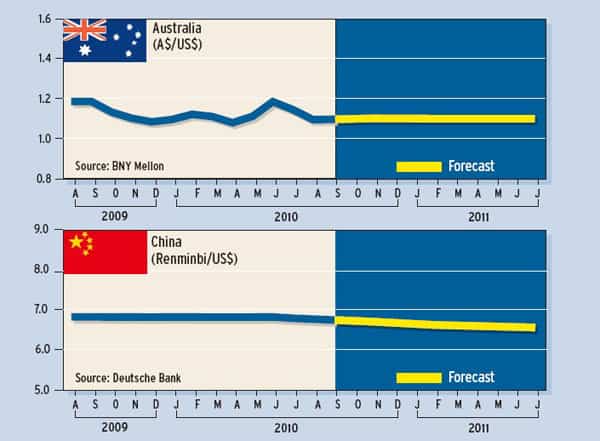

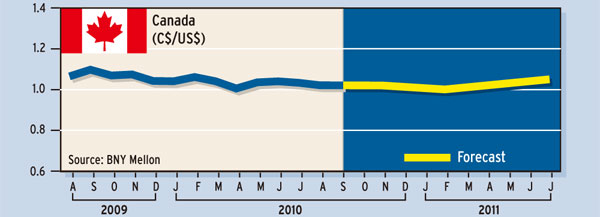

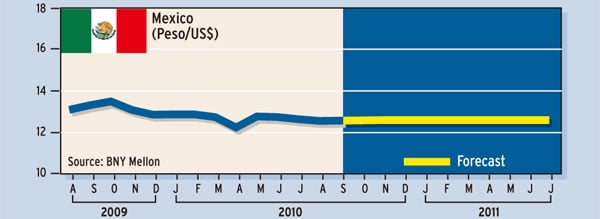

The Federal Reserve is likely to keep US interest rates at record lows well into next year, enabling global investors to borrow dollars for a song and invest in higher-yielding assets in countries such as Australia and South Africa. The dollar is increasingly being used to fund the carry trade, as foreign-exchange market volatility recedes and risk appetite grows stronger, analysts say. The greenback’s trend has been clearly downward since stock and bond markets turned higher over the summer months.

“Amidst the summer doldrums of July and August, not only has liquidity dried up but so has volatility,” says Michael Woolfolk, senior currency strategist at BNY Mellon. As volatility has continued to ease, the carry trade has returned.

Funding investments in higher-yielding currencies with dollar-denominated loans lost money for investors earlier this year, in part because the dollar was rising. With the greenback falling once again and a Fed rate hike pushed further into the future, the strategy has gained new appeal.

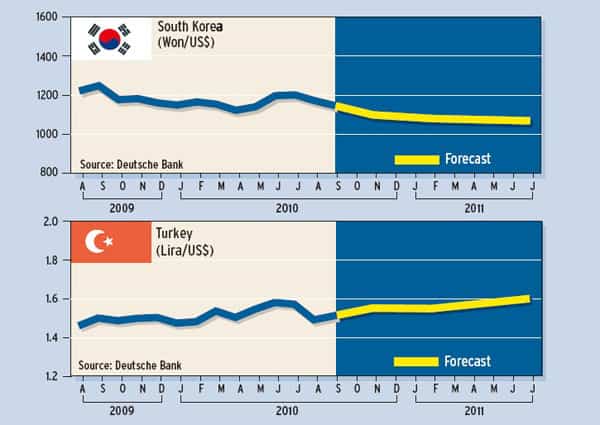

What happened to change the direction of the euro? A weaker US economy and a stronger eurozone economy played a big part, according to David Gilmore, partner and economist at Essex, Connecticut–based Foreign Exchange Analytics. US housing and employment data showed signs of weakness, and it also became clear that banks were not doing much lending, Gilmore says.

Meanwhile, the bank stress tests in Europe showed that only seven of 91 banks had failed. “While the stress test looked more like a whitewash than a fact-finding mission to me, to others it was another all-clear [signal] for buying the euro and risk assets and selling the dollar,” Gilmore says. The market may have been too one-sided in early June, when the euro slipped below $1.19, but it is now in danger of losing sight of significant risks to the euro, he adds. “

The very real strains in the banking system in the spring were not unfounded, and no whitewashing of balance sheets in the latest stress test can fix what is broken,” Gilmore says. “Ongoing reluctance of banks to lend to each other and a still-heavy dependence on the European Central Bank for funding and parking toxic assets are not constructive for growth.” Deleveraging, loan-loss provisioning and capital-raising efforts are all still ahead for Europe’s banks, not behind them, as is the case in the US, Gilmore says. And while the US economy ran into problems in May and June, it did not die, he adds.

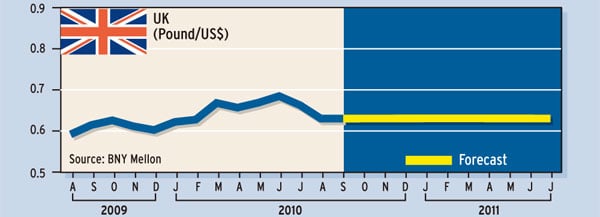

Dollar weakness has stemmed from disappointing US economic data, a reduction in eurozone risks and the positions held by market participants, according to analysts at Barclays Capital, the investment bank arm of UK-based Barclays Bank. The analysts predict there are modestly better times ahead for the dollar, as it does not expect those three trends to continue. “We continue to think there are significant political risks around the euro and the British pound.” The bank stress tests revealed the structural challenges still faced by the eurozone, they say. And in the UK, although the coalition government has agreed to significant spending cuts, implementing these cuts is another matter, they add.

Economic data are likely to remain the strongest driving force for the dollar, according to Barclays Capital. “We think it is unlikely that Europe’s economy can continue to strengthen while the US economy struggles,” its foreign-exchange research department says. “And a lot of bad news has already been priced into the dollar on the economic front.”

Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman, says there is a risk that investors are overreacting to the short-term volatility in macroeconomic reports. “Quantitative easing, or what the Fed has called credit easing, is an emergency mechanism,” he says. “While the US economy is still strained and restrained by structural impediments, it is hardly an emergency that can be addressed by tweaking the Fed’s balance sheet.”

The dollar’s slide has been of sufficient duration and magnitude to encourage momentum traders and model-driven funds to take short positions in the greenback, Chandler says. “The European experiment of monetary union without political union is not collapsing, as many had thought it would a couple of months ago,” he says.

The Japanese yen’s rise to the highest level since last November and close to a 15-year high is more a case of the dollar’s weakness than of the yen’s strength, according to Chandler. “The appreciation of the yen is a symptom of the private-sector challenge in recycling the combination of Japan’s current account surplus and foreign purchases of Japanese assets,” he says.

The yen’s rise may aggravate the deflationary forces in Japan, Chandler ventures. “This suggests that, rather than intervene in the foreign exchange market, the ministry of finance may intensify pressure on the Bank of Japan to take additional steps, such as increasing its purchases of Japanese government bonds or expanding existing lending facilities,” he says.

Meanwhile, new data from monetary authorities around the world show that the average daily volume of trading in the foreign exchange market has increased to $4.1 trillion, according to an analysis by HSBC ahead of the official release of aggregated data by the Bank for International Settlements. In April 2010, foreign-exchange trading volume was 28% higher than in April 2007, the date of the last central bank survey. That was far slower, however, than the 65% increase seen in the period from April 2004 until April 2007.

The volatility surrounding Europe’s sovereign debt crisis boosted foreign-exchange trading activity by 12% in the US and 15% in the UK from October 2009 to April 2010. London remained the main global center for currency trading, accounting for approximately 43% of the total, and the dollar-euro currency pair was the most actively traded in the UK, the Bank of England announced in its report.

Global deleveraging and the failure of Lehman Brothers caused foreign-exchange trading activity to decrease significantly between April 2008 and April 2009. Traders reduced their risk exposure and unwound carry trades aggressively during this period. The central bank surveys measure spot currency transactions, outright forwards and foreign exchange swaps.