COVER STORY: FINANCIAL REGULATION

By Justin Keay

Businesses can expect to see their top-line costs rise under new banking regulations in the US and Europe. Will it be money well spent?

If in pre-credit-crunch days policymakers uttered the phrase “financial regulation,” it was as the antithesis of what then defined global finance. In the US, which in 1999 repealed the Glass-Steagal Act that had separated investment banking from commercial banking since 1933, and the UK, which since the 1997 creation of the Financial Services Authority (FSA) had enthusiastically promoted increasingly “light-touch regulation,” the concept seemed archaic. Securitization was the new religion, and further deregulation looked inevitable, with governments, companies and consumers all in thrall to the brave new world of derivatives, synthetic collateralized debt obligations and hedge funds.

If in pre-credit-crunch days policymakers uttered the phrase “financial regulation,” it was as the antithesis of what then defined global finance. In the US, which in 1999 repealed the Glass-Steagal Act that had separated investment banking from commercial banking since 1933, and the UK, which since the 1997 creation of the Financial Services Authority (FSA) had enthusiastically promoted increasingly “light-touch regulation,” the concept seemed archaic. Securitization was the new religion, and further deregulation looked inevitable, with governments, companies and consumers all in thrall to the brave new world of derivatives, synthetic collateralized debt obligations and hedge funds.

That era now looks as distant as the Edwardian summer that preceded the outbreak of hostilities in August 1914. As financial institutions gloomily mark the third anniversary of the beginning of the global crisis—when the subprime problems first became clear—every second person holds views on the once-abstruse subject of financial regulation, differing only as to how far it should be tightened and how severely banks should be punished. Banks have been fighting a tough rearguard action, saying excessive new rules could further devastate lending and, consequently, global economic prospects.

Meanwhile policymakers have been caught in the middle, facing criticism they are merely reacting to a crisis that has already happened rather than preparing for the next one.

In the European Union in July, a time officials used to spend packing for their summer vacation, regulators at the Committee of European Banking Supervisors unveiled the results of stress tests on 91 banks. Seven failed (five from Spain, one each from Germany and Greece), prompting criticism that the tests were insufficiently strong, transparent or realistic enough, despite the fact that 27 banks in Spain (including regional cajas), six in Greece (the country at the center of the sovereign debt whirlwind for the past year) and 14 in Germany, including Landesbanken, were all tested for the first time.

The results came just three weeks after the European Union, in an effort to curb excessive risk-taking at banks, hedge funds and asset management firms, imposed new curbs on bonuses. Immediate cash payouts are now limited to 30% of the total, with the remainder deferred and linked to long-term performance. The UK’s FSA—which since its much-publicized failure to anticipate the crisis at Northern Rock in 2007 has been bending over backwards to be vigilant in such areas as financial crime—earlier published even tougher new rules that may be beefed up by the new coalition government.

The New Credit Squeeze

For corporates and individuals, the big question is to what extent all this activity will affect their relationship with the banks. In the US, according to the Fed, commercial and industrial lending dropped some 22% to $1.24 trillion over the first half of 2010—and that’s before the new regulatory package comes into effect. Small businesses in Europe have been complaining that some three years after the start of the credit crunch, access to bank loans remains as tough as ever, despite the fact that many lenders are now under state control and despite governments’ urging banks to facilitate economic recovery by being less risk-averse.

Meanwhile, according to the ratings agency Standard & Poor’s, securitization has slowed dramatically from €500 billion ($650 billion) in the first half of 2009 to just €39 billion in the same period this year.

The consensus is that greater regulation, whether manifested through higher capital or liquidity requirements, enhanced consumer protection legislation or simply higher compliance requirements, will further depress lending and lead to higher client costs as loans and services become pricier. “Spreads on corporate loans and mortgages will inevitably be much higher…indeed, there are signs this is already happening,” says Michael Foot, chairman of the UK arm of the Washington, DC–based Promontory Financial Group and before that a senior regulator at the Bank of England and then the FSA.

Mark Plotkin, a regulation specialist at the Washington, DC law firm Covington & Burling, agrees, saying his clients have increasingly been expressing their concerns about rising regulatory costs. “Congress doesn’t want to admit it, but all this activity will add to the bottom line for banks and their clients. In addition, regulators are under enormous political pressure to prevent future crises. As a result, banks are increasingly questioning loans, becoming more risk-averse and charging more,” he says.

Banks have also been holding back from making loans because of the uncertainty surrounding Basel III, the bank regulation accord to be enacted in the coming months. Although not due to become effective until 2012, the provisions regarding how much capital institutions must hold remain unclear; this has led many potential investors to hold on to cash rather than lend it to corporates.

A Brave New World

What nobody doubts is that financial regulation in the Western world is undergoing the most dramatic change since the Great Depression. In the US, the passage in July of the complex, 2,300-page Dodd-Frank Act inaugurated a new era in finance in which the Fed will essentially become a systemic risk regulator. President Barack Obama says the US taxpayer will never again have to finance bank bailouts. There was, however, widespread disappointment among the bill’s proponents that a proposed $19 billion levy on financial institutions was abandoned to secure the support of key Republicans.

A national banking regulator will have a wide range of new powers over both savings and commercial banks. It will have special powers over larger institutions, which will now be required to have so-called living wills to safeguard investors in the event of the banks’ failing. The regulator will also be empowered to take these institutions over to address the contentious “too big to fail” concern. A new Council of Regulators will pull together input from the various regulatory institutions, while consumers will be covered by a new Consumer Protection Agency, drawing the powers from seven agencies into one. In a radical departure from current practice, hedge funds, private equity firms and credit ratings agencies will now have to register with a vastly expanded SEC, with CRAs being closely monitored for any conflicts of interest. In addition, derivatives trading will be regulated, curbs will be imposed on retail banks engaging in proprietary trading, and new guidelines will be released for bankers’ pay.

There has been criticism over the Act’s failure to fully tackle the fragmented system of US regulation or clarify the extent of federal and state responsibilities—Plotkin says states will actually regain the right to regulate on consumer protection, for example—and the fact that much of the legislation will take years to implement. There is also criticism that Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac remain unreformed, despite the fact they have already absorbed almost $150 billion of taxpayers’ money. However most analysts agree the reforms constitute a move in the right direction, not least because they address systemic risk, with the Fed given the central role.

“It isn’t perfect, but we can’t let perfect get in the way of good,” the US ambassador to London, Louis Susman, told a gathering of bankers in London in mid-July. “This package gives the message that we will not allow certain past practices to continue.”

Europe Tightens Up

Changes proposed by the European Commission for EU countries are no less far-reaching. Although the precise details will not be known until later this month, three existing regulatory bodies for the banking, securities and insurance industries will be enhanced to become European Supervisory Authorities. Based in London, Frankfurt and Paris, the ESAs will work with national regulators but are to be given powers to intervene in cross-border and other issues. Meanwhile a new European systemic risk board will oversee financial issues and work with the authorities to prevent the outbreak of future crises.

Alongside all these changes, international regulators and supervisors are discussing Basel III, which they hope to get agreement on by early 2011. Proposals will center on financial institutions’ implementing new capital and liquidity rules and tightening leverage regulations.

Many bankers, not surprisingly, have voiced fears that the weight of new regulation, besides pushing up operating costs and, by extension, costs to customers, may prove counterproductive. They have been fighting many of the proposals put forward for Basel III, including that they be required to hold sufficient liquid assets to cover liabilities for one year and that, regardless of their size, they will face limits on the ratio of total assets to total capital. Banks say such steps would devastate their activities and have a major economic impact: The Institute for International Finance, for example, says excessive tightening of international banking rules could trim GDP growth in the developed world by some 3.1% over the next five years.

And that’s not all. At the British Bankers’ Association (BBA) conference in London in mid-July, Gordon Nixon, president and CEO of Royal Bank of Canada, said that pushing all banks in the same direction and obliging them to abide by the same set of rules could actually increase the risk of another crisis. Similarly, restrictions on proprietary trading are deemed a step too far, especially as it was not a factor in the demise of such banks as Bear Stearns or Lehman Brothers. “The sector needs to remain diverse…What it needs is not just more regulation but smarter regulation,” he said, also voicing doubts about the complexities surrounding the modeling in Basel III. “Banks that failed real-life stress tests may find themselves failing these theoretical ones,” he added.

|

|

Nixon: “The sector needs to remain diverse … It needs smarter regulation” |

Other observers are more concerned about the lack of international cooperation, pointing out that a level playing field is vital. “Without doubt, fragmented policymaking will lead to regulatory arbitrage, dissipated capital flows and a negative economic impact. We need a consistent, joined-up approach to regulation,” says Deven Sharma, president of Standard & Poor’s.

Pierre Delsaux of the European Commission says he hopes the G20 will follow the European Union’s regulatory lead but admits the risk remains that Brussels could otherwise be creating a competitive disadvantage for the 27 EU countries.

Some say the process has already started with the US decision not to implement a bank levy, which puts it at odds with other financial jurisdictions. “The US moves are in the right direction, but Dodd-Frank is a politically motivated law and parts are not that well thought out,” argues Mark Plotkin. As well as regulatory arbitrage, he is concerned about high compliance costs leading to a tightening in credit and further economic slowdown once the new regulations kick in.

Caution May Heighten Crisis Risk

Those who argue that the financial system is still vulnerable are concerned that policymakers may delay implementation of new capital, liquidity and leverage rules because of fears about economic growth. “If these [rules] are not increased, we run the risk of another financial crisis happening sooner rather than later,” says Promontory Financial’s Foot.

There have been many other criticisms, including about the EU’s stress tests, with the IMF, among others, suggesting they lacked transparency and failed to take sufficient account of banks’ sovereign risk exposure.

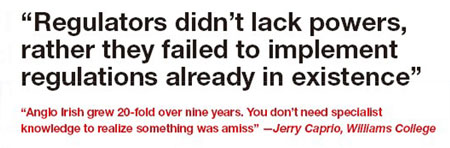

For some observers, moves to enhance regulators’ powers amount to trying to shut the barn door long after the horse has bolted—in essence to create a better yesterday. “If you look at the countries where the crisis hit hardest—the US, UK, and Ireland, for example—regulators didn’t lack powers, rather they failed to implement regulations already in existence,” says Jerry Caprio, a regulation specialist at Williams College in Williamstown, MA.

Co-author of a forthcoming book about regulators, Caprio, who previously worked at both the IMF and World Bank, is very skeptical about their performance. He suggests they retreated in the face of market innovations they could not understand. In the most extreme cases, such as Northern Rock in the UK and Anglo Irish Bank in Ireland, which grew at a phenomenal rate on the back of the Irish property bubble, he claims regulators simply didn’t do their job. “Anglo Irish grew 20-fold over nine years. You don’t need specialist knowledge to realize something was seriously amiss there,” he says, arguing that governments haven’t done enough to hold regulators to account. He proposes a new watchdog for regulators—a sort of regulator’s regulator—to meet regularly to determine the level of systemic risk and what regulators are doing. Such a body should comprise professionals from Wall Street and elsewhere, which would make it expensive but also hopefully effective.

Caprio is heartened that the EU’s plan to set up a European Systemic Risk Board to monitor risks to the system goes some way toward this but admits that he isn’t sanguine about the future. “Despite all the talk, we are not getting enough real change in the way regulation is done. Taxpayers should quake in their boots if another financial crisis blows up,” says Caprio.

|

It’s a muggy, almost oppressively hot day in the City of London, and the mood inside the annual meeting of the British Bankers’ Association is almost as heavy, as bankers face a future filled with uncertainty. “There’s a sense here that these masters of the universe can no longer even control their own destiny; that their future now lies in the hands of people—politicians and regulators—they have long looked down on,” says a leading British finance lawyer, opting not to be named.

Little wonder. The country that for the past 30 years led the world in financial deregulation is now setting the pace in re-regulation. Bankers were told they may face new taxes on profits and pay on top of a £2.5 billion($4 billion) levy already imposed in the national budget earlier this year. During the day, Treasury Select Committee chairman Andrew Tyrie then told them he was launching an inquiry into retail bank competition in the wake of the mergers and takeovers that took place during the financial crisis, and into increased bank concentration. He warned that the government would consider breaking up the banks, a pet project of business secretary Vince Cable. “I don’t see the logic of arrangements that would complicate restructuring the economy and which other countries have rejected,” says BBA chief executive Angela Knight.

In the meantime bankers have been preoccupied with the radical reforms unveiled in June by UK finance minister George Osborne, that will see the Bank of England assume a key position in Britain’s regulatory architecture and spell the abolition of the once-heralded single regulator, the Financial Services Authority (FSA). These embrace the so-called twin peaks model of regulation. Under this model, regulation is essentially split, with one organization—in the UK’s case, the Prudential Regulatory Authority within the central bank—responsible for regulation of non-consumer-facing financial institutions and another—the new Consumer Protection and Markets Authority—responsible for retail financial services providers. “If you look at financial crises in the US, for instance, it was the nonbank organizations—AIG, Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac—that caused the crises because they were not being regulated. Under twin peaks they will be,” says Michael Taylor, one of twin peaks’ earliest proponents.

|