FACING UP TO THE CHALLENGE

The fast-growing and dynamic economies of the emerging and frontier markets represent mouth-watering opportunities and daunting challenges for the world’s established multinationals. Only the best prepared will survive.

By Amy E. Buttell

Humbled by the recent recession, dogged by uncertainty over global economic prospects and haunted by growing political risks, the typical Western multinational is facing a daunting operating environment. But according to a growing chorus of analysts, their world is only going to become more challenging. The newest threat—and perhaps the most unnerving—is the growing throng of hungry, cash-rich and dynamic companies bursting out of the emerging markets and onto the world stage.

As emerging markets develop further, companies based there will continue to move up the food chain, pressuring companies in developed countries on the high end with more sophisticated goods and services. At the same time, frontier economies will expand their presence and will squeeze companies in developed and emerging market countries on the low end with low-cost production. For those who are enjoying the status quo, that is the bad news. The good news is that the rise of a gigantic emerging middle class in emerging and frontier countries will present enormous opportunities for companies in developed countries to sell a wide variety of goods and services.

The pending shift of power in trade is far from just an expansion of what is going on right now, says Uri Dadush, senior associate and director of the International Economics Program at the Carnegie Institute for International Peace, a think tank based in Washington, DC. “Developing countries will be the central players in trade,” he says. “They will account for two-thirds of world trade, whereas they account for about a third today.”

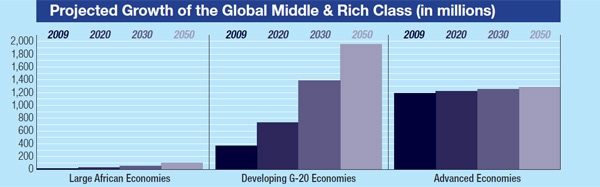

According to Dadush, there are three key developments taking place. “Developing countries will be growing essentially by invading the traditional territory of industrial countries by manufacturing more and more sophisticated products,” he says. Secondly, “developing countries will have more of a middle and rich class that will be able to afford to buy sophisticated consumer products. The third trend is that developing countries will become much more integrated financially with each other and the main financial centers,” he adds.

These trends have been accelerated by the financial crisis, which has left many developed countries struggling while emerging and frontier countries have recovered quickly and are growing more rapidly. To compete in this new trade world, which Dadush believes will evolve over the next 40 years, US-based multinationals will have to become more nimble than ever in developing products and services for this rising emerging market middle class, while fending off competition from companies in those same countries that are trying to grab a bigger slice of the world trade pie.

New Consumers Drive Market Change

The biggest factor in the emergence of the developing world as a powerful and rising trade power is economic growth. As the developed world struggles to find its way out of the recent recession, the developing world is growing rapidly. “Emerging market countries are growing, and many are growing rapidly,” says George Haley, a professor of marketing and international business at the University of New Haven. “There’s a group of emerging market countries where newly industrialized markets are developing, not just China and India, but others like Brazil, Mexico and Ghana.”

Within those countries is a rising middle class poised to earn larger incomes, increasing their appetite for more sophisticated goods and services. The Carnegie Institute says the rapid economic growth of developing countries will lead to the emergence of a “new global middle and rich class.” This class will be able to demand more overall and will increase the demand for advanced goods and services, rapidly expanding the markets for internationally traded goods, such as automobiles and consumer durables. “The people in this class are also likely to demand more and better education, health and international tourism services,” the institute says.

While multinationals in the developed world are in a strong position to capture a sizable share of these markets, it is not a sure thing, because companies in emerging and frontier markets are growing more sophisticated in their ability to compete in these same sectors. It is this sophistication that might wrong-foot complacent Western businesses. “We tend to believe that emerging countries, emerging economies, are less sophisticated and less technologically advanced than we are,” says Jon Younger, administrative director at RBL Institute, a human resources think tank based in Provo, Utah. “That’s erroneous. We made the mistake 20 years ago of thinking that India and China would always have subordinate economies to the US, and look what happened.”

Brigitte Schmidt Gwyn, senior director of congressional relations at the Business Roundtable in Washington, DC, agrees. Outside of business strategies, the government needs more competitive policies to assist multinationals on the trade front, she says. “We can’t sit on the sidelines; we have to engage with the rest of the world,” she says. “In order to double our exports, as the President has proposed, we need a full range of policies that will make our companies, and our workers, more competitive. Trade is among them, as are education, training, tax policy and others. We need to have strong US multinationals who are well positioned to be as competitive as possible.”

Best Ways to Compete

The shift that is already under way and is likely to accelerate over the next 40 years will be immensely challenging for US-based multinationals. However, there are plenty of strategies companies can adopt in order not to fall under the wheels of the emerging markets trade juggernaut. According to Dadush, one of the most important strategies is to ramp up innovation. In order to successfully fend off competition from companies in developing countries, US-based multinationals must increase their ability in innovation and product differentiation, he says. “The success of developing countries in manufacturing will force rich countries to accelerate the pace at which they innovate and differentiate, as well as require them to make their business environment more flexible and predictable,” he believes. “Private investments in specialized skills and R&D; are likely to increase in importance, and governments can support the trend in various ways.”

US-based companies also need to continue to be vigilant about cutting costs while maintaining the current high quality of the goods and services they produce. “The US still has competitive advantages and can maintain those advantages if we continue to produce and export high-quality goods,” says Howard Schweitzer, an attorney at Cozen O’Connor in Washington, DC, and a former senior vice president at the US government’s export credit agency, the Export-Import Bank. “I’ve traveled around the world to a lot of these markets, and there is still significant appreciation for the quality advantage that the US has over goods produced in emerging markets,” he adds.

David Spooner, an attorney with the Squire, Sanders & Dempsey law firm and a former US assistant secretary of commerce for import administration, says another important factor is to hire locally. “The key is to hire and promote local talent and to use local consultants, and many large US companies do quite well in this respect,” he says. “Where the US can do better is at the level of small and medium-sized companies, which often look to remain within the slower-growing US market and don’t have customs expertise or language skills to do business abroad.”

Maintaining a competitive advantage also entails protecting your intellectual property—something US firms all too often neglect to do, the University of New Haven’s Haley says. “The competitive advantage of US companies is not in labor costs, it’s in technology, but too many companies risk their competitive advantage, their technology, overseas,” he says. “In markets like China there is a tremendous amount of intellectual property theft, so you are basically giving it away, and then you complain about the theft afterwards.”

According to Haley, companies that want to manufacture products overseas do not necessarily have to send their valuable proprietary technology overseas, too. If they do, they are placing their competitive advantage at risk.

Think Globally

As well as protecting their own technological advantages, companies will also need to be more creative with all their products and services, even those that are not designed for export. By collaborating with companies in other countries that are employing new techniques and technologies, RBL’s Younger says, companies can continue to improve all of their products and services. “You’ve got to think globally about your markets, about your technologies, about your partnerships and about every aspect of your business,” he explains. “Whether you’re a little company or a big company, it doesn’t matter. The world has gotten too small for us not to think about our businesses in global terms.”

While a few years ago outsourcing was seen as a panacea for remaining competitive, many companies have found it is not an instant fix for the bottom line. In fact, it can backfire, actually increasing costs, Haley says. While China’s labor costs may be one-twentieth of those in the United States, he points out, US labor is significantly more productive, which reduces outsourcing’s appeal. Add in the potential for major supply-chain problems, and there is no guarantee that outsourcing is going to improve profitability.

Haley’s final word of advice is to streamline decision making. “Most emerging market multinationals, whether they are publicly held or not, are still managed like family businesses,” he continues. “They act very, very quickly. So sometimes that leads to undesirable consequences, but usually it leads to them being able to move into a market as a first-mover and grab the first-mover advantage.”

The lesson for US-based companies? “Speed up your decision making and the ways you determine your strategy and how you implement it,” Haley advises. “If you don’t, you’re going to be losing in market after market.”

Source: The Transformation of World Trade, published by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace