In From The Cold

Global businesses and investors are taking more interest in sub-Saharan Africa, home to some of the world’s most neglected emerging markets.

By Antonio Guerrero

Sub-Saharan Africa has long been considered to be on the far frontier of the world’s emerging markets, but a recent flurry of activity suggests that many of its economies may be appealing to more mainstream investors. Senegal’s debut eurobond issue late last year, for example, put sub-Saharan Africa back on the radar for international investors. The deal also prompted several of Senegal’s neighbors to consider bringing issues of their own to market this year.

However, a return to capital markets will also shine a spotlight on the region’s many pitfalls and opportunities ahead. The five-year Senegalese issue, led by Citi as sole bookrunner and Standard Bank as joint lead, raised $200 million to partially finance toll-road construction. It marked the first time since 2007 that a sub-Saharan issuer came to market. Gabon launched a $1 billion, 10-year deal in December 2007, which followed Ghana’s $750 million, 10-year issue three months earlier. Senegal priced its issue at a high 9.25%, compared with Ghana’s 8.5%.

Kenya had postponed a bond issue amid the recent global financial turmoil. Nigeria announced plans to revive a $500 million issue this year to finance its $10.4 billion (4.8% of GDP) budget gap. Angola also wants to raise $4 billion, which would make it sub-Saharan Africa’s largest-ever eurobond issue. With investors hunting for yields, and with the region poised for growth, conditions are increasingly favorable.

Yet some analysts say countries will continue to depend on multilateral lenders. “For the most part, governments in sub-Saharan African countries will continue to rely on development finance institutions [DFIs], such as the World Bank, African Development Bank, European Investment Bank, for external financing,” says Pierre Yourougou, associate professor of finance at Syracuse University’s Whitman School of Management and an Africa business specialist. “Private sector companies will also continue to seek funding from DFIs,” he says. “The participation of these DFIs in private sector projects is viewed by other co-financiers as a guarantee and facilitates the mobilization of funding from international capital markets.” He adds that companies are also getting global capital markets funding through foreign partners.

“The improvement in the investment climate and the growing series of notable business successes explain the spectacular growth in the size and breadth of Africa-dedicated private equity funds,” notes Yourougou. Citing data from the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), the professor says sub-Saharan Africa’s share of emerging market private equity funds is around 7%, compared with Latin America’s 8%. He predicts that multilateral loans will grow in absolute terms, though funding from private sector sources is expected to grow faster. “DFIs now understand that to achieve sustainable economic development, a strong and well-functioning private sector is needed,” he says.

While Yourougou says several sub- Saharan sovereigns are able to tap international bond markets, he also notes recent efforts to develop the region’s domestic markets. As examples, he points to the creation of the African Domestic Bond Fund by the African Development Bank, the launch of the African Financial Market by several DFIs to support domestic bond and equity markets, and the African Financing Partnership launched in 2008 to promote co-financing among DFIs.

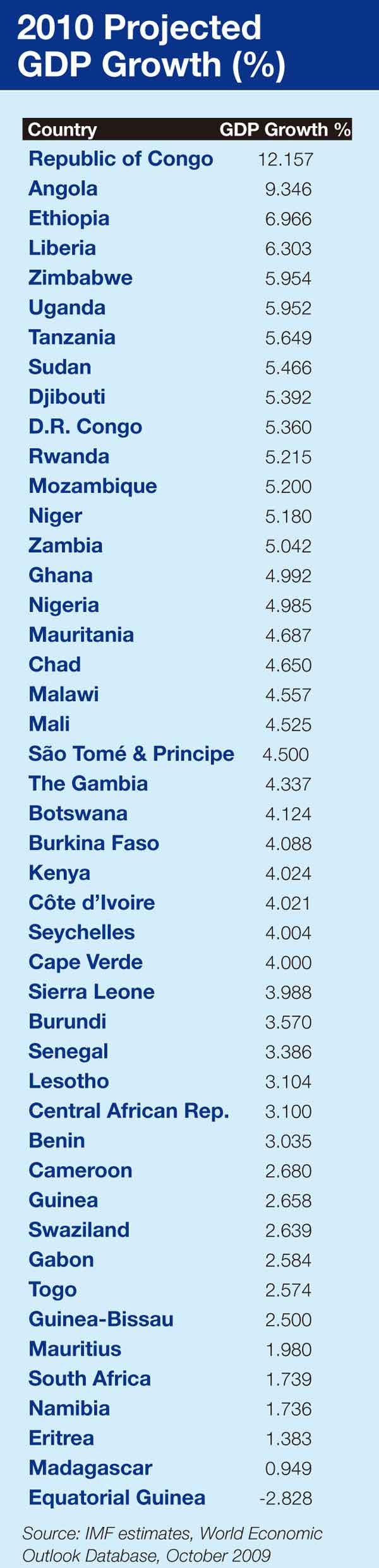

Not all sub-Saharan nations will be equally successful in raising financing or attracting foreign investment, with much riding on perceptions over their respective political and economic realities. The range is quite wide. At $242 billion, South Africa has the sub-region’s largest GDP. São Tomé and Príncipe has the smallest, at just $123 million. Equatorial Guinea has the highest per-capita GDP, at $7,470, but on the other end of the spectrum lies the Democratic Republic of Congo, with a meager $91. On the political front, governments range from established democracies to iron-fisted dictatorships.

“As long as you have significant human rights violations in some countries and lack of transparency in others, it will be challenging to attract foreign investment,” says Tom McDonald, a partner in the government policy practice group at the law firm of Baker Hostetler in Washington, DC. “For Africa to get the attention of the West on a sustainable basis, it needs to be its own policeman of failed states, promote free and fair elections, create better court systems and consistently enforce contracts,” adds McDonald, a former US ambassador to Zimbabwe. “Zimbabwe’s economic and political problems are certainly a liability for the region and a stain on the continent. When Zimbabwe is in the news for bad elections, killings, harassments, beatings and starvation, it of course becomes an impediment to investments elsewhere on the continent,” he says.

McDonald still recommends investors consider opportunities in Mauritius’, Angola’s and Ghana’s service industries, Nigeria’s natural resources sector, Congo’s mining industry and Zambia’s tourism industry and in South Africa. He warns investors to stay clear of Zimbabwe and Sudan. “Down the road,” he says, “US companies that do not think about Africa as an investment destination will certainly be missing the boat, leaving the playing field to Europe and China.”

The New Colonialists

China has been making substantial inroads to Africa, providing financing for large-scale infrastructure projects, including the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China’s (ICBC) partnership with Standard Bank to provide an $825 million, 20-year loan and $140 million bridge financing facility for expansion of a major power plant in Botswana.

“China is playing an increasingly influential role in Africa, and there is concern that the Chinese intend to aid and abet African dictators, gain a stranglehold on precious African natural resources and undo much of the progress that has been made on democracy and governance in the past 20 years on the continent,” says Jeff Krilla, a senior managing director for public law and policy strategies at the law firm of Sonnenschein Nath & Rosenthal in Washington, DC. Krilla, a former US deputy assistant secretary of state for democracy, human rights and labor, notes that more than two-thirds of African nations have undergone democratic elections, and the African Union will not recognize governments coming to power through undemocratic means.

“Recent economic trends are showing Chinese investment in Africa shifting from large state-run or state-backed conglomerates focused on natural resource exploitation to small, non-staterun manufacturers going head to head with local African traders and manufacturers,” adds Krilla. “Protectionist sentiment for domestic industries has bred increased anti-Chinese sentiment, but ultimately Chinese light industry, new technology and access to capital should help African countries compete in the global marketplace.”

Infrastructure is a key area for investment. Matt Herbert, a master’s candidate at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, believes developing effective links between banks and telecom companies to expand mobile banking could be particularly effectual. Herbert says mobile services help banks reach unbanked populations by reducing the cost of providing financial access. “In Kenya there has been sharp antagonism between the two industries, driven by banks’ perception that the telecoms are muscling in on their turf,” he says. “However, telecoms really aren’t structured to offer the sort of full-spectrum financial services that will make mobile financial services a transformative service for most Africans.” According to the World Bank, 17.5% of people in sub-Saharan Africa are mobile-phone subscribers, while only 1.6% have fixedline phones.

Banks Share Responsibility

Banks have a role to play in the subregion’s development. According to Sam Owori, CEO of the Institute of Corporate Governance of Uganda (ICGU) and former executive director of the African Development Bank, banking reforms are needed. “It is not helpful to design products and solutions that will cater to 5% of literate senior employed citizens when 70% to 80% of the economic activity is in the informal sector, and in the micro and very small scale but with the potential to graduate from the micro to small and from small to medium scale enterprises,” he says. “The commercial banks have been in Africa for over 100 years, yet their impact is minimal, their depth and width of coverage is pathetic, and their borrowers tend to be the same, year in and year out.”

“The banking statistics vis-à-vis national populations are pointed indictments for banks, considering the years they got away with traditional and nonchallenging operations in their comfort zones,” adds Owori, who says banks traditionally made profits and paid taxes but were lax in taking initiatives to expand their reach. Owori says borrowers are often at the mercy of lenders, as demonstrated by the large spreads of 5% to 20% between deposit and lending rates. “The indictment goes equally to the laissez-faire attitude of the African governments, which could have demanded more as a qualification forlicensing.”

Owori proposes that regulators impose maximum lending rates by industry and sector, after allowing room for fair returns. He also recommends setting minimum deposit rates to encourage savings and, in turn, provide funds for lending. Owori feels governments should do their part to make credit available and affordable, including “creating a conducive environment for business, reducing risks and costs in business, [providing] low taxes and tax holidays, promoting a proliferation and diversity of service providers, efficient infrastructure and utilities, effective supervision and regulation of the financial sector and generally promoting transparency, accountability, ethical behavior and responsible management.”

Although Owori’s recommendations appear ambitious, Mike Eldon, a business consultant in Kenya who writes a weekly column for Nairobi’s Business Daily, has others to add to the list. “[Governments] must reform themselves, becoming leaner and offering better public services,” he says. “Far too much of their revenues are merely spent on paying the salaries of ineffective bureaucrats, and that’s putting it nicely. They need to get a much closer and healthier [relationship] with the private sector, both in terms of formulating enabling policies and in creating far more public-private partnerships that benefit from the impatient, results-based business culture.”

Despite the challenges, Baker Hostetler’s McDonald argues there are opportunities available in the region, though only to those who do their due diligence correctly. “There are some good investments in sub-Saharan Africa, and the rate of return could actually be higher than in other parts of the world,” he says. “But you need to do your homework and be patient. Most importantly, you need to get on the ground and figure out the situation for yourself. This is not something that you can do through teleconferencing and the Internet.”