EMERGING MARKETS FOCUS: CENTRAL & EASTERN EUROPE

For most Central and Eastern European countries, 2009 turned out to be every bit as bad as expected. The region’s prospects for the coming year are mixed, at best.

By Justin Keay

In 1989 the fall of the Berlin Wall precipitated communism’s collapse and the start of the long transition toward democracy and free markets. Twenty years later the region finds itself embroiled in a less dramatic but still profound upheaval, as its governments and people struggle with the worst downturn since the transition began.

In 1989 the fall of the Berlin Wall precipitated communism’s collapse and the start of the long transition toward democracy and free markets. Twenty years later the region finds itself embroiled in a less dramatic but still profound upheaval, as its governments and people struggle with the worst downturn since the transition began.

Almost everywhere—in central Europe, the Balkans, Baltics and the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS)—the picture is brutal. “The region is suffering the worst economic decline since the early 1990s, [and] the crisis is not over. We are still seeing increases in non-performing loans and unemployment,” says Erik Berglof, chief economist at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

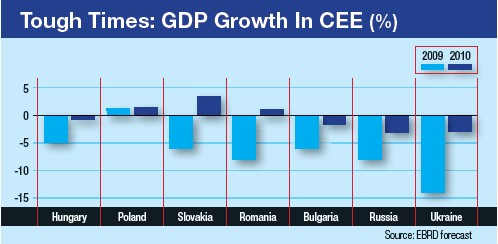

Indeed, the situation has deteriorated so far that the bank has had to adjust—downward—its forecast for 2009 three times. According to the latest, published in mid-October, GDP across the region will contract 6.3%—a steeper decline than the EBRD’s May forecast of negative 5.2%. Within this, while central Europe will see only a 3.4% decline, certain places are expected to fare much worse: Russia is expected to see GDP contract 8.5%, and Ukraine and Armenia 14% and 14.3%, respectively. Only Poland, Albania and some of the energy-producing CIS countries are expected to experience any growth at all.

So against such a backdrop, what does the future hold? The good news—that recovery will start to take place next year—is mitigated by the warning that it will be patchy and fragile, and dependent on recovery in the region’s main source of trade and investment, the European Union. “Put simply, if there is no rebound in Western Europe, there will be no rebound in Eastern Europe,” Berglof warns, saying that the recovery phase—whenever it does come—will be “modest.” Over the longer term he anticipates that one major consequence of the crisis is that average growth rates will be rather lower than before, which will lengthen the region’s economic convergence with Western Europe.

Berglof argues that the crisis was made worse by the large role foreign banks played in fueling the asset bubbles that burst in the Baltics and elsewhere. The banks also contributed to the huge foreign exchange exposure—and high personal debt—now prevailing almost everywhere across the region. Now, despite the recently reinvigorated loan efforts of multilaterals such as EBRD and the World Bank, the region’s mainly foreign banks will be highly risk averse, even as recovery starts, because of their existing over-exposure to bad assets. This will make it tough for small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs) and others to access capital—and will complicate recovery.

Similarly, although investor appetite for emerging market debt has returned, it has done so at a price. Hungary’s successful return to the international money markets with its €1 billion bond issue in July came with a 6.75% yield, almost double that of last year. A recent Lithuanian bond issue told a similar tale, despite being massively oversubscribed (reflecting perhaps the recent shortage of emerging market debt issuance).

Expect more of the same when Russia dips its toe back into the market, as it is expected to, with reports it plans to raise $18 billion on international capital markets early next year, to plug deficits made larger by the fall in oil prices over 2009 relative to the preceding year.

“One of the most evident changes this year is the sense that the region is a risk rather than an opportunity,” says Jon Levy, who covers Eastern Europe economies for the Eurasia Group, a consultancy.

This seems clear, even though emerging market sovereign bond yield spreads over US treasuries have been falling steadily over 2009. Analysts say it will be some time until they drop back to pre-crisis levels, which is a major concern given that in the wake of the crisis many countries are going to need lots of capital. Russia, for example, may seek to raise as much as $80 billion over the next three years.

For this reason the Eurasia Group suggests that privatization will be a big feature of 2010 and beyond, as governments take advantage of slowly improving investor sentiment and sell assets to raise much-needed cash. In late October Poland announced plans to sell €8.9 billion of assets over the next two years; the budget deficit is around 6% of GDP while public debt has risen to around 50%, close to the ceiling mandated for ERM-2, the waiting room for euro membership. Other countries can be expected to follow its lead.

Many will also prioritize foreign direct investment, which has suffered a massive fall-off. For EU countries and candidates, structural adjustment and cohesion funds will mitigate some of the FDI shortfall, particularly in the poorer regions that may not have attracted it anyway. The EU has earmarked some €347 billion in such funding up to 2015.

However, the countries will also have to start publicizing less obvious investment opportunities in a bid to boost overall growth. “The region’s proximity to Western markets, its skilled workforce and improving infrastructure means there are lots of opportunities aside from the hitherto obvious areas of finance and real estate,” says Levy.

Another likely change is that any concerns about joining the euro will now be put aside. Hungary and others that experienced foreign exchange crises have firsthand experience of how tough it is to survive in a globalized world with a small currency. As a result, many central and east European countries will publish road maps for membership as soon as possible.

As central Europe attempts to pull itself out of the mire, it is worth noting that its less steep decline compared with eastern Europe reflects its strong integration into Western political, financial and economic structures, which sustained confidence and activity when this was most needed. The strong policy response of the international community—for example, providing support to Hungary, Romania, Serbia and Bosnia—also played a significant role in mitigating any greater collapse.

“When the crisis first hit in October 2008, we went simultaneously to the EU and IMF, and we are very thankful for their support,” says Gordon Bajnai, who became Hungary’s prime minister in April and has since committed his country to the tough reforms it previously eschewed.

As countries grapple with the next phase of the crisis, one can only wonder what might have happened if international support had not been forthcoming in the first phase.

Baltic Battles

Even by t he grim standards of 2009, the downturn sweeping through the three Baltic states has been bewildering in its extent and severity. Before the economic tsunami hit in autumn 2008, Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania were enjoying annual growth rates of between 7% and 10% as money poured into real estate, construction and tourism. Tallinn, Riga and Vilnius became boom towns as people fell over themselves to buy apartments and as Western investors competed to open the next luxury hotel, restaurant or store.

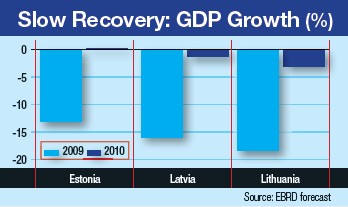

Today, all that remains are the cruel statistics showing how this was largely built on sand. According to the IMF’s latest World Economic Outlook, GDP in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania this year will contract by 14%, 18% and 18.5%, respectively. Trade has fallen off a cliff. Eurostat, the European Community’s statistics office, says the Baltics are experiencing the steepest reduction in the EU: Over the first seven months, trade volumes contracted 35% compared to the same period in 2008.

“These figures reflect the bursting of a real estate bubble fueled by the easy credit extended by Western banks,” says Jon Levy, East Europe analyst with the Eurasia research group.

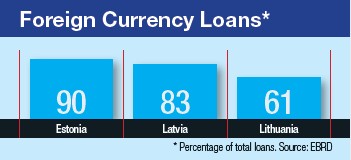

For the Baltics, all rocked by the crisis, the problem has been rendered more complex by fixed exchange rates. Latvia’s currency peg and the currency boards in Estonia and Lithuania were designed to bolster stability and ease entry into the eurozone, and all joined ERM-2, the necessary first step. However, the currency boards’ existence encouraged consumers to take out foreign loans at rates often lower than those available for loans denominated in lats, crowns or litas. The extent of this currency risk (see graph, right) makes devaluation almost suicidal, even if the Baltic states could weather the loss of international confidence it would also engender.

This has left policymakers with only fiscal weapons, which, given the battered public mood, they have unsurprisingly been reluctant to fully employ. If they do not deploy them, though, international support may well be halted.

Latvia is a case in point. Despite assurances to the IMF and EU that were a condition of its €7.5 billion rescue last year, Riga has failed to implement sufficiently large spending cuts and has seen payouts delayed as a consequence.

Despite this, Levy argues the Baltic crisis is a European rather than a classic emerging market crisis, because of the limits to the downside. “At the end of the day, the EU is committed to preventing these countries defaulting and to them eventually joining the euro,” he says.

The big concern remains a devaluation by Latvia, which would have major repercussions for the other two nations and for the Swedish, German and Austrian banks with high exposure to the region. Even without a devaluation, Moody’s recent Banking System Outlook expresses concern over private sector and household debt and the banks’ continuing large exposure to real estate and SMEs; it warned that the banking systems probably have not reached the bottom of their respective downturns.

This is because the contraction is not over: For 2010 the IMF predicts a 2.6% decline for Estonia and 4% for Lithuania and Latvia, with growth returning only gradually in 2011, when Estonia hopes to join the euro. Even then, GDP is expected to grow at rates closer to 4% rather than the 8% to 9% that prevailed before. “Given the unsustainability of growth before, perhaps this shouldn’t be seen as a bad thing,” says Agata Urbanska, analyst with the ING Group in London.