DOWN BUT NOT OUT

Central and Eastern Europe was arguably the region hit hardest by the global downturn. It’s still suffering, but hopeful signs are clearly emerging.

By Justin Keay

It wasn’t meant to be like this. According to the original script, Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) was to have celebrated the 20-year anniversary of the fall of communism this year with unalloyed enthusiasm. The countries would look back on how they built competitive, successful free market economies and attained NATO and EU status—with Slovenia and Slovakia also benefiting from eurozone membership—and consider how they were increasingly making their mark on the world stage. Former Polish premier Jerzy Buzek’s becoming president of the European Parliament would be the latest proof. In short, 2009 was supposed to be all about how CEE was becoming increasingly indistinct from the Western Europe it has long sought to catch up with.

All of that is true, but the celebrations will be muted. “Contrary to how things looked when the financial crisis and economic downturn started, this has been the hardest hit of any emerging market region, possibly of any region—period,” says Charles Robertson, head of emerging markets research for ING Barings in London.

In most countries of the former communist world, free market concerns like recession, increased bankruptcies and growing unemployment are the new reality. Relatively fragile political systems have struggled, with new governments emerging from the economic rubble in Latvia, Hungary and Bulgaria, to name just three. Croatia’s respected premier Ivo Sanader stepped down midway through his term in early July without explanation, overwhelmed by Croatia’s worsening economic crisis and faltering progress in its EU application.

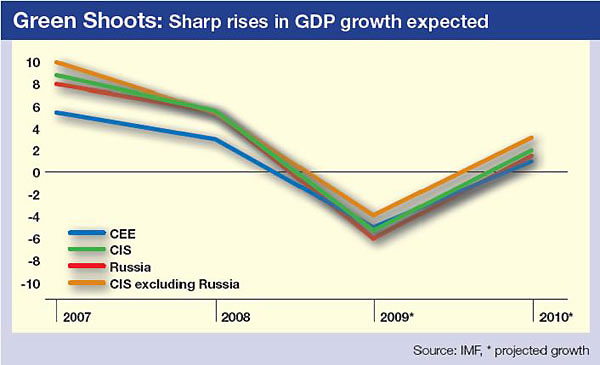

Meanwhile, each latest report the International Monetary Fund releases grows more pessimistic. After forecasting in April that GDP this year would contract 3.3% across CEE (with growth recovering to an anemic 0.8% next year), its latest report sees growth plunging by 5% (albeit with 1% growth in 2010), with the Baltics, Ukraine and Hungary all faring much worse than average. Only Poland has any reasonable chance of growth this year.

“CEE faces a particularly severe credit liquidity tightening environment because it hasn’t had the policy response tools available to Western governments,” says Jon Levy, analyst with the Eurasia Group, an international consultancy. “Monetary policy is constrained because lowering interest rates would devalue the currency and increase the cost of foreign-currency debt,” he adds.

The region’s problems are, in part, a reflection of its success in opening up to the world, much of which is now also deep in recession. Its once-closed economies are now among the world’s most open, with Hungary, the Baltic States, the Czech Republic and Slovakia all having trade-to-GDP ratios of over 80%. Poland, the largest and most self-sufficient economy, has the lowest ratio at around 40%. By comparison, India’s trade-to-GDP ratio is just 10%, Brazil’s 15% and China’s 35%. Trade openness was accompanied by high dependence on foreign capital flows, which before the global downturn kept the region’s economies moving forward. Financial institutions from countries such as Austria, Germany, Sweden and Greece own most of the banks and were happily lending—usually in euros—to local businesses and consumers.

This, like much of the trade flow, all came to a sudden, shuddering halt in the fall of 2008 and has yet to resume, despite the efforts of the IMF, EU and other multilateral bodies to keep funds flowing. At the same time, local currencies have plunged, increasing private and public debt levels to worrying new highs. The IMF has warned that CEE could experience problems in rolling over the $413 billion in external debt due to mature over 2009, especially given that many countries also need to finance large current account deficits as well. In April the IMF suggested the financing gap could reach $123 billion, with a further gap of $63 billion opening up next year.

With governments struggling to contain growing deficits and keep their economies afloat, most bets about joining the euro within the foreseeable future are off. Poland, which had hoped for 2012, has now admitted that looks unrealistic, given the fiscal situation, the downturn and currency instability. The earliest possible date is now 2013, with 2014 more likely. The Czech Republic’s traditional ambivalence has deepened amid concerns the euro could act as a straitjacket on growth, while Hungary’s enormous external debts and other problems suggest 2015 at the very earliest. Nobody wants to estimate entry dates for the Baltics or the Balkan states, despite the former having already fixed their currencies against the euro.

Investor Confidence Dented

“Foreign direct investment [FDI] will fall across the region,” predicts Matteo Napolitano, a Central Europe analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit, adding that even when the dust settles, maybe by 2011, growth prospects look uncertain and certainly not “as rosy as pre-crisis.”

All is not so bleak, however. The nightmare scenario of CEE’s problems bringing down a major bank and precipitating a financial domino effect has not been realized. There are still concerns about individual banks, such as Hungary’s OTP, which despite having extended into Bulgaria, Slovakia and Romania felt obliged to pull back from a merger with Poland’s PKO BP.

“The financial leg of the crisis has troughed—there is no longer much talk of Western parent banks withdrawing capital—and the sector should soon begin to regain stability,” says Napolitano, although he adds that new lending will be sluggish and the financial sector may see further consolidation.

The decision by the Group of 20 to substantially increase funding and support for the region’s banks in particular did much to bolster stability. And the reality is that the CEE region’s loans-to-GDP ratio is still relatively low at an average of 100%—compared with 250% in Western Europe—despite the massive boom in bank lending in the two years leading up to fall 2008. In Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia the ratio is even smaller—between 40% and 50% of GDP—suggesting that once the crisis passes, the countries have the capacity to take on more debt to finance further growth.

And despite the gloom, the region still has much to offer investors. “This is not a wasteland but a region undergoing integration with the EU that will also eventually be using the euro,” Levy points out. He stresses that low labor costs, the major ongoing upgrading of infrastructure (such as roads, ports and railways), much of it funded by EU structural funds, and CEE’s proximity to key markets make this a highly competitive region by any standard.

It is also worth keeping in mind that despite the dramatic falls in output recorded by some countries, 2009-2010 will not be as bad as the early 1990s, when transition started and many economies lost up to half their worth. “One needs to keep a sense of perspective,” says Robertson. “Despite the crisis, all of the countries of the region will still be richer at the end of 2009 than they were at the end of 2006.”

So it may not be such a dismal 20th anniversary after all.

|

Amid a generally discouraging picture, where are Central and Eastern Europe’s brightest and darkest spots?

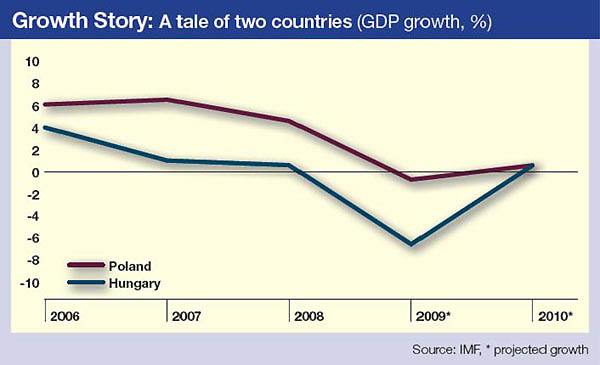

Among the winners, Poland stands out, with a stable banking system, generally low levels of debt, a cohesive, effective government and some prospect of growth—though not much—in the annus horribilis that is 2009. The Czech Republic and Slovakia, though they have suffered economic contraction reflecting a heavy dependence on auto manufacturing, also deserve an honorable mention: Policymaking has been consistent, and banks are well capitalized. Although unemployment has risen in Slovakia to around 15% (on the back of a 11.2% contraction in GDP between January and April), membership of the euro has meant there is no currency risk, which is one reason why VW chose it over the Czech Republic for its new $435 million plant to build the company’s new family car.

Among those suffering worst, all three Baltic states, but particularly Latvia, deserve special mention. Major real estate bubbles have burst, while the massive expansion in credit that gave these economies unsustainable growth rates up to 2008 has completely dried up. At the same time, unprecedented wage increases have made the economies uncompetitive. Meanwhile, exchange rates pegged against the euro have robbed policymakers of a vital tool, even while they fought to prevent further deteriorations in confidence and increases in foreign debt. The IMF believes Latvia’s GDP could contract by 18% this year, leading the multilateral’s representative in Riga to comment, “Latvia is in for an incredibly tough year.”

Hungary, for so many years the darling of foreign investors in CEE, has also fallen hard. Its problems include sluggish growth, huge external and fiscal deficits and private sector foreign-currency over-gearing compounded by political near-paralysis and a continuing failure to get a handle on such problems as a large, costly and inefficient public sector and an unreformed, bloated pension system. ING Barings reckons GDP will shrink by around 6.5%.

Romania and Bulgaria continue to be blighted by corruption, lack of transparency and huge, inefficient public sectors as confirmed by the EU’s latest progress report, published in late July. Bulgaria’s situation has been made more parlous by the collapse of the real estate and construction boom, which at its peak accounted for almost one-third of GDP growth. GDP contraction, however, may not be as bad as elsewhere: The new government in Sofia projects a 2.5% contraction for 2009 against the 6% decline for Romania predicted by its economy ministry.

Further east, things look even grimmer. Moldova, as ever, is struggling for its very viability as a nation in the wake of continuing GDP declines and political crisis. Ukraine, defined by one analyst as “an economic disaster zone which has done almost nothing to help itself in the current crisis,” expects GDP to contract by up to 20% on the back of major falls in demand for steel, its single biggest export. |