REGIONAL FOCUS ASIA

Asia’s economic powerhouses are shifting to a new economic model. The transition will be painful—but will also pay huge dividends.

By Thomas Clouse

Asia has played a starring role in the story of globalization. The region has pulled in massive foreign investment and found eager markets for its products around the world. The region’s exports now range from simple consumer goods to sophisticated electronics and popular automobiles. The strong investment and booming exports have given Asian economies some of the fastest growth rates in history, and Asia now boasts the world’s second- and third-largest economies, in Japan and China.

Asian policymakers, drawing from the lessons of the Asian financial crisis a decade ago, managed their countries’ successes conservatively. They kept budgets low, limited external financing, pursued conservative monetary policy and built up substantial foreign exchange reserves. They also pushed forward aggressive financial system reform, greatly strengthening banks and other financial institutions.

All of these moves have cushioned the impact of the current global economic crisis. Asia’s regional economy maintained relative stability as global liquidity tightened, and policymakers were able to lower interest and reserve rates while introducing fiscal spending programs. In addition, Asian banks had only limited exposure to mortgage-backed securities. Australian financial services firm Macquarie Group estimates the region’s total subprime losses at less than $35 billion, accounting for 0.2% of total bank assets. Bill Belchere, chief Asia economist for Macquarie Group, says, “From our macro perch, Asia has proven well equipped to maintain financial stability since the onset of the global recession and credit crunch by virtue of its both … high level of FX reserves relative to short-term external debt and sustainable current account positions with low non-performing-loan levels.”

Belchere warns, however, that the strong financial positions of Asian countries cannot compensate for the long-term problems with the region’s growth model. “One of our key macro themes for the first half of 2009 remains the struggle between Asia’s strong macro balance sheet and its impaired growth/business model,” he says.

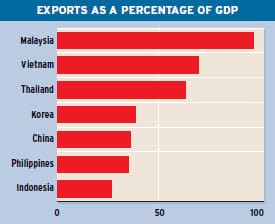

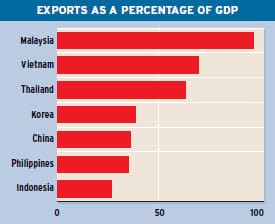

The impaired growth model to which Belchere refers has served Asia well in the past. The model fuels economic growth primarily with export increases. But with the United States, the European Union and Japan now in recession, demand for Asian exports has dried up. Thus, despite Asia’s strong financial position, the real economy is beginning to suffer due to its dependence on these export markets.

“Given the linkages to the rest of the economy reflected in the high export-to-GDP ratios,” Belchere continues, “the indirect impact on the non-tradable sectors will be considerable. And if the business model freezes up, then the strong balance sheet will deteriorate.”

Recent export and GDP numbers already show signs of this deterioration in the macro economy. China and India both registered drops in shipment volume of more than 15% year-on-year. For Japan, Korea and Taiwan, which tend to export more expensive products, the drop was even more severe, ranging from 34% in Korea to 46% in Japan.

Falling exports led the International Monetary Fund (IMF) in January to revise down growth estimates for 2009, with developing Asia expected to grow 5.5%, down from 10.6% in 2007 and 7.8% in 2008. Asia’s newly industrialized economies (NIEs) will shrink by 3.9%, and Japan’s economy will contract 2.6% in 2009, the IMF predicts. In comparison, Asia’s NIEs grew by 5.6% in 2007, and Japan posted growth of 2.4%.

These recent statistics, however, show only one aspect of the crisis. Eduardo Chakarian, principal of the Singapore office of management consulting firm Monitor Group, explains: “All crises have two aspects—short-term turbulence and the world after the crisis. A crisis comes to correct some distortions in the market, and so the world after a crisis will never be the same world as before a crisis.”

The distortions to which Chakarian refers relate to the trade imbalance between Asia, especially China, and Western markets, the US in particular. That trade imbalance provided inexpensive credit from Asia to consumers in the West, allowing them to buy products from around the world and fuel export booms for many Asian economies. The current crisis is still in the short-term-turbulence phase. Asia may have even more challenges waiting in the world that emerges afterward.

Economics professor Willem Thorbecke of George Mason University and RIETI (the Research Institute of Economy,Trade and Industry in Tokyo) compares the relationship between the two primary contributors to this imbalance, the US and China, to a couple in an unhealthy relationship but unwilling to break it off. “This [imbalance] led to extreme outcomes,” he says, “with a very poor country like China consuming less than 40% of a low income and a very wealthy country like the US consuming more than 70% of a very high income.”

The imbalance is not healthy, nor is it sustainable, Thorbecke believes. “Just like a couple that breaks up, if China and the US break off this relationship, there will be pain for both sides. But as long as the transition is orderly, it would be good for both countries.”

To make this transition, Thorbecke suggests that Asian governments offer more support for the service sector, giving priority to investments in education, healthcare, environmental protection, pension funding and research. Such support helps on two fronts. First, service-related industries generally employ more people than capital-intensive manufacturing industries. Second, education, healthcare and retirement costs are reduced for the consumer, freeing up more savings for consumption.

Several Asian countries have already begun trying to boost their service industries. Stimulus packages in China, Malaysia and India pledge some form of support for education, healthcare and/or labor-intensive industries. Stimulus plans in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan employ various tools to spur domestic spending. Many of these countries, however, have yet to release the full details of their spending plans.

These investment packages also include provisions for greater investment in physical infrastructure and assistance for manufacturers. Such investment will help weather the short-term turbulence but may not be as helpful for long-term change. Infrastructure investment will facilitate future economic development in China, for example, where such structures remain underdeveloped, but will be less effective for long-term growth in Japan, where strong infrastructure already exists. Thus, the proper allocation of stimulus money will be essential for sustainable benefits.

Regulatory changes will be equally important. Incentive structures in most Asian countries favor manufacturers. China’s rigid exchange rate policy offers one prominent example. The Chinese yuan’s exchange rate, which is managed by the government, increases the price competitiveness of Chinese exporters but reduces the buying power of Chinese consumers. Taxation and investment policies in Asia also tend to favor manufacturers. Adjusting these incentive structures would help correct the imbalances that feed Asia’s export dependence.

A Painful Transition Looms

Most economists and policymakers probably would agree that Asia could benefit from more domestically driven economic growth, but the transition from its current growth model will not be easy. Tom Byrne, a senior vice president at ratings agency Moody’s, explains: “The export-oriented firms are the most productive and profitable, having subjected themselves to global competition. There would need to be a reorientation in market focus and product mix. Emerging markets may have insufficient market size or income levels to substitute for the loss in global markets.”

Greater intra-regional trade could help alleviate some of these problems, especially for Asia’s smaller countries, which do not have market size to support domestically driven growth. The recent summit of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) offers some signs of movement in this direction. The group of 10 countries agreed to form an integrated economic community by 2015, similar to the European Union but without a common currency. While challenges remain, in terms of wealth discrepancies in particular, the Asean community could eventually provide substantial opportunities for its members to build off each other’s strengths.

Japan, China, Korea and Asean have all been active in pursing markets outside of Europe and the United States as well. Asean signed a free-trade agreement with Australia and New Zealand last month, and Japan and China have both sought trade agreements with South American countries. Monitor Group’s Chakarian explains the rationale behind such agreements: “Instead of everything going through the US and Europe, developing countries can create a sustainable market, with products and information flowing between China and Brazil, India and other emerging economies. In this way, they can significantly reduce their dependency on the developed economies. This crisis, which originated in the so-called developed world, will foment that movement.”

Stronger domestically driven demand, increased regional integration and expansion into new markets can all help Asia to prosper in the long run. But ultimately, the exceptionally high growth rates achieved through Asia’s export-oriented growth model will be tough to duplicate. Moody’s Byrne puts it simply: “The implication is for slower long-term growth, whether an economy becomes less export dependent or not.”

If long-term growth will be slower in any scenario, one might wonder why Asia should take steps to move toward domestically driven growth. Ultimately, though, it is the people of Asia who would benefit most from rebalancing the region’s growth. By keeping money at home, rather than sending it overseas, Asia can invest in its own development. And as the service sector develops, more money will go toward wages, boosting living standards and buying power.

A December report by the Asian Development Bank emphasizes the need for such adjustments, regardless of the global economic situation: “The global financial crisis has not created the need for developing Asian countries to rebalance their economies. What the crisis has done is add a much needed sense of urgency to a need that was already there. More balanced growth is in the best interest of developing Asia’s own growth and development in the long run. The fact that it helps to mitigate global imbalances is a positive byproduct, albeit an important one, especially in view of current circumstances.”

This mitigation of global imbalances will reduce the buying power of Western markets. The implications for Asia are immense. The dazzling economic achievements of Japan, the Asian “tiger” economies and, more recently, China, India and the region’s other developing markets all grew from the region’s export-centered growth model. This model, however, has not only lost its traction in the current economic crisis but is unlikely to regain its economic muscle even when this crisis eventually passes.

For this reason, Asia needs a new economic growth model. Defining that new model and making the transition to it will be challenging, and the model will not be the same for all of Asia’s countries. But domestic demand, regional integration and new trade markets will be essential ingredients. The ongoing global rebalancing, complemented by the establishment of more balanced economic models, will allow the people of Asia to continue enjoying their leading role in the 21st century global economy.

Asia has played a starring role in the story of globalization. The region has pulled in massive foreign investment and found eager markets for its products around the world. The region’s exports now range from simple consumer goods to sophisticated electronics and popular automobiles. The strong investment and booming exports have given Asian economies some of the fastest growth rates in history, and Asia now boasts the world’s second- and third-largest economies, in Japan and China.

Asia has played a starring role in the story of globalization. The region has pulled in massive foreign investment and found eager markets for its products around the world. The region’s exports now range from simple consumer goods to sophisticated electronics and popular automobiles. The strong investment and booming exports have given Asian economies some of the fastest growth rates in history, and Asia now boasts the world’s second- and third-largest economies, in Japan and China. Stronger domestically driven demand, increased regional integration and expansion into new markets can all help Asia to prosper in the long run. But ultimately, the exceptionally high growth rates achieved through Asia’s export-oriented growth model will be tough to duplicate. Moody’s Byrne puts it simply: “The implication is for slower long-term growth, whether an economy becomes less export dependent or not.”

Stronger domestically driven demand, increased regional integration and expansion into new markets can all help Asia to prosper in the long run. But ultimately, the exceptionally high growth rates achieved through Asia’s export-oriented growth model will be tough to duplicate. Moody’s Byrne puts it simply: “The implication is for slower long-term growth, whether an economy becomes less export dependent or not.”