President Lula’s bold program of social and economic reform has become a model for economies in Latin America and beyond.

|

|

|

Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, has become the world’s most outspoken advocate of what some call “social capitalism,” a marriage between free-market policies and social spending. So far, his strategy has paid off as more of his compatriots emerge from poverty. While the recent global financial meltdown could put a damper on his social experimentation, Lula disagrees and says the pain unleashed by the crisis makes his social programs even more relevant.

Lula, a former street vendor, metalworker and labor activist, was first elected in 2002 under the Labor Party (PT) ticket, unleashing market jitters over what some investors assumed would be an administration dominated by traditional Latin American populism. Instead, he introduced business-friendly policies and embraced fiscal orthodoxy. While investors returned in droves and commodities prices soared, Lula used the windfall to fund a series of social programs that have not only improved living standards nationwide but also gained him an 80% approval rating among Brazilians. In his native Northeast, the country’s poorest region, his support rating is an astounding 92%.

“The central idea is that you can have a dynamic private sector that remains an engine for growth while also protecting the most vulnerable members of the population and helping those at the margins of the economy to get some of the fruits of economic growth,” says Leonardo Martinez-Diaz, political economy fellow at the Brookings Institution in Washington, DC. “It’s a very powerful economic formula.”

The most liberal members of the ruling PT have been less supportive at times, calling on the president to loosen the purse strings and abandon his fiscal conservatism. Lula, however, has resisted temptation and stayed the course, gaining him accolades both at home and abroad. Even the International Monetary Fund, with which Lula maintains a somewhat contentious relationship, has praised his administration for maintaining market-friendly policies, raising the primary surplus target to ease initial concerns over debt sustainability, pursuing structural reforms and taking steps to curb inflation. This year Brazil gained a coveted investment-grade rating for the first time.

Social Programs Pay Off

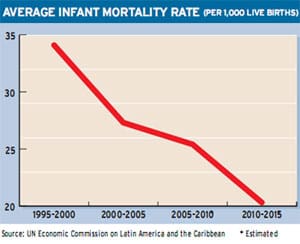

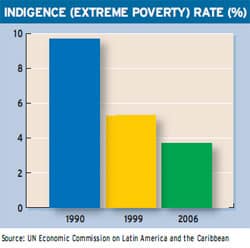

The results on the social front have been impressive. Chronic malnutrition among children under five years old dropped to 7% in 2006 from 13% a decade earlier. The drop was even more dramatic in the Northeast, from 22.1% to 5.9% during the same period. Infant mortality almost halved, from 39 deaths per thousand live births in 1996 to 22 in 2006.

One of Lula’s first social programs, called Fome Zero (Zero Hunger), includes a variety of measures, from family farming initiatives to providing free meals for students at elementary schools. Another key program, Bolsa Familia (Family Grant), is a cash transfer plan providing aid to 7.5 million poor families, with parents committing to keeping their children in school and getting them vaccinated, among other conditions. Aid payments vary according to income levels but are no higher than $100 per month.

While critics charge that the Family Grant program encourages joblessness, the administration counters that a higher $250 per month minimum wage is an incentive to get off the program and seek work, with 1.4 million families no longer qualifying for aid under the plan last year alone. The government recently tweaked the program’s guidelines to increase the age of beneficiaries to 17 from 15, removing an incentive for teenagers to drop out of school and seek work at 15.

“In Brazil you can do this fairly cheaply,” says Martinez-Diaz. “Bolsa Familia [Family Grant] is only 2.5% of all government transfers, including pensions. That’s a lot of political capital for very little money.” It is precisely this type of political capital that, Martinez-Diaz feels, will keep the programs running despite an expected economic slowdown amid global financial turmoil. “In the immediate future these programs are not in jeopardy because they’re a central priority of the Lula administration and they’ve managed to make a dent in inequality in a very visible way,” he says.

Lula himself has said there will be no cuts in social spending next year, despite official estimated forecasts of a slowdown in GDP growth from last year’s 5.3% to closer to 4% in 2009. Morgan Stanley is less bullish and predicts GDP will grow by a meager 2% next year, primarily due to falling commodities prices that will eat into export revenues. Brazil remains a major exporter of such commodities as oil, soybeans, iron ore, ethanol and sugar.

Despite the slowdown, Brazil’s economic fundamentals remain strong, and it faces little threat of an economic crisis, with more than $200 billion in foreign reserves providing a cushion. Lula is also counting on the development of new offshore oil finds believed to hold some 80 billion barrels of light crude, equal to more than four times the country’s existing proven reserves. While the new fields could require some $600 billion in investments over the next three decades, analysts say these may yield as much as $5 trillion. Lula has pledged to find ways to guarantee, even after his term ends, that a portion of the expected oil revenues is earmarked for social spending, particularly on education.

Some analysts say the only drawback is that higher financing costs and lower oil prices could dampen the outlook for developing the offshore oil finds that would allow Brazil to maintain its current self-sufficiency in oil and make it a major exporter. Petrobras, the country’s state-controlled oil company, plans to forge ahead with $163 billion in investments over the next five years, according to a report by Credit Suisse. “Petrobras decides its investments by looking at the long term,” Petrobras CEO José Sergio Gabrielli said at a recent summit in Houston, adding that he does not expect the global crisis to affect the company’s capital expenditure program.

Agriculture Adds To Balance

Agriculture is another sector where the Lula administration is linking economic development and social improvements. The National Program for Strengthening Family Agriculture, part of the Zero Hunger program, has boosted its subsidy to small farmers by 400% since 2003. By reaching some 8 million farmers, the program increases food production, boosts family incomes and halts the rural exodus to urban areas. A new bill in Congress would ensure that 30% of food for free elementary school meals is purchased from small farmers. Once the measure is approved, school meals will be extended to high schools, raising the number of beneficiaries to 42 million students.

Small farms employ 70% of Brazil’s rural workers and produce the majority of the country’s food supply, though occupying only 30% of the country’s cultivated lands. It is no surprise then that, as the country began feeling the impact of the global financial crunch, one of finance minister Guido Mantega’s first actions was to announce a $2.6 billion capital injection into the agriculture and construction sectors.

According to Pedro Seraphim, head of the energy practice at TozziniFreire, Brazil’s largest law firm, one initiative also links agriculture and energy. “There’s an important initiative in the Northeast for the production of biodiesel in which the government is motivating small farmers to produce oilseeds that can be easily grown in dry areas,” he says. “The idea is that producers will have guaranteed supply agreements with Petrobras, which will use the oilseeds to produce biodiesel,” he adds. Brazilian law, he notes, mandates the blending of 3% biodiesel per gallon of fuel, with ample biodiesel production now leading the government to consider upping the blend to 5%.

|

Brazil may not have been able to carry out such social investments under its previous IMF-mandated economic policy guidelines, which ended with the government’s prepayment of its debt with the multilateral. Martinez-Diaz says the IMF is not generally averse to social programs if they are well run and transparent. “When countries go to the IMF, they are already in a financial crisis, so the IMF comes in and looks at their budgets and often recommends cutting spending in social programs,” he says. “Brazil was fortunate that it could launch these programs when it was in good financial condition.”

“I think it’s clear that if the government needs to cut expenditures next year, it will not be in social programs,” says Sergio Goldman, head of equity research at Bulltick Capital Markets, a Miami-based investment bank specialized in Latin America. Goldman, who lives in São Paulo, says it is more likely that the government would slash public sector salaries than eliminate one of its political pillars. He also feels the administration will not significantly increase social spending under the current slowdown but may still increase infrastructure investments to spark growth and boost competitiveness, a move that could appease some of the president’s more radical PT colleagues.

Global crisis or not, it appears Lula’s social initiatives may outlast him. “It’s going to be very difficult for future governments to eliminate these types of programs because they are now part of the culture among lower-income sectors of the population who benefit from them,” says Goldman. Lula’s strong approval ratings may point to support from a broad socio-economic spectrum, though Goldman feels that the sheer number of lower-income families in Brazil will make it difficult for Lula’s successors not to provide them with relief.

|

That is not to say that Lula’s social initiatives have eradicated poverty and social inequality among the country’s population of 195 million. Much still needs to be done on many fronts. A study by Brazil’s IPEA economic research institute shows that whites still earn on average 50% more than blacks in a country where blacks make up half of the population. Another study by Brazil’s IBASE socio-economic analysis institute shows that nearly 21% of beneficiaries of the Family Grant program still suffer from food insecurity, defined as at least one family member going hungry at least one out of every three days.

Nevertheless, few would argue that Brazil is not moving in the right direction or becoming a model for other emerging markets tackling social ills. Lula would likely be the first to recommend that doing so while maintaining fiscal responsibility is the key to long-term success. While some of his Latin American counterparts may disagree with his strategy, preferring to ignore fiscal stability in favor of political gain, Lula has found the way to maintain both.

Antonio Guerrero