Central and Eastern Europe has transformed from a beacon of hope into a near basket case astonishingly quickly. Its recovery will be a far slower and no less painful process.

|

|

|

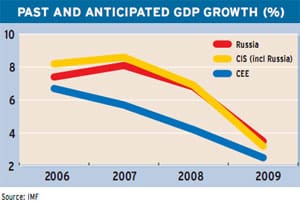

A newly confident Russia, basking in oil prices at $147 a barrel and similarly strong commodities prices, seemed poised for growth of 7% to 8%—marking the eighth year of GDP growth at around this level—with other fundamentals looking similarly healthy. President Dmitry Medvedev even spoke—perhaps rashly—of Russia becoming one of the lynchpins of a new economic order, with the ruble becoming a reserve currency and Russian oligarchs benevolently going to the rescue of Western banks and companies. Within the region, the Baltic states and Hungary seemed the only problems—the former suffering the fallout from a property/consumption bubble that took inflation and external deficits to record highs, the latter from years of overspending, high taxation and failed economic reform, which pushed foreign debt levels to among the world’s highest.

Today, across the board, the picture looks very much bleaker. “No country will be immune from the global slowdown,” says Peter Sanfey, economist for the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in London.

Others go further. “Things have turned bad much faster and much more extensively than anybody could have imagined,” says Charles Robertson, head of emerging markets for ING Barings in London. He says the bank has had to make radical downward revisions to its 2009 projections since July, with a 5.1% GDP growth forecast for Ukraine turning into 0.5% “at best,” Poland’s 5.1% becoming 3.5%, and Hungary’s hopes of attaining 3% growth being dashed by a revised forecast of -0.8%.

Although most observers still predict some GDP growth in Russia in 2009, confidence within and about the country has nose-dived, not helped by Moscow’s August invasion of Georgia that suggested earlier hopes of it behaving like a responsible member of the international community were premature at best. The collapse in oil prices to around $60 per barrel in early November and the 25% slump in commodities prices since July have revealed once again Russia’s dependence on the primary sector. Capital flight is at near record levels, and prices on Russia’s stock markets have dropped 75% since the start of 2008.

Rather than bailing out Western entities, as Medvedev wishfully predicted, oligarchs have been obliged to turn to the state for help in meeting their financing requirements. The failure to further develop manufacturing or services outside the big cities during the high-growth years of 2000-2008 means recovery will be slow and overly dependent on oil and commodities price movements.

Ukraine’s experience, meanwhile, suggests that the healthy growth of recent years was built largely on sand. With metals accounting for some 40% of exports, the drop in global prices has left its economy heavily exposed, despite the benefits of cheaper oil and gas. Few were surprised that Kiev turned to the International Monetary Fund for a $16.5 billion loan in October or that the IMF granted it; the alternative would have seen Ukraine staggering toward bankruptcy. But with political infighting between president Viktor Yushchenko and prime minister Yulia Tymoshenko continuing despite the crisis, with the former attempting to push out the latter and call early elections, confidence is unlikely to lift anytime soon.

With much of Europe now expected to slip into recession in 2009—growth is expected to be just 0.1% for the whole European Union—prospects for central Europe also now look far less promising. Hungary is the region’s basket case, its economic problems reinforced by profound political ones: a deeply unpopular, politically bankrupt minority government facing off against an angry rightist opposition. There was widespread relief at the unveiling of October’s $25 billion rescue package, made up of a $16.5 billion IMF standby loan and a E7.5 billion top-up from the EU and the World Bank, but the stark reality of the country’s predicament remains. With some 60% of individual debt and 30% of state debt denominated in foreign currencies—mainly euros and Swiss francs—the 27% drop in the value of the forint against these two currencies since July suggests tough times lie ahead for Hungarians individually and the national economy generally.

Some Optimism Remains

In Romania the outlook had looked pretty good. GDP, which grew around 6.3% a year between 2003 and 2007, is expected to grow by as much as 8% this year, fueled by rising living standards and a good harvest. Inflation is expected to end 2008 at around 6.5% and the current account deficit at around 15%, while unemployment will stay around 4%. The largely foreign-owned financial sector has been well regulated, and Romania’s flexible exchange rate has enabled the authorities to manage the currency rather than having to protect a fixed exchange rate, as in the Baltic states and Bulgaria.

|

Confidence in Bulgaria, meanwhile, has been severely undermined by the failure to get a grip on corruption and organized crime, which critics say reaches far into the government. The European Commission took the unprecedented step in July of freezing E500 million in aid and has warned that, due to previous misuse of EU funds, some E7 billion in structural funds could also be at risk. In the first half of 2008 Bulgaria, the poorest country in the EU, enjoyed GDP growth of 7.1%, but that will be a high-water mark. Raiffeissen has lowered its 2009 and 2010 forecasts to 3.5% and 4.5%, respectively.

The big concern is the current account deficit, which at 24.5% of GDP is by far the highest in Europe. With Sofia determined to maintain its currency board and GDP growth slowing, there are real concerns about how Bulgaria can survive without foreign support. The question is whether this will be forthcoming, given international disillusionment at the country’s shortcomings.

All is not gloom, however. The Czech Republic, having recapitalized its banks in the late 1990s, looks stable, as does Poland, which ING’s Robertson says will be the most “exciting” play for investors over 2009 and 2010. In October the hitherto rather euro-phobic Poles announced their intention to seek membership of the single currency as soon as possible, which in practice would mean 2012, although the government may hold a referendum on the issue. Given the turbulence of recent months, which has seen Iceland and Denmark both ditch their opposition to the euro, they will hardly be alone in their flight to safety.

“If this crisis has proven anything, it is that small currencies are hard to defend when international investors take fright. Membership of the euro removes a lot of the uncertainty and provides a valuable safety net,” says Robertson.

Slovakia proves the point. On January 1, 2009, this small central European country will join the single currency zone. Unlike most of its neighbors, it had a reasonably happy 2008 and expects a similar 2009. “Although it will find it hard to avoid all the knock-on effects of a slowdown in the EU, Slovakia has outperformed its neighbors and will stay ahead, thanks to the reforms carried out in the early years of the decade,” says Matteo Napolitano, Slovakia analyst at the Economist Intelligence Unit in London.

Along with other observers, Napolitano commends the current coalition government headed by Robert Fico for not following its populist instincts and broadly keeping economic policy much as it was when it took power after the elections of June 2006. Slovakia has managed to maintain high stable growth: GDP grew by 10.5% in 2007 and, despite the slowdown, is still expected to grow by 7.6% this year and some 6% in 2009, with inflation possibly slowing from its 2008 level of 5% on the back of falling energy and food prices.

So what difference will joining the euro have on this generally positive environment? The consensus is that it will make a good situation even better. “Adopting the euro will undoubtedly help Slovakia weather the turbulence better than its non-euro neighbors,” opines Eileen Zhang of Standard & Poor’s sovereign ratings team in London. She says the only thing holding S&P; back from giving Slovakia an A+ sovereign rating are doubts about the government’s commitment to fiscal prudence after eurozone entry, when, in the absence of having an active monetary policy, the country’s fiscal stance becomes all important.

The run toward the euro by non-euro EU members will be echoed by countries outside the EU rushing to join. In early November Brussels indicated that Croatia was on track to complete accession negotiations by end 2009 and could become the 28th member of the EU in 2011. Others in the queue include Montenegro—which uniquely uses the euro already—and Serbia, whose reformist government has now made early accession a priority and with whom negotiations will start once fugitive war criminal Ratko Mladic is handed over to the United Nations war crimes tribunal in The Hague. Albania, Macedonia and Bosnia & Herzegovina will also be hoping they can eventually join although, for the last two, membership looks a lot more distant.

After the turbulence of 2008, when apparent certainties proved illusory and stability has become of paramount importance, EU and euro membership have never looked so attractive.

Justin Keay