Asia’s emerging markets could not avoid the fallout from the credit crunch, but they stand a good chance of emerging stronger than ever as the dust settles.

|

The 21st century has been good to most emerging economies so far. Greater integration of supply networks and financing mechanisms have offered opportunities for the world’s lesser-developed areas to better connect into the markets of the developed world. From 2000 through 2007, emerging and developing economies as a group grew at an average annual rate of 6.4%. Emerging markets now not only share in the world’s economic prosperity but drive much of the growth.

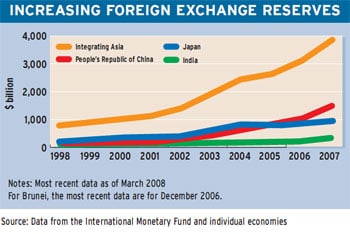

Asia’s developing markets, in particular, have performed well. The Asian financial crisis, which hit the region hard in 1997 and 1998, forced many countries to push through needed financial reforms. In the years since, Asia has cautiously allowed its economies to grow, keeping close watch on budget deficits, banking systems, financial instruments and foreign exchange reserves. As a result, Asia’s emerging markets have been enjoying relatively stable exchange rates, increasing foreign investment and strong economic growth.

The world’s emerging markets had been doing so well, in fact, that many such markets rolled through the first half of this year with only limited impact from the economic turbulence in the United States. Many felt that the strong performance demonstrated a new level of independence from the markets of the US and other developed countries. But volatility during the past few months has cast doubt on the degree of this independence.

Following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers and the rescue packages for Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac and AIG, equity markets in emerging markets tumbled. The MSCI Emerging Markets Index fell 28% in October, despite assistance for several troubled countries from the US Federal Reserve and the International Monetary Fund. Currency valuations across the developing world fluctuated, and government bond yields spiked. The turbulence showed clearly that emerging markets are still tied to the economies of the developed world.

Jonathan Anderson, emerging markets analyst for Swiss investment bank UBS, explored many of the reasons for the volatility in the emerging markets in a recent report to analysts and investors. He points out that most of these markets maintained strong economic fundamentals in the lead-up to the current crisis, but these economies faced or are facing a number of external shocks.

The first of these shocks was the subprime mortgage crisis. The crisis led many foreign investors to seek out conservative investments closer to home rather than in emerging markets. The second shock came as commodities prices dropped, largely due to slackening demand in China’s construction sector. The third shock came with the failures and bailouts of US financial firms. This triggered a phase Anderson refers to as manic deleveraging, in which investors frantically pulled out investments around the world, drying global liquidity. The fourth shock, one that Anderson believes is only in its initial stage, consists of weaker growth in the real economy as export demand in developed markets weakens.

The degree to which these four shocks influence the developing world will depend on the duration of the crisis and specific situation of each emerging economy. Domestically, most emerging markets are still in good shape, Anderson says. If the current liquidity problems persist, however, emerging markets that are highly leveraged or relatively open to foreign investment could face significant difficulties. The troubles in the US and Europe will obviously affect import demand as well, and this effect is only now beginning to show up. Once again, if the crisis persists, then export-dependent economies will certainly feel significant impact throughout their domestic economies.

While both of these factors are significant, Anderson points out that financial crises generally result from domestic fragilities, not external shocks. Most emerging markets are in much better shape financially than in the past. “The main conclusion so far,” he writes, “is that if we had to go through a global downturn and credit crisis, from the perspective of emerging markets as a whole, we couldn’t think of a better time to do it.”

Asian Economies in Strong Position

Asia’s emerging markets, in particular, are in good shape. UBS’s total risk index, which evaluates emerging market risks based on external debt, export ratio, foreign exchange coverage and other factors, did not rank any East Asian country in its top 10 riskiest emerging markets. Citi’s chief Asia economist Huang Yiping explains: “If you compare the fundamentals of most Asian economies to their state 10 years ago or to other emerging markets around the world, in terms of debt burden, financial structure, currency position and foreign exchange accumulation, most Asian economies are in a much better position.”

|

|

|

China, the region’s largest emerging market and the global driver of growth in recent years, may strengthen its neighbors’ positions as well. The country ranked lowest in risk of the 47 countries evaluated in the UBS total risk index and has ample room for policy adjustments. Over the past few years China’s central bank has raised interest and bank reserve ratios to curb lending amid fears of economic overheating. This tightening contributed to the recent cooling in commodities markets. China, if needed, can reduce these rates to stimulate the economy and increase domestic construction and, thus, commodity demand.

The Chinese government will be cautious in utilizing such policy tools, though, as some urban real estate markets in China are still showing signs of overheating, especially in the luxury-apartment segment. General housing demand remains strong nationally, though, so the government could offer policies to promote middle-class or low-income housing development. Infrastructure projects are also in line with the government’s development priorities and could further boost the construction industry and commodity suppliers.

While China’s economic health could also benefit its trading partners, Huang warns against overestimating the effect. “China’s growth will help some countries, but we have to ask, What are the things other countries are exporting to China?” he says.

Huang points out that China’s imports consist largely of components that are eventually exported as finished products. For this reason, slowing growth in the US, Europe and other export markets will have more influence over these imports than China’s domestic economy. “In relative terms, China can help some commodity exporters and some investment goods. But even for China economic growth is slowing. China will not necessarily push up growth in other regions, but it may cushion or slow deceleration in some trading partners,” Huang adds.

|

The “cushioning” effect from China, combined with the underlying fundamental strength of most emerging Asian economies, leads many to predict that, while emerging Asia is still strongly connected to the US economy, the current economic crisis will be less severe in scale and shorter in duration than in the US, Europe and Japan. The IMF does expect growth in developing Asia to slow to 8.3% in 2008 and 7.1% in 2009, down from 10% in 2007. The slowing growth shows clearly that financial circumstances in the developed world have influence in Asia’s emerging markets. At the same time, the fact that Asia’s emerging market growth will likely remain much higher than developed country growth, even in volatile conditions, does indicate that the developed world’s influence might be waning.

The crisis holds other opportunities for Asia’s emerging markets to demonstrate their growing economic status, according to Frank Song, professor of economics at the University of Hong Kong. He thinks that dropping prices in the US and Europe could provide some low-priced acquisitions for Asian companies and funds. “This is a golden opportunity for Chinese and other Asian companies as well as government and exchange reserve funds to go out on the market,” he explains. “If you believe that the markets will eventually stabilize, in the medium term, then it’s a good time.” The best possibilities for investment, Song believes, lie in areas such as natural resources, commodities and hardware, where Asian investors have ample experience.

The greatest opportunities for Asia, however, lie at home. The spread of the financial crisis in the US to the markets of Asia may provide the necessary impetus to reduce capital flows to Western markets and channel them into investments within the region. “In Asia, where you tend to see high savings ratios and less consumption, a lot of savings are shipped out to the West, with the hope that this money can be used more efficiently in the West,” says Song. “But we found out that it is not used more efficiently; it was just a bubble. So this type of relationship cannot be sustained anymore.”

Regional Cooperation Is Key

To better utilize the region’s savings, Asian countries will need greater coordination on macroeconomic policy and increased cooperation to build the financial structures and organizations necessary to ensure efficient capital flow. The eastward spread of US economic turbulence could speed up this effort toward greater regional cooperation.

“Asia must make growth more sustainable and use savings more efficiently,” asserts Song. “We must structure the financial system in an efficient way so we can mobilize savings domestically to stimulate consumption, stimulate investment and have a more domestically driven economy. It is a big challenge.”

|

|

|

The Asian Development Bank in May published “Emerging Asian Regionalism,” offering some ideas on how to meet that challenge. Despite growing economic integration, the report observes, macroeconomic policy coordination among the countries in Asia remains limited. Such coordination must improve, the report’s authors stress, to address global trade imbalances. The report recommends a number of policy initiatives, including more monetary and financial policy cooperation, increased regional market supervision and regulation, greater short-term financing options, better labor migration rules and more coordinated sustainable development strategies.

“A challenging period may lie ahead,” the report reads. “Global imbalances that appear increasingly unsustainable must be resolved. This will require major adjustments around the world; in Asia, it will mean reorienting output from exports outside the region to consumption and investment within it. And these shifts may need to occur rapidly if, for example, the current credit market turmoil and global slowdown deepen.”

During the months since the ADB report was published, the “credit market turmoil” has indeed deepened drastically, and the need to make the shift toward greater coordination and stronger regional financial mechanisms has intensified. The emerging markets of Asia grew rapidly over the past 10 years. The next great challenge will be for them to grow together.

Thomas Clouse