Investors Brace Themselves For A Bumpy Ride

Russia may have been promoted to investment grade, but its political and economic turbulence show no signs of abating.

Until relatively recently, it looked like Russia was going to get a lot less exciting. Russian President Vladimir Putin seemed to be bringing an end to the stomach-churning political instability of the Boris Yeltsin presidency, through strengthening the grip of the Kremlin on the levers of power. A comprehensive reform program appeared poised to destroy the lingering remnants of the command economy. Meanwhile, strong commodities prices cooperated, ensuring that the economy grew like a snowdrift in Siberia, and thereby keeping the reform window open.

Not so fast, though. The changes in Russia since the dawn of the new century, when Putin assumed power, have been dramatic and far-reaching. The disarray that characterized Russia in the 1990s is a distant nightmare. But a range of fresh challenges facing the Kremlin and the Russian economy means that a lot of the assumptions about the new Russia are looking out of date. If anything, Russia in 2005 will be more interesting than ever.

|

Politics Plays Star Role |

|

In Russia, politics still plays a central role in defining the direction of the economy and the investment environment. And the relative political stability and predictability that Putin has brought to Russia are among his key achievements in the eyes of most investors. So cracks in the Putin faade of political invincibility are a cause for genuine concern. Since taking up residence in the Kremlin, one of Putins key aims has been to reverse the creeping federalism that eroded the power of the Kremlin during the Boris Yeltsin era. Early on, the former KGB colonelwho never pretended to be a devoted disciple of democracymoved quickly to centralize power by re-molding the bureaucracy to be directly accountable to the president, establishing iron-clad control over both houses of parliament and reducing distracting public debate through the closure of independent media outlets. Critically, close to all tax revenues now are submitted to the federal, rather than regional, coffers. In 2004, taking opportunistic advantage of a rash of terrorist incidents, the Kremlin announced a number of political reforms focused on reigning in regional sovereignty and increasing stability, which Peter Zeihan of Internet intelligence company Stratfor.com called a personal coup by the president against the institutions of the Russian state. Most notable were the elimination of single-mandate seats in the State Duma, the lower house of parliament, and the termination of the popular election of governors. Implementation of Putins vertical power agenda will be a centerpiece of the Kremlins political program in 2005. Many analysts are wary that centralization will have an adverse effect on Russian competitiveness. Strengthening of the bureaucracy eventually leadssimilar to Soviet timesto the incapacitation of the central government and the weakening both of the regime and of the state, warns Alexander Bim, a senior analyst with IMAGE-Contact Consulting Group in Moscow. Theres also the danger that centralizing power is itself becoming an end, rather than a means to push through unpalatable but necessary reforms. The consolidation of political powerpreviously justified by some policymakers and observers as a means to facilitate rapid modernizationis starting to take on a life of its own, observes Alexander Kim, a strategist at Moscow brokerage house Renaissance Capital. |

Presidents Popularity Wanes

On another front, Putin has said he will not support attempts to change the constitution to allow him to run again in 2008. It will be important to watch for measures his camp takes to remain in power upon the end of his second term, without resorting to blatantly extra-constitutional measures. One theory making the rounds is that Putin will try to bring about the election of a puppet president in 2008, who would be willing to step aside when Putin becomes eligible for another two-term stint in 2012, thereby remaining within the letter of the law of the constitution.

Until recently, Putins sky-high approval ratings virtually guaranteed that the Russian electorate would feed what Alexei Moisseev of Renaissance Capital calls the presidents Napoleon complex. But Putins standing has recently eroded dramatically: The Levada Analytical Center, a respected independent pollster, reported that the presidents trust rating fell from 58% in 2003 to 39% in late 2004. Even the Public Opinion Foundation, a pro-Kremlin polling organization, says that the percentage of respondents who said they would vote for Putin in an election fell, to 42% in January 2005 from 65% in January 2004.

One cause of the decline has been the recent mishandling of the implementation of a series of long-anticipated social reforms that would monetize social payments to the countrys 40 million pensioners. When cash payments in lieu of free transportation, subsidized health care and utilities, and other long-standing benefits turned out to be far less than necessary to compensate for the trimmed benefits, the pensioners who previously had been some of Putins strongest supporters took to the streets in January. The Kremlin backpedaled furiously, reinstating some benefits and browbeating regions where payments werent made as scheduled.

Putin may use the fiasco as one pretext to reshuffle his cabinet, likely jettisoning Prime Minister Mikhail Fradkov, who has failed in managing both the government and the economy. Economic development and trade minister German Gref and finance minister Alexei Kudrin, the remaining liberal reformers in the cabinet who have appeared increasingly under siege, may also be shown the door, although both have survived years of premature political obituaries.

|

Reform Program Falters |

|

Putin has engineered significant land, tax, administrative, pension, judicial, corporate governance and labor reforms. And in trying to reform public tariffs, Putin is showing courage at the expense of his personal popularity, argues Peter Lavelle, an independent political analyst based in Moscow, and sending the message that reform is still solidly on the agenda. But implementation of reform has been uneven at best and has fallen short of what is required to lay the foundation for a genuinely liberal market order. And regardless of who is tapped to head up the government, the progress of the Putin reform program is likely to be only sporadic and limited, says Bim, and characterized by general stagnation.

The court system, despite improvements, is still monumentally inefficient. Corruption remains rampant, as reflected in the sharp deterioration of Russias relative ranking in corruption watchdog Transparency Internationals Corruption Perceptions Index, from 71 in 2002 to 90 in 2004. The so-called Yukos affair, which ended with the sale of the key asset of what was Russias largest oil company, demonstrated how state might trumps investor rightsas well as the legal process. Meanwhile, natural monopoly reform, which was to address the remaining vestiges of the command economy by opening the electricity, gas and banking industries to market forces, is barely limping along. The power industry is being reformed without being restructured, says Caius Rapanu of UralSib investment bank in Moscow, which is a recipe for future distortions in the economy. New companies formed in the industry will be made to compete against each other, although Unified Energy Systems [Russias national monopoly power provider and distributor] will still own them all, he observes. Gas giant Gazprom is moving in the opposite direction of market reform and toward becoming a hypermonopoly, in the words of Gref. The anticipated merger of government-owned oil producer Rosneft with Gazprom and the gas companys acquisition of Yuganskneftegas, the main production asset of Yukos, would make Gazprom a big player in the oil marketin addition to controlling by far the worlds largest reserves of natural gas. The company continues to subsidize the Russian economy, selling gas to Russian consumers at a fraction of international prices. A long-anticipated share structure liberalization, slated to take place in the first half of 2005, would position Gazprom to be one of the biggest and most liquid equities in the emerging market world. Not everyone is excited at the prospect. I own Gazprom shares because I have to, says one London-based asset manager who asked not to be named, but I have to hold my nose, because its one of murkiest, least transparent companies in Russiaor anywhere, for that matter. The dichotomy between increasing political centralization and the floundering efforts to open up the economic arena underscores what Rapanu at UralSib describes as an underlying schizophrenia of the Putin program. Can Putin centralize the political environment while liberalizing the economic arena? he asks. Others question whether perceptions of Putins power are overstated. His solemn promises to not run Yukos into the ground, for example, were spectacularly broken within months. [Putin] has to virtually put a gun to the head of each of the largely useless 1.2 million state bureaucrats to get anything done. It is a myth that the Kremlin has its eyes everywhere and is controlling everything, says Lavelle. |

Imbalances Threaten Economy

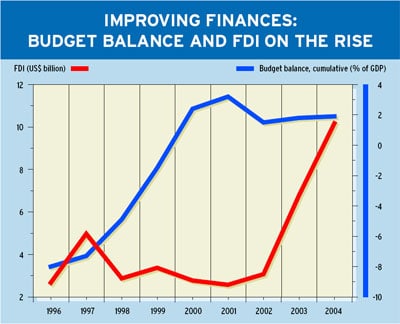

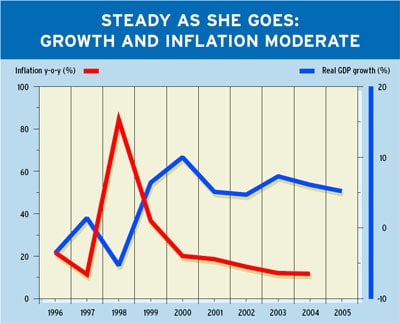

Arguably, the Russian economy is doing just fine without more reform. In late January, Standard & Poors became the last of the three rating agencies to upgrade the country to investment grade, reflecting improvements in debt levels and external liquidity. The country enjoys an enviable fiscal situation. GDP has grown 35% since 1999 and is set to jump another 5% to 7% in 2005. Foreign reserves are up more than eight-fold over the same time period. The ruble has stabilized. Personal income has been growing rapidly, and average real wages are up around 60% over the past 10 years. In early February the country repaid its remaining debt to the International Monetary Fund, ahead of schedule. Russia will probably join the World Trade Organization early in 2006, says Yaroslav Lissovolik, an economist at Moscow brokerage house United Financial Group. Even though, as he says, the effect will be largely sectoral and for the most part confined to the steel sector, Russia joining the global free trade club will be a powerful symbol of its progress since the end of communism.

But clouds are forming. The strong commodities prices that have played a central role in driving Russias economy may have a more insidious effect. High oil prices may well allow the subsidization of poor policy for some time, but unless there is a change in direction, it is a matter of when, not if, growth turns to stagnation, says Roland Nash, chief strategist at Renaissance Capital. Non-oil economic growth slowed for the sixth consecutive month in December, to 3.9%, and in November the Moscow Narodny Bank manufacturing index showed negative growth for the first time since 1998. Inflation remains stubbornly high as the government has repeatedly failed to reach its inflation targets. Continued real appreciation of the ruble is leading to the further deterioration of competitiveness.

Meanwhile FDI remains pathetically low and fell sharply in the second and third quarters of 2004. After briefly reversing, capital flight resumed in 2004, suggesting that domestic investors are finding more attractiveand safercountries to park their cash. The market for initial and secondary public offerings has been strong, which on the one hand underscores the increasing depth of the countrys capital marketsbut insiders selling out is rarely a good sign, either. Particularly concerning was the December 17 sale by Deutsche Telekom of most of its stake in Mobile TeleSystems, Russias largest cellular phone company. This sale is likely the beginning of a rush of foreign investment out of Russia, says Zeihan of Stratfor.com.

The similarities with the environment that existed before the August 1998 financial crisis are haunting for some investors. Its difficult to call a top, but you have to wonder when you see all the Russian money flowing out, says one Moscow-based fund manager.

Russias was one of the worlds worst-performing equity markets in 2004, due in part to the Yukos affair. Investors who have been spooked by Russias anti-oligarchic efforts have not seen anything yet, says Zeihan.

|

Risks Unnerve Investors |

|

Until perceived levels of risk decline, investors may remain skittish. Attempting to price the risk that a bunch of bureaucrats feel empowered enough to clobber some dodgy Russian billionaire is beyond the job description of most fund managers. Better to focus scarce resources on less volatile countries, says Nash of Renaissance Capital. Finally, prospects for Russia on the geopolitical front are looking dim as well. One of the biggest losers in the battle for the presidency of Ukraine was Putin, who had personally lobbied hard for Viktor Yanukovych, the defeated protg of incumbent Leonid Kuchma. When opposition candidate Viktor Yuschenko took the oath of office, following widespread protests resulting in a re-run of the elections, Ukraine in effect escaped the Russian gravitational pull. The disastrous war in Chechnya drags on, as another symbol of the decline of Russian might. But dont write Russia off. With the scramble for energy resources rising to the top of the global geopolitical agenda, Russia is in prime position, as the worlds second-largest exporter of oil and with the largest natural gas reserves. And while he comes under pressure from a range of sources, dont expect Putin to follow anyones path but his own, in any sphere. Under Gorbachev and Yeltsin, Russia danced like a caged bear for vodka shots for the West. Putin prefers beer and doesnt dance for anyone, remarks Lavelle. Investors will have to work hard to stay in step. |

Kim Iskyan