India recently overtook China as Asias fastest-growing economy. Its showing no signs of slowing down.

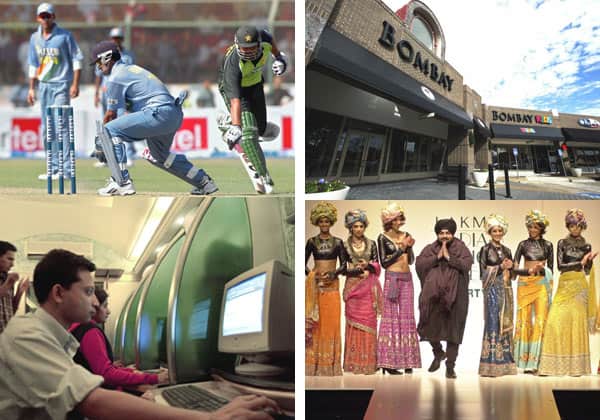

India has long been a land of stark contrasts, and its recent economic growth has only added to them. Although constrained by poverty and third-world infrastructure, India has a rapidly growing economy and is a world leader in software and IT development and a major manufacturing hub for leading carmakers such as Hyundai and General Motors.

People still think of India as a backward country, not recognizing how it has caught up in terms of technology and to a lesser extent infrastructure, says Dr Sivaprakasam Sivakumar, an investor in India since 1997 and managing director of Boston-based investment banking firm Argonaut Capital. It takes time for people to understand the paradox that is India.

That paradox has its beginnings in the foreign exchange liquidity crisis of 1991, which forced the government to initiate a series of economic reforms that led to higher and more robust rates of economic growth. The Central Statistical Organization predicts that overall GDP growth will reach 8.1% for the financial year 2003-2004. In the third quarter India overtook neighboring China as Asias fastest-growing economy, with double-digit growth of 10.4%, which economists attribute to a rebound in the agricultural sector brought on by last years favorable monsoons, following severe drought in 2002.

The agricultural sector accounts for almost a quarter of Indias GDP and employs approximately 70% of the population.

But Indias emergence is not just an agrarian success story. Growth is much broader based, reflecting a wide range of both structural changes and cyclical trends, notes Helen Henton, senior international economist for Standard Chartered Bank. The monsoon will continue to cause volatility in growth, Henton says, but the opening up of other industries following reforms in the 1990s meant that, even during the drought, growth still remained at 4%.

That would not have happened 20 years ago, she says.

Government estimates predict exports will grow 12% per annum, boosting export earnings from $44.56 billion in 2000-2001 to $80 billion by 2006-2007 and raising Indias share of world exports from 0.7% to 1%. A significant chunk of that growth is expected to come from internationally competitive industries such as the auto parts and pharmaceuticals sectors. Longer term, pharmaceuticals exports may be significantly larger than IT services exports, says Sivakumar. It currently contributes $2.5 billion, less than 1% of GDP, but according to Sivakumar Indian companies such as Ranbaxy are generating more than $1 billion in revenues, most of which comes from exports.

Indias software and IT sector certainly put India Inc. on the map. The Indian software services sector has grown at an average annual rate of 41% since 1997, its overall contribution reaching $9.6 billion by 2002-2003, constituting 12% of total exports, according to Standard Chartered Bank. Henton believes that growth rates of 35% to 40% in the business processing outsourcing (BPO) sector are unsustainable in the long term but that robust levels of growth would continue as outsourcing of services was still a relatively new concept.

S. Gopalakrishnan, co-founder and chief operating officer of leading Indian software firm Infosys, acknowledges that the boom period of the late 1990s, which saw the Indian IT sector awarded contracts on the back of the rise of the Internet, will not be repeated. India is also facing competition from alternative low-cost centers in Asia and Eastern Europe, which Henton views as a greater threat in the medium term to Indias flourishing BPO sector. India cannot afford to just focus on costs; they need to move up the value chain, she says.

The success of the IT sector is also having a knock-on effect on other industries. Two years ago Indian companies thought they couldnt compete on a global basis, observes Girish Paranjipe, president, financial solutions, for Indian IT company Wipro. Today Indian companies can stand on their own two feet and compete globally.

Indias car industry is flourishing, with improvements in quality standards aided by investment in technology and automation. Sales of cars and two wheelers from India grew by more than 65% in 2002-2003, and Indian companies such as Bharat Forge won major outsourcing contracts for the manufacture of car components from Ford Motor and Daimler Chrysler.

We are seeing the benefits of computerization in the manufacturing and services sector, says Gopalakrishnan. The challenge now is extending that to a broader base, including agriculture, which is still dependent on the monsoons. We have focused so much on exporting IT, instead of using IT domestically, says Romesh Sobti, executive vice president of ABN AMRO Bank in India. There are pockets where that is already happening, such as the automobile industry, but it hasnt reached the middle market yet.

In an effort to address some of Indias glaring infrastructure constraints, the government has opened up the power, roads and telecom sectors to private investment. On the railways now ticketing is computerized, and the government is allowing tax returns to be filed electronically, Gopalakrishnan notes. The poor state of the countrys infrastructure has long tempered foreign investors enthusiasm for India, and improvements will be vital for sustaining higher rates of growth.

|

|

|

Ambitious Growth Targets

The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce & Industry (FICCI) has an ambitious framework for achieving an annual growth rate of 10% and creating 60 million jobs. We think in one or two years this is conceivable, says FICCIs secretary general Amit Mitra. The bulk of this growth will come from what Mitra terms the second green revolution, led by the creation of industries such as agro-processing, which he says will have a knock-on effect further downstream.

Yet Henton maintains that given Indias large fiscal deficit, which currently stands at 10% of GDP, an annual growth rate of 7% is more realistic. India also needs to improve tax collections, particularly in agriculture, which isnt taxed at all, she continues. However, she is heartened by the consensus for reform in India, which she does not see decelerating despite the bureaucratic hurdles that exist in a country made up of 25 states. Bureaucracy in general led to procedural delays, which 96% of foreign investors rated as quite to very serious in FICCIs 2003 survey. A further 71% said India still had some way to go before Made In India was synonymous with quality.

The Indian authorities have laid the groundwork for further reforms, but, as Sivakumar points out, India has its own way of moving forward, which entails taking two steps forward and one step back. And with the 1997Asian meltdown still fresh in peoples minds, India is reluctant to relax controls on foreign investment too quickly. Radical reforms will only create a huge backlash, says Sobti. A step by step approach has worked well for the country.

Anita Hawser