A multi-billion-dollar industry faces evolution, not revolution, after 18 months of turmoil.

For a whilejust a whileback then, it looked like the game was over for the worlds accounting giants. When Enrons late-2001 death spin sucked in accounting firm Andersen, the industrys Big FiveAndersen along with PricewaterhouseCoopers, Ernst & Young, KPMG and Deloitte Touche Tohmatsusuddenly shrank to the Big Four.

Worse, the worldwide reaction to the revelation that an Andersen partner had aided and abetted the Houstons energy giants financial card tricksand that it probably wasnt an isolated incidentthreatened to shred the all-singing, all-dancing business model that had propelled the full-service accounting firms to multi-billion-dollar revenue gushers.

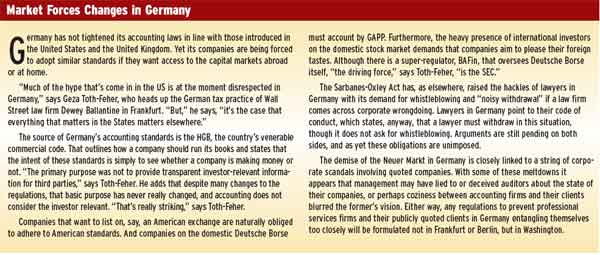

While mooted changes reflected the wrinkles of business laws in countries like Germany,Japan or the United States, at the heart of most reforms was the desire to separate the audit function and other ancillary businesses. Taken to its logical conclusion, that threatened the break-up of the integrated accounting firm.

That was then, this is now. In late January the SEC announced guidelines for auditing under the Sarbanes- Oxley Act of July 2002.Those rules imposed curbs on nonaudit work that an accounting firm doing audits can perform for its clients. In the same month the UK Trade and Industry secretary Patricia Hewitt recommended, after a yearlong inquiry, that a new industry watchdog should review conflicts of interest between auditors and their clients.

In these key jurisdictions, at least, accounting firms have had some shackles placed upon the amount of work they can do for one client. Firms will have to tread more warily and demonstrate the integrity of their auditing for all to see. But the changes dont look to be so stringent that they would force a break-up of the firms themselves.

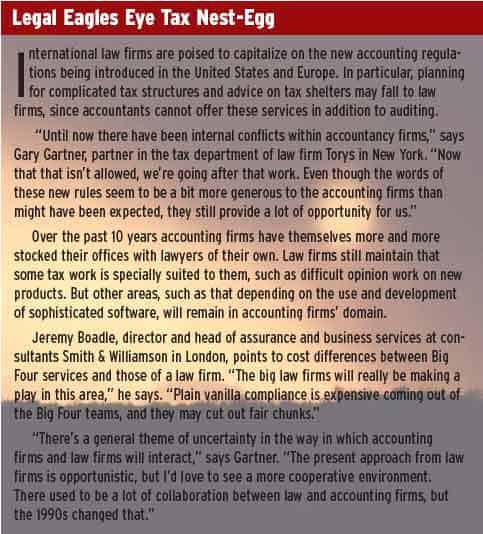

What we see is that the world wants independent auditing, says Don Murray, the CEO of Resources Connection, a California-based consultancy firm that offers auditing services. The Big Four are doing a lot of lobbying, and they believe theyve survived.They dont want to give up nonaudit work, and they dont want to be independent. Crucially, the SEC allowed accounting firms to continue supplying lucrative tax planning work to audit clients.

Mandatory rotation of auditing firms every five years was at one time on the agenda in the United Kingdom; instead the government recommended replacing audit partners within firmsa provision that is far easier for accountancy firms to live with.

Industry watchers say much will now depend on how companies themselves respond to the new guidelines in key jurisdictions. Some companies may choose to shift consulting work to firms with which they have no audit relationship; others may choose to be more open in their annual reports.What seems clear, however, is that changes in the industry landscape are likely to be at the margin rather than tectonic in nature.

And while the Big Four maintain a stranglehold on the accounting industry, smaller players can only chisel away at the edges.

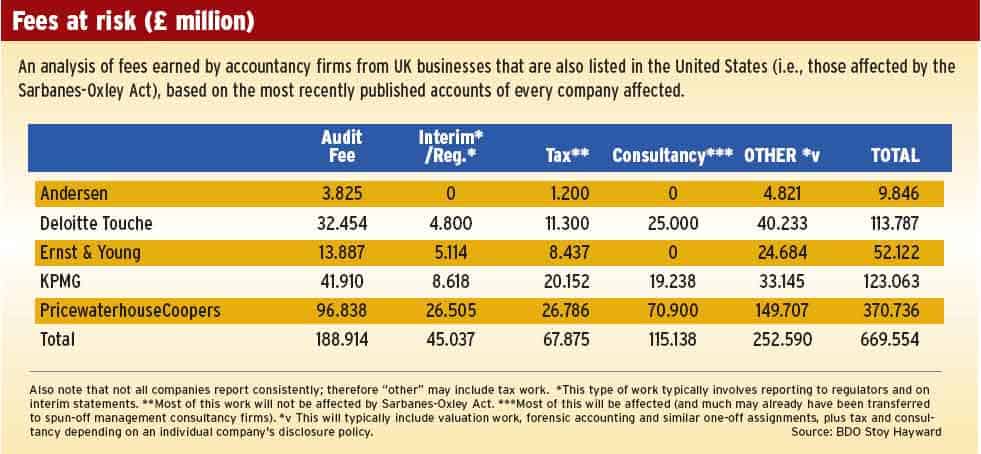

Key to the SEC guidelines is protecting the principle that auditors must not audit their own work.These rules are in part replicated in the UK, where at the same time the government laid out a new regulatory framework for accounting firms and announced a review of possible conflicts of interest raised by auditors offering non-audit work. Regulators will demand greater disclosure of the relationship between companies and their auditors and fuller detail of fees paid for audit and non-audit services.

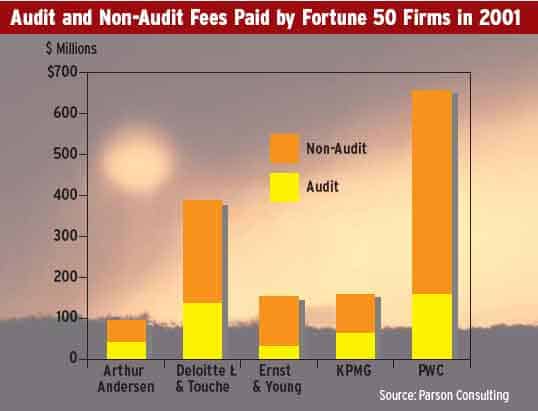

The cost of giving up non-audit tax work is high. For instance, in the year ended June 2002, PricewaterhouseCoopers notched up more than $4 billion, 30% of its global income, through tax and legal services. KPMG and Ernst & Young earn more than 35% of fee income from tax work, according to UK accounting information provider Lafferty.

The SECs new rules list nine non-audit services that it judges impair a firms independence and are hence banned.They include bookkeeping, actuarial work, design and implementation of financial information systems and provision of legal services. Some tax services are allowed, however, so long as they are approved by an audit committee. The initially proposed rules that the SEC put out for comment had carried the possibility that all tax work might be considered to raise conflict issues.

At the end of the day, in terms of the final rules I think its fair to say that the SEC has confirmed that the tax practice we have is not in conflict with auditor independence, says Richard Kilgust, global public policy leader at PricewaterhouseCoopers in London. He points out, for example, that PwC does not represent clients in front of tax courts, district courts or federal courts of claims activities that are proscribed.

But Gervase MacGregor, a London-based partner in the fifth-largest international accountancy firm, BDO Stoy Hayward,says that the Big Four have been losing out on tax opportunities for some while:I have seen large companies increasingly prepared to look outside the global firms, because often conflicts of interest in litigation take out half of the Big Four from consideration, he says. In forensic investigations we have seen an increasing number of invitations for tender for projects with large PLCs that a year ago would have automatically gone to the auditor. Under Sarbanes-Oxley, this will happen more and more, he adds.

Much of the new regulatory regime is dependent on interpretation by audit committees, and while SEC rules may allow auditing companies to provide some non-audit tax work,the question is whether audit committees will be comfortable approving this.I think youll find all kind of different reactions within the marketplace, says Kilgust. There will be some companies certainly that are going to make their own decisions as appropriate for them.

Smaller accounting firms are hoping,and confident,that this will go in their favor.Especially where tax advice may be racy or innovative, people will always be skeptical,and companies will want independenceand for independence to be seen, says Kevin Perry, the CEO of Parson Consulting, a Chicago-based financial consultancy. I believe a lot of non-executive boards will take a stricter view compared to minimum standards.

Perry says that,in the same way,companies in the United Kingdom will effectively regulate themselves more stringently than the letter of the new rules may demand.In the UK,whats allowed and not is much more a question of discretion,he says, but in reality companies will uphold tougher standards just to be more credible. Some companies had, before the fleshing out of Sarbanes-Oxley, opted only to allow their auditing accounting firms audit work. In the case of the Walt Disney Company, this move came as a direct result of shareholder pressure.The California media conglomerate decided, before the spinning off of PricewaterhouseCoopers management consultancy arm, to use the firm only for auditing.Apple Computer was another large company to move early to segregate accounting firms, though the company retained auditors KPMG for basic nonauditing work like tax compliance.

Richard Kilgust says that in the past companies may have been acting to pre-empt changes that could be expected under the new SEC regulations. Now that the regulator has shown its hand, better decisions are possible:Companies were stepping into a void of knowledge in terms of what was appropriate and were making their own decisions, he says.Now with these new rules theres a [good] deal of clarity that weve needed for the last 12 months.

Inevitably, much work thats taken away from one Big Four firm will simply be given to another. But there are other reasons, the smaller firms say, why more work will drip down to others.Number one,theres more of it about and it pays more.While accounting scandals may have tarnished the industry, they have sent board members rushing for advice ever more readily.There is already clear evidence of increases in audit feesby up to as much as 25%.

Kevin Perry says that one issue ripe for debate in the accounting industry is that of cross-board conflicts of interest. I might be the CEO of a company and a non-executive elsewhere. Maybe the one company uses x for auditing, but then there can be a conflict of interest making decisions at the other. Ninety nine percent of the time this would be totally honest. But this is something people are starting to talk about.

Might large firms be forced to split their businesses in the way they did earlier with their consulting firms? Independence between auditing and non-auditing services stretches a firms ability to gain the latter since auditing a company gives a thorough knowledge of what that company needs.An SEC regulation stating that tax planning should be treated skeptically by an audit committee if it was brought to the company by the auditor blunts this advantage.And providing more non-audit work for non-audit clients means accepting lower profit margins than combining audit and tax work.

If regulatory pressures increase and competition from niche professional services providers rises, some people in the industry think that big players will devolve. Structures arent as cohesive as people might think,says David Hunt,director in assurance and business services at consultants Smith & Williamson in London. He says that if the Big Four broke up, the process would be triggered by a group first unwinding in one country and then creating a domino effect.But, he says,it would take an awful lot to make a firm in one country change horses like that.And I think that it will anyway be at least two to three years before we see the results of whats happening now.

In the meantime, second-tier and specialized accounting firms,as well as law firms,may continue to chip away at the leaders workload. Their job is made easier by ongoing changes in corporate governance rules, but it is still a Herculean task. The Big Four still provide the brand name, says one partner at a small firm,and they still provide the ability for an accounting committee to say afterwards, Well, we went to the biggest and the best.

Benjamin Beasley-Murray

covers finance for Global Finance.

Email: editorial@gfmag.com