ANALYSIS

FINANCIAL CENTERS

Established financial centers are seeing their dominance challenged in the aftermath of the credit crunch.

BY ANITA HAWSER

In early April, as leaders from the Group of 20 countries gathered with the expectation that they would usher in a new world of global financial regulation, it seemed fitting that the location for the historic summit was London. After all, when it comes to foreign exchange, bonds and derivatives markets, London is a leading global financial center, and it seemed only natural that it should lead the world out of the current crisis. Arguably, London also has a lot more to lose than other financial centers when it comes to the redrawing of the global financial regulatory landscape, so the city has a vested interest in appearing to lead the world back from the brink of disaster.

In early April, as leaders from the Group of 20 countries gathered with the expectation that they would usher in a new world of global financial regulation, it seemed fitting that the location for the historic summit was London. After all, when it comes to foreign exchange, bonds and derivatives markets, London is a leading global financial center, and it seemed only natural that it should lead the world out of the current crisis. Arguably, London also has a lot more to lose than other financial centers when it comes to the redrawing of the global financial regulatory landscape, so the city has a vested interest in appearing to lead the world back from the brink of disaster.

The scale of the shrinkage is largely dependent on how hard governments and regulators in the G-20 countries come down on the financial services sector. So far, all indicators suggest that they are unlikely to get off lightly. “A bad reaction, particularly for London, would be to become defensive and try to protect jobs,” says Mainelli, pointing out that London became Europe’s leading financial center in part because of the flexibility of its labor laws. An equally bad reaction, Mainelli continues, would be to assume that lack of regulation was the cause of the credit crunch; in fact the opposite might be the case. “There is a good argument that overregulation was the cause, leading to restrictive markets with the result that there were four global auditing practices, two credit rating agencies, two actuarial firms and fewer than two-score global investment banks,” he says.

The scale of the shrinkage is largely dependent on how hard governments and regulators in the G-20 countries come down on the financial services sector. So far, all indicators suggest that they are unlikely to get off lightly. “A bad reaction, particularly for London, would be to become defensive and try to protect jobs,” says Mainelli, pointing out that London became Europe’s leading financial center in part because of the flexibility of its labor laws. An equally bad reaction, Mainelli continues, would be to assume that lack of regulation was the cause of the credit crunch; in fact the opposite might be the case. “There is a good argument that overregulation was the cause, leading to restrictive markets with the result that there were four global auditing practices, two credit rating agencies, two actuarial firms and fewer than two-score global investment banks,” he says.

Mark Weil, head of EMEA financial services at consultancy Oliver Wyman, says that if the UK joins other major economies in agreeing on a very restrictive set of rules, then firms are likely to relocate elsewhere. This would be more harmful for London, as historically the benefit that the UK has enjoyed over the US is that its principles-based regulatory approach has been “broadly business friendly,” says Weil.

Ultimately, heightened regulation could level the playing field between New York and London. “New York became a major financial center because it has a large domestic financial market to support,” explains Tholstrup. “The same is not true for the UK, and it is going to be more difficult to sustain in a tougher regulatory environment where financial innovation is not going to be as popular.”

International harmonization of regulations will also make it more difficult for financial institutions to arbitrage between financial centers, says Tholstrup. In the past, financial service providers have been able to escape the heavy hand of regulation by locating certain parts of their businesses offshore. However, US and European governments are working to tighten the rules on offshore “tax havens,” to strip them of their non-disclosure or secretive status.

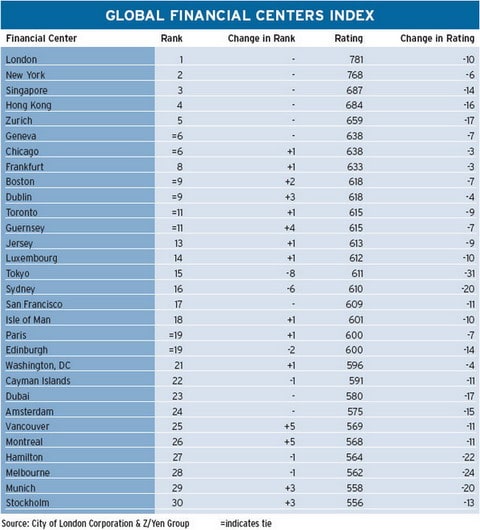

So will the concept of the global financial center disappear altogether? Dan Alamariu, an analyst with Washington-based political risk adviser Eurasia Group, says what is more likely to happen is that financial centers will become more dispersed. But, he adds, that does not necessarily mean that Hong Kong, Singapore or Dubai, which are steadily gaining in importance, will steal New York and London’s thunder. “These other centers may play a bigger role in Asian financial markets. However, in London and New York the structural aspects—talent pool, political stability, business savvy—are already there,” he says.

Some believe China’s role will grow. According to Z/Yen, China’s development as a third global financial center hinges on whether China establishes a regulatory regime that attracts or repels international business. If it repels business, Z/Yen says it could create “offshore pools of Chinese money” for another Asian center. A major factor that remains in New York and London’s favor is their well-established legal and political framework, something that China lacks, says Weil.

If a new global financial center is to emerge, it is unlikely to happen rapidly, says Alamariu. “You can raise capital in Dubai and Shanghai, but the ability to have capital markets depends on a number of structural factors —a deep and well-educated workforce, political and legal stability—and some of these things don’t exist in places like Dubai or Shanghai.” Alamariu says there is still the incentive to list in the UK and US because they have more-stable regulations and capital markets.