FOREIGN EXCHANGE

The apparent cause of the turmoil in global equity markets and emerging market currencies that began in late February was Chinas crackdown on unauthorized stock trading, which triggered an 8.8% decline in the Shanghai stock market in a single day.

One could imagine that this is precisely what the authorities wanted to happen, says Carl Weinberg, chief economist at Valhalla, New York-based High Frequency Economics. Before the selloff Shanghai shares were up more than 130% in the preceding 52 weeks.

China is not crumbling, Weinberg says. The selloff reflected market reaction to new public policies aimed at pricking a bubble before it gets too big. Business in China will be good for foreign companies for decades to come, he adds.

China is taking out all of its weapons to club the economy and the stock market, says Dennis Gartman, editor and publisher of the Gartman Letter, a Virginia-based market analysis and forecasting service. In mid-February the Peoples Bank of China announced that it was raising its bank reserve requirements by 50 basis points, the fifth increase since June of last year.

Reserve requirement increases are a central banks heavy cudgel with which to get the interest of the market, Gartman says. They are bludgeons to the forehead, he adds. As they said in times past, when you wanted to get a mules attention, a well-placed two-by-four to the forehead would do it. The central bank is doing this to the mule that is the Chinese economy and stock market, he says.

The Peoples Bank of China said that going forward it intends to use a comprehensive set of monetary policy tools to soak up excessive liquidity in the banking system.

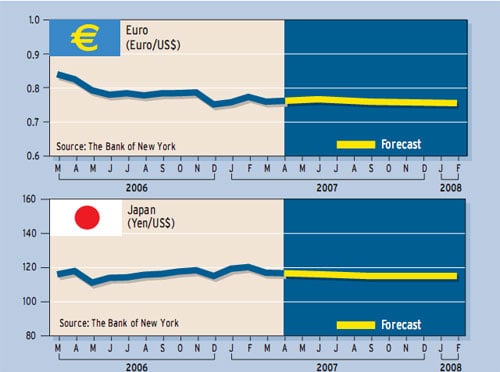

Meanwhile, the Japanese yen began rising sharply relative to the dollar, the British pound, the euro and most other currencies in mid-February. An improving Japanese economy and rising interest rates contributed to the yens advance, which triggered an unwinding of the yen carry trade, whereby investors have been borrowing cheap yen and investing in higher-yielding securities in the United States, New Zealand and elsewhere.

Investors who have borrowed yen, including hedge funds and major institutions, have found themselves in the increasingly uncomfortable position where the profits earned on their yen borrowings were being lost swiftly as the yen increased in strength, Gartman says. They faced the prospect of having to pay back their loans with an increasingly expensive currency.

Weve seen this before, Gartman says. In the summer of 1998 the carry trade ended violently and in obvious tears. We hope it wont end quite so violently this time, for we remember the seriousness of the events of the late summer of 1998, and we wish not to revisit them, he says.

We fear that the unwinding of the yen carry trade shall be protracted, shall be eventful and shall not be pretty, Gartman says. Such is the nature of these things, for although the characters of these stories change over time, the plot lines remain eerily the same. The building of these positions took years, he says, and their liquidation will require weeks, if not months, to effect.

While US markets initially showed little reaction to comments by former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan suggesting that the US economy could slip into recession later this year, the reaction in Asia was more severe. There is a saying in the export-dependent region that when the US catches cold, Asia gets pneumonia. Greenspan later clarified his remarks to indicate that while a US recession is possible, it is not probable. He also reiterated that the worst is over for the US housing market.

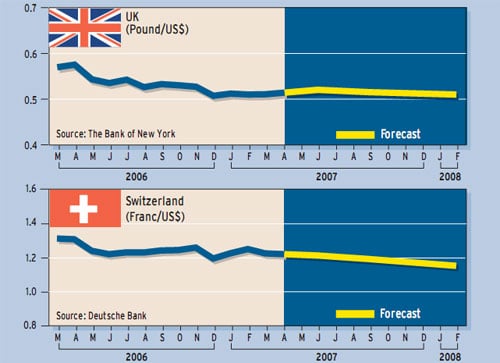

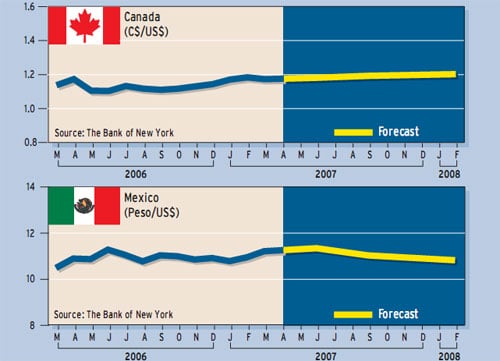

The dollar fell to a two-month low in late February. Along with worries about the unwinding of the yen carry trade, sentiment toward the dollar soured on fears of the potential knock-on impact from the woes of sub-prime mortgage lenders, anxiety about the confrontation with Iran and expectations of soft US economic data, says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman in New York.

The fact that the business cycle is increasingly mature in many countries naturally raises the risk of a setback, Chandler says. However, one reason we think that markets can navigate the period ahead is that, from an economic viewpoint, the consumer is keeping the global expansion on track, he says.

The US job market has remained robust, Chandler notes, with job growth averaging 180,000 per month over the past year. Eurozone employment has firmed, and job growth in Japan has returned to positive territory, he adds.

US personal income rose 1% month-over-month in January and was up 5.3% from a year earlier. Personal spending rose 0.5% in January, for a gain of 5.5% year-over-year.

The personal income and spending report dovetails nicely with recent reports reflecting the ongoing strength of the US consumer in the new year, says Michael Woolfolk, senior currency strategist at The Bank of New York. This is important given that housing continues to show notable weakness, he says. Greenspans warning of recession might not be off base, he says, were problems in sub-prime borrowing to become more widespread.

US manufacturing showed surprising strength in February, with the ISM manufacturing index rising to 52.3, a three-point gain from January. Renewed growth in manufacturing employment is an unexpectedly pleasant surprise, Woolfolk says. If this continues, it may provide some much needed support to the economy as the US housing market takes its next leg lower.

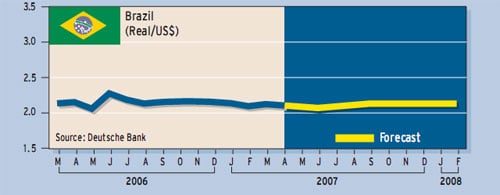

While credit spreads of emerging market bonds to US treasury securities widened in the aftermath of the equity market turmoil last month, emerging market currencies proved fairly resilient. The high-yielding Brazilian real, for example, held up comparatively well. Despite the heightened volatility in the market, the Brazilian central bank still bought dollars in the market, although it was certainly not aggressively paying up for dollars, says Clyde Wardle, emerging market currency strategist at HSBC Bank in New York.

Brazils foreign currency reserves have now hit the $100 billion mark, and finance minister Guido Mantega says the high level of reserves acts as a vaccine for the country against international financial turbulence. The reserve cushion lowers Brazils borrowing costs and reassures investors that the government is able to pay back its debts.

Gordon Platt