Businesses, banks and governments are working together to create financing tools to fund the green revolution.

By Paula L. Green

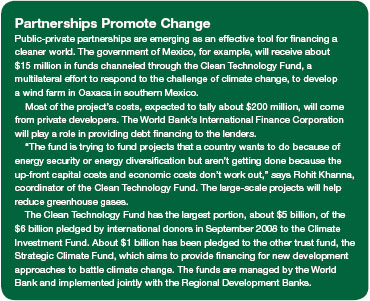

Cajoled, prodded and pushed by presidents, regulators, legislators and international diplomats, multinationals are slowly realizing the time has come to develop programs—and financing vehicles—to reduce their output of carbon and reduce the momentum of climate change. At the same time, the vexed question of where the money will come from to pay for the changes is beginning to be answered with the help of creative financing techniques, innovative public-private partnerships and old-fashioned government stimulus money aimed at helping companies slash their carbon emissions.

Cajoled, prodded and pushed by presidents, regulators, legislators and international diplomats, multinationals are slowly realizing the time has come to develop programs—and financing vehicles—to reduce their output of carbon and reduce the momentum of climate change. At the same time, the vexed question of where the money will come from to pay for the changes is beginning to be answered with the help of creative financing techniques, innovative public-private partnerships and old-fashioned government stimulus money aimed at helping companies slash their carbon emissions.

Industry observers say the ground rules being laid down by national governments and global negotiators, now slogging their way to a successor pact to the Kyoto Protocol, will give banks more confidence to lend money to developers of renewable energy projects and corporations sinking money into energy-saving ventures.

“Assuming that these are healthy banks, I would think that regulatory certainty and support would give confidence and safety to the banks to lend,” says Ethan Zindler, head of North America research for New Energy Finance. He was referring, for example, to the legislation now in 30 states in the United States that requires a portion of electricity to be purchased from renewable energy sources. The potential for a national renewable energy requirement, wrapped in some federal legislation, would reinforce the regulatory certainty for lenders and corporations, he says.

China and India already have used regulatory frameworks to require utilities to buy some renewable power for their energy needs. Europe employs government incentive mechanisms to support the use of alternative energy, such as wind power. The governments of Germany and Spain, the world’s second- and third-largest wind markets, use feed-in or so-called green tariffs to ensure a utility will pay wind farm operators a set price for their electricity. This electricity can be more expensive than electricity generated by other sources.

China and India already have used regulatory frameworks to require utilities to buy some renewable power for their energy needs. Europe employs government incentive mechanisms to support the use of alternative energy, such as wind power. The governments of Germany and Spain, the world’s second- and third-largest wind markets, use feed-in or so-called green tariffs to ensure a utility will pay wind farm operators a set price for their electricity. This electricity can be more expensive than electricity generated by other sources.

In the United Kingdom, the Low Carbon Transition Plan provides financing packages for wind and wave energy and includes changes to planning procedures intended to ensure one-third of the country’s electricity is generated from renewables by 2020.

In the US, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is proposing regulations aimed at reducing the emission of carbon dioxide and five other heat-trapping gases. In April the EPA formally declared the gases to be pollutants that threaten public health and welfare.

|

|

|

David Wyss, chief economist at rating agency Standard & Poor’s in New York, says corporations and their lenders will pay greater heed to national regulations and laws governing the output of carbon emissions, rather than international rules. Yet the international regulations, such as those being negotiated through the Kyoto Protocol, are important. “The international rules provide hope for continuity,” says Wyss, adding that a global framework can provide a level playing field for corporations operating around the planet and not hand a multinational based in one nation an unfair advantage over its competitor on another continent.

An international agreement linked to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Kyoto Protocol’s major feature is the creation of binding targets for greenhouse gas reductions for 37 industrialized nations and the European Union. The pact, adopted in Kyoto, Japan, in December 1997, entered into force early in 2005. The first phase of mandatory emissions reductions runs from 2008 to 2012. A successor pact is now being negotiated, and a global summit is slated for December in Copenhagen.

“Progress at Copenhagen will make a real difference to driving financing toward low-carbon companies and technologies,” says Simon Thomas, chief executive officer at Trucost, a London-based environmental research organization. “Governments will use market-based instruments, such as carbon taxes and cap-and-trade programs, to raise revenues, which in turn will be used to finance carbon-reduction measures and expand green stimulus programs,” he says.

Thomas says leading pension funds and multinationals are already investing in clean energy and other low-carbon solutions. “They are also starting to direct assets towards companies that are more carbon-efficient than their sector peers and stand to gain competitive advantage. This trend will grow as major economies such as the G-8 industrialized nations implement measures to achieve demanding carbon reduction targets,” he adds.

While still behind their European counterparts in addressing carbon reduction, US multinationals are increasingly aware that government efforts to reduce carbon output are here to stay. Some companies have embraced the shift wholeheartedly and look for genuine commercial opportunities while others are accepting the inevitable “begrudgingly,” says Zindler. “Others are in complete denial and still hope the carbon-capping legislation won’t pass,” he adds. The Obama administration supports legislation to reduce carbon emissions through a cap-and-trade program as bills work through both houses of Congress this year. The exact financing mechanisms have yet to be worked out.

Governments Take the Lead

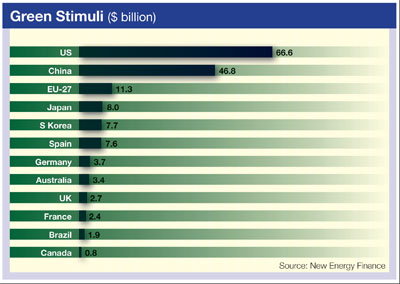

Governments around the globe are supporting the shift toward a cleaner world with an array of stimulus packages that include spending on green technology and investment. According to New Energy Finance, government stimulus programs total $162.8 billion. These include activities directly related to clean energy generation, energy efficiency, grid development and research and development for clean technologies and environmental fuels. New Energy Finance believes that about 15% of the funds will be disbursed this year, with the rest reaching the ground in 2010 and 2011. The US has allocated the largest amount at $66.6 billion, followed by China at $46.8 billion, and $11.3 billion throughout the 27 states of the European Union

The funding mechanisms proposed for global carbon reduction targets include compensating developing countries for the historical damage caused by warming temperatures, such as island states facing rising sea levels that may force the relocation of people. Norine Kennedy, vice president for energy and environmental affairs at the United States Council for International Business in New York, says the funding proposals under consideration include a global carbon tax, a tax on air travel and transport that would go into a global fund, and taking a share of proceeds gleaned when carbon units are sold or traded at exchanges.

|

|

|

“This will have an economic impact on companies of all sizes and all shapes and form,” says Kennedy, adding that the cost is in the trillions of dollars. “The funding needs are astronomical. The commitments are major and will be costly.” The general expectation is that the private sector will pay much of the costs and the fledgling markets in carbon trading and auction allowances will be tapped for funds. In the meantime, corporations are self-financing or turning to banks to finance their energy-efficient measures.

Gregory Efthimiou of Charlotte, North Carolina-based Duke Energy says the company typically self-finances its renewable energy ventures. Duke is the third-largest electric power holding company in the US and makes significant investments in renewable energy projects, including wind, solar and biomass.

John Clapp, a managing director at Citi, says electric utilities will typically raise corporate debt for carbon-reduction measures, particularly when a regulatory commission pre-approves rate recovery for these investments. Even during the banking crisis, a financially healthy multinational in the electric utility sector could go to the corporate debt markets to finance a major capital improvement project, such as energy efficiency or other carbon reduction expenditures, he adds.

“The market has been robust during this time for investment-grade debt,” says Clapp. “There was a flight to quality by investors during the financial crisis, and, as defensive stocks, utilities usually performed well. The markets stayed open, even though the pricing on corporate financings was high compared with recent years.”

Richard Wells, vice president of energy at Dow Chemical, says any carbon reduction program needs to have an acceptable level of payback to make it affordable. “A company knows what it needs to do. It looks for ways to make it affordable,” he adds. Government stimulus money can help, he says. “It can lower the costs of financing and decrease the payback time,” he points out.

Financing remains a sensitive issue. Even BP, which has tried to build a reputation as an environmentally aware energy company and invests about $1.5 billion a year in its alternative energy business, did not want to comment on its financing of energy-efficient projects or the possible business impact of climate change legislation. “We have had to adjust pacing around some of our projects given the current economic climate and relatively low price of crude oil, but we are continuing to invest,” says Tom Mueller, a press officer at the BP America headquarters in Houston.

One financing option for clean energy projects the US congress is considering is the creation of a Clean Energy Bank, which would operate as a quasi-government organization. Possibly modeled on the US Export-Import Bank, it would provide financing mechanisms, such as loan guarantees or low-interest direct loans, to companies investing in clean energy projects.

“The idea is that this would provide a special avenue of financing. There is a void when its comes to providing financing for clean energy technologies,” says Matt Letourneau, a spokesperson for the US Chamber of Commerce’s Energy Institute in Washington, DC.

Bankers are beoming increasingly creative in this area. In the municipal finance market, cities such as Berkeley, California, and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, are considering the issuance of municipal bonds that help them help homeowners carry out energy-saving renovations. “There’s a lot of creative thinking going into this area…with new ideas and approaches going on,” says Clapp. While he does not think the dialogue leading up to Copenhagen was creeping into corporations’ strategic dialogues on electric power, he did think the cost of carbon was now a part of the corporate discussion.

“There’s going to be some form of carbon cost in the US. It’s not a question of whether, anymore; it’s a question of when companies will have to minimize their exposure to carbon,” says Clapp.