UP AND RUNNING

By Dan Keeler

Having regained its footing in the wake of the financial crisis, Angola is now looking to erect a fairer, more balanced economy.

As it continues to rebuild its economy and society in the wake of a 30-year civil war that ended in 2002, Angola is entering a new stage in its development. The general consensus among analysts is that the progress the country has already made since the end of the conflict is nothing short of remarkable. “Just a decade ago Angola was much closer to a failing state than to a proper frontier market, much less anything resembling an emerging market,” says Philippe de Pontet, Africa director at political risk advisory firm Eurasia Group. Now the country is exhibiting all the classic signs of a market that is rapidly emerging: city streets incessantly clogged with traffic, queues of ships trying to enter and leave the country’s main seaport, business-class hotels sprouting like weeds in the nation’s capital and a sense among the populace, impatient to put the last vestiges of the 30-year war behind them, that economic development can’t happen soon enough.

As it continues to rebuild its economy and society in the wake of a 30-year civil war that ended in 2002, Angola is entering a new stage in its development. The general consensus among analysts is that the progress the country has already made since the end of the conflict is nothing short of remarkable. “Just a decade ago Angola was much closer to a failing state than to a proper frontier market, much less anything resembling an emerging market,” says Philippe de Pontet, Africa director at political risk advisory firm Eurasia Group. Now the country is exhibiting all the classic signs of a market that is rapidly emerging: city streets incessantly clogged with traffic, queues of ships trying to enter and leave the country’s main seaport, business-class hotels sprouting like weeds in the nation’s capital and a sense among the populace, impatient to put the last vestiges of the 30-year war behind them, that economic development can’t happen soon enough.

The dense traffic and congested ports are clear signs of another classic emerging markets phenomenon: overstretched infrastructure. In Angola’s case, it is hardly a surprise. “The civil war destroyed the country’s infrastructure,” de Pontet explains. “The country started from a base of zero.” This assessment is no exaggeration.

During the three decades of ferocious fighting, Angola’s roads, railways, agricultural infrastructure and its power and water supply systems were devastated. What had once been one of Africa’s most fertile and prolific food exporters was no longer able even to feed its own population, supporting itself only on the revenues from its burgeoning offshore oil industry.

FUNDING INFRASTRUCTURE

In the aftermath of the war, though, it was oil that the government was able to use to jump-start the country’s redevelopment. It did this partly by building a relationship with China, says de Pontet. “China really was the only option at the time, as Angola was unable to access other significant funding, so the country carried out a series of multibillion-dollar infrastructure projects that were effectively paid off with oil exports,” he explains.

A decade on, China is still funding infrastructure, although European development institutions are also now playing a part, and the Angolan government is investing heavily in construction, particularly for transportation and sanitation projects. The results, according to Roger Ballard-Tremeer, honorary CEO of the South Africa-Angola Chamber of Commerce and South Africa’s former ambassador to Angola, are impressive, with key transportation links outside the capital, Luanda, having been restored and improved: “The rehabilitation of the three railway lines advanced well during 2012, making it increasingly possible for inputs to move into the hinterlands and outputs to move toward the ports on the Angolan littoral,” he notes. “These ports reached a level of functionality not seen for more than 40 years.” And domestic air services now allow travel relatively quickly to, from and between all eighteen Angolan provinces, he adds. “Angola’s international connections improved, too.”

In parallel with its efforts to rebuild the country’s transportation systems, Angola’s government is working hard to regenerate its agriculture sector. With some of the most fertile land in the region, the sector is attracting considerable interest from foreign companies eager to help the country regain its role as the breadbasket of Southwest Africa. As well as providing opportunities for foreign investors, the push to develop Angola’s agricultural capacity should produce long-term benefits for the country’s population and its economy, says Nicolaas Alberts, a director at Investec Asset Management in South Africa. “Currently, almost all food is imported, so increasing domestic agricultural output should bring down prices, as well as boost incomes in rural areas.”

|

|

Swanepoel, Daniel John Consulting: Social tensions will remain for a while—which may not be a bad thing as it reminds the government of its promises |

Standard Chartered Africa economist Victor Lopes says the progress Angola is making is a testament to the government’s commitment to rebuilding the country: “Each year around $8 billion to $10 billion in government investment is directed toward capital projects,” he says. But even so, it is unclear whether Angola’s infrastructure development can keep pace with economic development. Daniel Swanepoel, managing director of Daniel John Consulting in South Africa, notes: “The reality is that the country is experiencing exponential growth,” he notes. “It would be difficult for any country in this position to keep up.”

GROWING CONFIDENCE AND CREDIBILITY

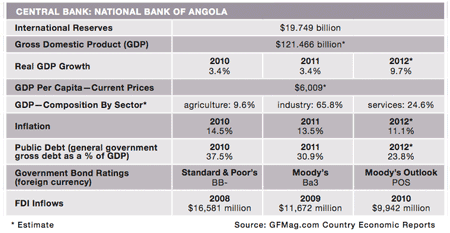

In its January 2013 report on Angola’s efforts to diversify the economy, the IMF offered a resoundingly positive assessment of the country’s progress: “In 2012, Angola attained robust economic growth, a stronger fiscal position, single-digit inflation, a further buildup of international reserves and a stable exchange rate,” the report stated. Estimating last year’s real GDP growth to have been more than 8%, the IMF noted that “non-oil sector growth, bolstered by a scaling-up of the public-sector investment program aimed at completing reconstruction and addressing key infrastructure gaps, is expected to exceed 7% in 2013.”

Coupled with the administration’s efforts to create a more business-friendly and transparent environment, such robust growth figures are attracting the attention of a wider range of international companies than historically considered investing in Angola. “Angola is very market-friendly, investor-friendly and politically stable,” says Vincent Darracq, Angola analyst for risk consultancy Control Risks. “Now the government is trying to attract investment in [non-oil] sectors such as construction and food production, providing substantial tax incentives that could ensure those sectors present interesting opportunities over the next 10 years.”

The IMF—which has been involved with Angola since 2009, when it helped Angola cope with the fallout from the global financial crisis—has endorsed the government’s economic policies, thus boosting Angola’s credibility among potential investors. Investec’s Alberts adds: “With the IMF and the likes of the big four accounting firms being involved, it pushes institutions to be more transparent, so whatever inefficiencies there were before, they will become less over time.”

However, investing in Angola still involves considerable risk, says Ryan Hoover, portfolio manager at Africa Capital Group. “Angola, in essence, remains a kleptocracy. Corruption is rampant, and Angolan law requires that multinationals contract a certain percentage of their business with Angolan firms, which are typically owned by government officials,” he comments.

Darracq argues that focusing too closely on the risk could lead companies to miss out on potentially valuable opportunities: “Companies are right to be cautious about investing in Angola, but that caution should not be overdone. Angola provides plenty of opportunities in terms of investment, and the opportunities are so big they shouldn’t be ignored.”

REVERSING THE RESOURCE CURSE

One of the key challenges facing Angola’s leaders is how to translate headline economic development into long-term stability and prosperity for the general population. Angola has long been cited as a textbook victim of the so-called resource curse, where much of the country’s wealth is controlled by the ruling elite and their cronies while the vast majority of the population continues to struggle in poverty. “Some of Angola’s poor and forgotten remain very dissatisfied with the wealth imbalance, and this is exacerbated every time reports emerge in the national and international media about the increasing wealth of a few apparently privileged Angolans,” says Ballard-Tremeer. However, the government’s 2013–2017 economic plan is focused on creating a more equable society, he notes, and “initial indications suggest that this could happen fast if the 2013 budget rolls out as planned.”

“Just a decade ago Angola was much closer to a failing state than to a proper frontier market, much less anything resembling an emerging market.”

–Philippe de Pontet, Eurasia Group

Having created a stable economic platform, Alberts says, the government is now “reducing imports, spurring manufacturing and creating better conditions for education and health with a focus on improving opportunities for young people.” And although in many countries stark inequality has fostered widespread unrest of late, few expect Angola to witness any kind of violent uprising. Swanepoel believes that protests could actually be healthy for Angola: “A growing number of people are rising into the middle class, but it is too slow a process. Social tensions will remain for a while—and perhaps that is not a bad thing as it reminds the government of its promises.”