With a hefty debt overhang, Portugal can’t quit now on structural reform.

Portugal dodged a fiscal bullet when Canadian rating agency DBRS confirmed its ranking on April 29 at BBB stable. Thanks to that sole investment-grade rating, the nation continues to qualify for access to the European Central Bank’s (ECB’s) bond-buying program, which helps keep down government borrowing costs. “The country is holding on by a thread,” says Antonio Barroso, senior vice president at Teneo Intelligence, “with only one investment-grade rating to keep a lid on bond price volatility.”

Portugal must finance its deficit by raising funds in bond markets. “If interest rates rise, it requires more resources to make those payments,” adds Diego Iscaro, senior economist at IHS Global Insight. He points out that higher government interest rates also affect commercial credit rates, not to mention overall confidence.

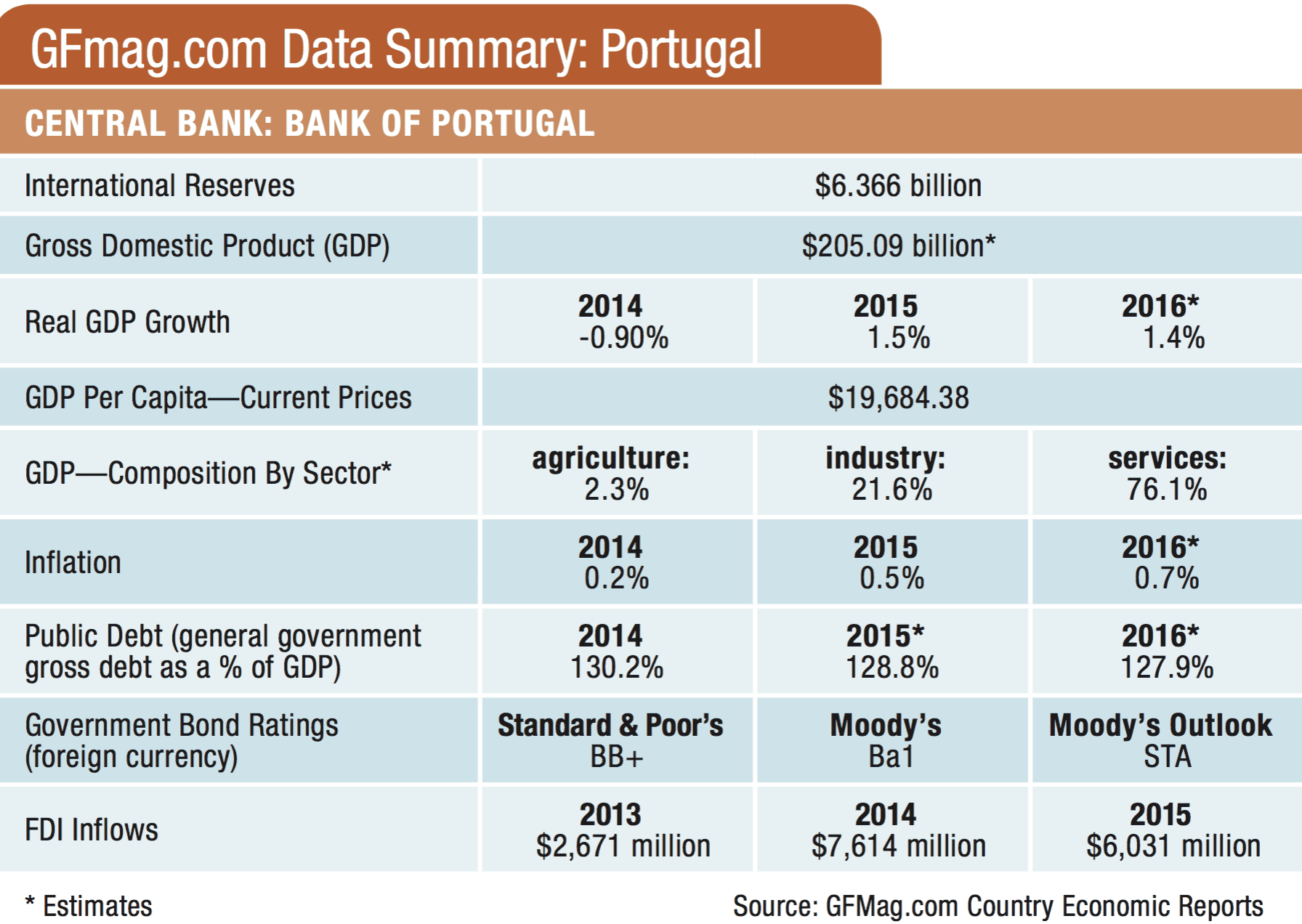

Considering that public debt reached almost 129% of GDP at the end of 2015, a future rating downgrade might create a precarious funding risk. “Portugal still needs further fiscal adjustment because government debt is running so high,” notes Adriana Alvarado, DBRS’s lead analyst on Portugal.

The Primary Challenges

Despite progress in recent years, Portugal faces serious headwinds, particularly in the form of public and corporate indebtedness, fiscal imbalances and anemic potential growth. Although many structural reforms have been implemented, insufficient competition and labor inflexibilities pose concerns. Another disappointment: “Investment has so far failed to maintain a sustained recovery, decelerating in the second half of 2015,” according to Rui Constantino, chief economist at Banco Santander Totta. He notes a context of increasing uncertainty about world growth and underutilized capacity.

At Capital Economics, European economist Jack Allen pegs the deficit at about 3% of GDP for this year, and 2.5% for 2017. If GDP slows, as he expects it will, debt reduction will become an even greater burden. Both the deficit and public debt load may decline only gradually. Alvarado regards current deficit targets as “ambitious,” characterizing growth assumptions over the medium term as “optimistic.” Although the government officially projects almost 2% by 2020, “we think 1.5% more likely,” she says. Her caution echoes IMF forecasts for average growth of 1.2% over the period. Meanwhile the government hopes to chip away at the fiscal deficit through a reduction in expenditures but has so far demonstrated a weak track record on cuts.

As an open economy, Portugal is dependent on other nations—Europe primarily, but other parts of the world, too. Although the government previously looked to exports for support, it is now trying to expand the share of private domestic consumption to boost GDP, which will likely mean higher imports.

However, some of Portugal’s traditional export markets are now laboring under their own pressures. Angola, a long-term trading partner, has been impacted by low oil prices. “A natural effect is less money available to invest in Portugal and an unwillingness to let dollars out of the country,” suggests Carlos Jesus, equity researcher at Caixa Banco de Investimento. Brazil, another export market, is also confronting lower commodity prices, as well as higher inflation, a large fiscal deficit and political upheaval.

Ongoing political uncertainty may constrain the Portuguese minority government’s ability to adopt additional reform measures. The Socialists, in power since November 26, are supported by two smaller left-wing parties. “Socialists would never normally have cut a deal with the left, with antagonism going back to the Carnation Revolution in 1974,” notes Barroso. Yet differences between the Socialists and the “left bloc” represent more style than substance. The current government has already “rolled back on some measures, like pay cuts for civil servants, but in reality, the previous right-wing coalition had already planned those,” Barroso points out. The main distinction is the time frame, which will now be faster. Notwithstanding, disagreements between the Socialists and their left-wing allies could still emerge, potentially over the next budget in October 2016. Early elections, should they take place, would add to the unpredictability.

Health Of The Banking Sector

The banking sector casts another shadow. More than 12% of loans are considered nonperforming, being at least 90 days behind in interest payments. “Deterioration among financial institutions, which might require a public bailout, could fuel concerns over the strength of the government balance sheet,” Allen warns. If economic growth slows, the damage could seep into the vulnerable banking sector. Labeled a “doom loop,” such negative feedback carries even graver repercussions of contagion to elsewhere in the eurozone.

Portuguese banks remain fettered to a large stock of poor-quality legacy assets, with resources directed toward low-productivity firms. There is an urgent need now to take action to strengthen the sector by measures such as reducing operating costs, divesting unprofitable assets, creating capital buffers, bolstering balance sheets and improving structural liquidity.

“Consolidation and restructuring are the only alternatives for banks that need to recapitalize,” says Jesus. Two shocks from December 2015 highlights the process: The majority of assets and liabilities of Banif were transferred to Santander Totta, protecting senior bondholders and depositors, while imposing a fiscal cost to taxpayers of 1.2% of 2015’s GDP. A week later, senior debt obligations valued at €2 billion ($2.2 billion) were transferred from Novo Banco to its predecessor BES, to shore up Novo’s capital.

Unhealthy banks are not able to support economic recovery. Corporate indebtedness precludes the distribution of credit to the most productive areas. “We are in a transformational stage,” Jesus explains, “so although the ECB prints money, the funds do not end up in the mainstream economy.”

Where Are We In The Cycle?

Observers note dawning glimmers in the overall picture, but the question is whether these improvements can be sustained. The budget deficit is on a downward trajectory, plunging from 7.2% of GDP in 2014 to 4.4% in 2015. However, one-off measures to prop up the banks augmented the 2014 deficit by 3.7%, and the Banif rescue in 2015 by 1.2%. On May 3, the European Commission (EC) lowered its structural deficit forecasts to 2.2% for 2016 and 2.5% for 2017.

Green shoots are budding on many fronts. Rising inflation could prove a net positive, if it helps to erode the high debt overhang. Unemployment has fallen from 17.7% in 2013 to 12.1%, and economic sentiment peaked at a 12-month high this spring. Structural reforms continue apace, fine-tuning and targeting the labor market and social security and eliminating red tape.

Exports continue to flow at a good clip, helping to balance the current account. Pre-crisis export share constituted 30% and has now culminated in a 41% weight of GDP. Goods and services, notably tourism, have contributed to the expansion. “Despite the adverse effects from the decline in sales to Angola and other emerging markets, Portuguese companies have been diversifying their export base to other countries, such as Western and North Africa,” Constantino notes.

“Portugal is benefiting from a very benign macro environment, but what happens when there is a reversal and you lose some of those benefits?” Barroso asks. Nobody knows. So far, the country has been buoyed by the same macro factors that have been supporting the rest of Europe, including low interest rates, a weak euro to advance exports, and rock bottom oil prices, which gave households and firms more spending power. At the same time, the consumer recovery was driven by a decline in household savings, which is not sustainable. Allen predicts that “the boost to growth deriving from the weak euro and low oil prices will start to fade this year. Nor do we expect consumers to spend such a large share of their income, which amounted to 90% in 2014 and 95% in 2015.”

Hard work lies ahead, to consolidate the progress made and keep the country moving on a successful path. High on the list are efforts to improve bank profitability. Soon the government should sell Novo Banco, which was recapitalized with funds from both the state and senior debt holders. “It’s important to recover as much money as possible, so other banks don’t take a hit,” says Barroso.

Ongoing structural reforms must be maintained to address wage flexibility, hiring and firing, lifelong learning, competiveness, public administration, the judicial system and pension reform. Results are beginning to take root: It now takes less time (under three days) to start a business in Portugal than in any other European country. Quality infrastructure and tax cuts for SMEs are also building a platform to revive the economy.

The administration still needs to promote domestic consumption. Some of that encouragement could be subtle, Jesus suggests—a matter of “steering expectations and stating intentions.” The ultimate task is a balancing act. “If the government loosens fiscal policy too much,” Allen says, “it will create a first-round boost to the economy, but it may damage perceptions of its willingness to implement economic reforms.” Already the planned modest fiscal expansion, just half a percentage point of GDP, is enough to worry the EC. Over the next round, tensions are inevitable between fiscal discipline and the pressure keep expansion alive.