REFORM BECOMING REALITY

By Laurence Neville

After years of promises, there are tentative signs that Russia is finally getting serious about reforming its economy.

Russia has always been the odd one out in the BRIC quartet of leading emerging economies. While Brazil, Russia, India and China have enormous geographical size in common, the dynamism and rapid growth of the Southern Hemisphere economies have set them apart from Russia. Its role in the global economy has been simply to exploit its oil, gas and mineral wealth: Oil products, gas and metals account for 80% of Russian exports, while oil and gas revenues account for half of federal budget revenue.

As a result, the non-oil budget deficit is still relatively high at 10% to 11% of GDP. “Oil and gas is the major supporting driver of the Russian economy,” says Olga Fedotova, credit analyst at UniCredit. “When we say Russia, we mean oil and gas.”

Given flat oil prices, the dominance of the sector took its toll on the economy in 2012. According to the World Bank, Russia’s economy grew 3.4% in 2012, down from 4.3% in 2011. Although these figures are impressive compared with many developed economies, Russia remains the poor relation of the BRICs.

Evgeny Gavrilenkov, chief economist at Sberbank, points out that Russia’s economy has demonstrated its ability to grow using domestic sources, despite global turbulence and capital outflow. “The effectiveness of the economy is moderately improving: The total increase in labor productivity over the first nine months of 2012 was 3.1%,” he says. Nevertheless, he concedes that “2013 will be another year of muddling through.”

In the long term, the Russian economy requires revitalization to accelerate growth. The challenges are formidable. First, Russia must step out of the shadow of its oil and gas industry. Second, it must seek genuine reform and crack down on corruption, political meddling in the economy, dismal corporate governance and what many see as a disregard for property rights and the rule of law.

In their recent Russia Focus report, Benoit Anne, head of global emerging markets strategy at Société Générale, and Vladimir Kolychev, chief economist at SG-owned Rosbank, say that Russian authorities have established an encouraging reform plan. “Apart from committing to a more comprehensive set of macroeconomic policies (inflation targeting and budget rules), some progress has also been made in other areas,” they note.

For example, measures to improve corporate governance at state-owned companies were announced. Perhaps more important, decrees from president Putin have set a goal of improving Russia’s position in the World Bank’s Ease of Doing Business ranking from 120th to 20th by 2018.

|

|

Shemetov, Moscow Exchange: Investors can now trade Russian government bonds as they do securities the world over |

“The government, together with the Agency for Strategic Initiatives, has started to work on a dozen roadmaps to improve the business climate in different sectors of the economy,” note Anne and Kolychev. “Some of these have already been approved despite pressure from vested interests.” Administrative reform is also in the pipeline, while an ongoing anti-corruption campaign seems to be gaining ground.

One of Russia’s greatest reform success stories is its financial market infrastructure. A Central Securities Depository (CSD) was launched on November 6, 2012, satisfying the requirements of US SEC Rule 17f-7 and enabling more US institutional investors to access the market. Another boost for international investors is the creation of foreign nominee accounts: Custodians can now manage documentation on investors’ behalf.

“There will be changes in the level of market activity in Russia following the introduction of these reforms—ease of access is a crucial consideration for investors,” says Alex Krunic, head of product sales for direct custody and clearing at J.P. Morgan.

Meanwhile, the mechanics of the market have also been streamlined. In March, Russia moved to a conventional settlement cycle of T+2 [transaction date plus 2 days] for the 20 most liquid equities and 39 government bonds. “The entire market is expected to move to T+2 by January 2014,” notes Krunic. T+2 trading means investors no longer have to pre-fund their trades, which should increase willingness to trade—and thus liquidity.

Another logistical boost comes from links between the CSD and Euroclear’s and Clearstream’s settlement systems. “An investor in London or New York can now trade Russian government bonds the same way they trade other securities the world over,” notes Andrey Shemetov, deputy chairman at Moscow Exchange.

The reforms to date were thought impossible until a few years ago. However, there is still plenty to do. “The next step for Russia is to build a solid domestic investor base and an effective system of market makers to generate liquidity and effective pricing,” says Jan Dehn, chief strategist at emerging markets investment house Ashmore. Krunic agrees: “Russia does not allow pension funds to hold domestic equities, and assets are primarily held in fixed-income instruments. Changing these rules is on the agenda and will be beneficial.”

One area that remains uncertain is Russia’s $100 billion privatization drive, announced three years ago. The list of privatization candidates is long— plans include up to 5% of Russian Railways (previously expected in 2014), 25.5% of leading bank VTB, 7% of diamond miner Alrosa, and up to half of Russia’s largest shipping company, Sovkomflot. Around 6% of oil company Rosneft could also be sold.

|

|

Gavrilenkov, Sberbank: The economy has shown its ability to grow domestically, despite global tumult and capital outflow |

However, since president Putin reassumed the presidency, most observers believe privatization momentum has slowed. Moreover, an insistence on focusing share sales on the domestic market could yet scupper any deals that do make it to market.

Moreover, in the oil sector, state ownership has increased from 5% in 2002 to more than 50% in 2013 following the Rosneft–TNK-BP acquisition, notes UniCredit’s Fedotova. “Rosneft has been the major consolidation vehicle, taking over a considerable number of assets from private owners, such as Udmurtneft, Yukos and Itera, and it is planning to swallow TNK-BP to become the world’s largest public oil company,” she adds.

While privatization is important to increase efficiency, it also sends a broader signal about the government’s role in the economy. Likewise, government must send a signal about the importance of entrepreneurial spirit in the Russian economy if it is to lessen its dependence on oil and gas, according to Axel Tillmann, CEO of RVC-USA, US subsidiary of a $1 billion Russian fund of funds. He says that having joined the WTO, Russia is steadily reforming its internal system, including the legal environment. But “a conversion from oil and gas cannot be achieved overnight: It’s a 20-to-25-year process,” says Tillmann.

The potential opportunities are sizable. “Russia could overtake Germany to become the largest European economy before 2020 in PPP terms and by around 2035 at market exchange rates,” according to John Hawksworth, head of macroeconomics at PwC and author of the World In 2050 report. If Russia were to truly embrace reform, it might finally earn its place as a member of the BRICs.

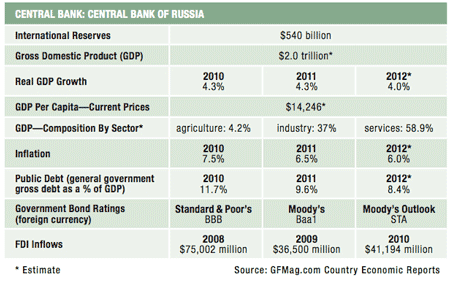

GFmag.com Data Summary: Russia