GREAT EXPECTATIONS

By Justin Keay

The government has lofty aspirations for Turkish growth, but reform and demographic development are necessary for the nation’s economy to reach its potential.

The coming year could be a good one for Turkey. And the next decade has the potential to be great. But slowing growth and a need for domestic reforms could hamper the country’s promise.

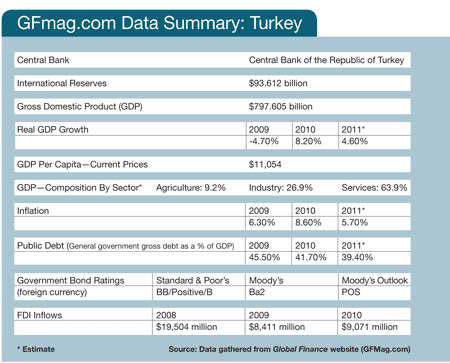

Ten years after the Justice and Development Party (the AKP) and prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdoan won their first election, the former sick man of Europe is an economic powerhouse. Living standards have improved dramatically, with GDP growth consistently one of the highest in the developing world. And its neo-Ottoman foreign policy has made it a diplomatic and trading force to be reckoned with, especially with near neighbors in the former Soviet Union and Arab world. Turkish pride in achieving GDP growth of above 8% in each of the past two years—at a time of unprecedented global crisis—has been reinforced by awareness of the eurozone’s anemic growth and the economic tsunami engulfing its historic rival, Greece.

But right now international investors seem off-key on Turkey. Growth is slowing markedly, with 2% to 3% at best—and some estimates as low as 0.4%—projected for 2012, while inflation remains around 9%, fueled by the rising price of energy imports on which Turkey is so dependent. The current account deficit is seen as even more of a headache, at $77 billion last year, or around 10% of GDP (against 6.5% in 2010), again reflecting high-cost energy imports but also the excessive domestic consumption of recent years (credit growth last year alone increased over 30%).

These and other problems, including the possibility of a protracted domestic political debate on the new civilian constitution—Turkey’s first—and the Syrian crisis, have led many analysts to write down Turkey’s prospects for 2012.

A PERFECT STORM

A swath of reports suggests the onset of a “perfect storm,” with Turkey buffeted by a deteriorating global economy leading to tighter international capital markets, on the one hand, and the need to cool an overheated domestic economy yet keep growth and employment rising, on the other. Some analysts suggest the Turkish growth model depends on abundant global liquidity and that when times are uncertain, some investors turn away.

“Right now, Turkey really isn’t flavor of the month. Markets prefer energy exporters, while the assumption is that despite the authorities’ efforts, growth will suffer as credit and consumption slow alongside efforts to rein an unsustainable deficit,” says Charles Robertson, global chief economist and head of macro strategy at Renaissance Capital.

Other negative news has also had an impact on investor appetite. In early 2012 rumors were circulating about Erdoan’s health after he had two major intestinal operations in November and January. The concerns reflect how the AKP is still very much a one-man show with Erdoan’s forceful personality holding the competing factions of the movement together. President Abdüllah Gul, deputy prime minister Ali Babacan and foreign minister Ahmet Davutolu have all been proposed as successors, but none have Erdoan’s deft political skills or popular appeal.

“The central bank seems to be doing everything except what the market expects it to do—which is raise interest rates”

– Wolfgango Piccoli, Eurasia Group

There have also been concerns about the independence of the central bank. Some observers say it appears to be following government policy in promoting growth over all else, even reversing an interest rate rise earlier this year against market expectations. Numerous measures have been passed in an effort to cool the economy—including increasing interest rate spreads and allowing the Turkish lira to depreciate against leading currencies. But many observers remain unconvinced of the effectiveness and impartiality of the central bank’s monetary policy management.

“The central bank seems to be doing everything except what the market expects it to do—which is raise interest rates,” says Wolfgango Piccoli, Europe head at geopolitical research firm Eurasia Group.

REFORM OFF TRACK

Meanwhile there is a sense that the government’s once-ambitious reform program, pivotal to the AKP’s first two terms in office, has petered out. Piccoli blames this on tiredness and a false sense of security generated by the fact Turkey has done better than other countries in recent years.

With EU accession now on the backburner—no new chapters are scheduled to be negotiated and Ankara has said it will freeze diplomatic relations with Brussels when Cyprus assumes the rotating presidency in July—the stimulus for reform is not there. “If you look throughout Turkey’s history, reforms have only happened when there has been external pressure. With both the EU and IMF now out of the picture, there really isn’t any,” Piccoli argues.

This matters because international perception is vital if the country is to be able to successfully tap international markets for funds. William Jackson, Turkey analyst at London’s Capital Economics, estimates that Ankara needs to rein in the deficit by 50% for it to become sustainable.

Jackson warns that Turkey remains vulnerable to increasing global risk aversion if the eurozone crisis comes back fully into market focus. “Turkey would be one of the most vulnerable economies to financial contagion,” he says.

THE BIGGER PICTURE

Some analysts note, however, that the current downsides must be seen in perspective. Growth will likely fall off this year, and the current account deficit is a major concern, but Turkey still looks pretty good compared with most other OECD countries.

In fact, the OECD has said the country will be among the fastest-growing of its members over the next few years, with growth averaging 6.7% between 2011 and 2017. And the business environment has improved dramatically in recent years, boosting foreign direct investment inflows. Last year saw FDI inflows reach close to $16 billion—a 76% increase on 2010.

“FDI is one of the healthiest ways to finance the current account deficit,” says Ilker Ayci, head of Ispat, Turkey’s investment promotion agency. He says Ispat is prioritizing foreign investment in import-dependent sectors in an effort to promote import substitution and exports.

According to the IMF, Turkey will attract more than $111 billion of FDI over the next five years. “We have developed strategies focusing specifically on major FDI source countries and critical sectors, and we also laid out several shortlists of specific target companies,” Ayci notes, pointing to the government and private sector’s formation of the Coordination Council for the Improvement of Investment Environment (YOIKK). “This is an excellent platform for partnership, where stakeholders identify and remove regulatory and administrative barriers holding back both international and domestic investment,” Ayci says.

STRONG BANKING SECTOR

For those concerned about stability, Turkey’s banks are another cause to be upbeat. Although this year is expected to see a slight rise in risk aversion following the downturn in global business confidence, the sector remains well capitalized. Turkey’s growing economy and population also mean there is still good potential for a further expansion in activity.

|

|

Bali, Isbank: The Turkish banking sector has huge potential for domestic growth |

“Penetration rates of the basic banking products still lag those in the developed countries. However, increase in our national income, our young population and rising use of technology indicate that there is high growth potential,” says Hakan Binbagil, CEO of Turkey’s Akbank. For those within the banking industry, the fact that the sector survived the global crisis of 2007–2008 so strongly is proof of its underlying strength. It was the only OECD country not to require state support of its bank sector.

Binbagil points to the banking sector’s average NPL ratio of 2.8%—down from 5.4% in 2009—average capital adequacy ratio of 16.8% and no underlying balance sheet problems. He also says that banks are increasingly playing an active and constructive role in the economy, with loans forming a growing part of banks’ asset structures—government bonds are now just 24% of assets against 43% nine years ago—and the countries’ banks continue to invest in new technologies. The opportunities for banks to enhance their contribution to the economy remain considerable, particularly by increasing loans to SMEs, which remain low.

Adnan Bali, head of Isbank, agrees that banks have more room to invest domestically, stressing the huge potential of Turkey’s banking sector as the country converges with the EU. “According to end-2010 results of EU-27 countries, the loans-to-GDP ratio was 152%, deposits-to-GDP ratio was 148%, and the total-assets-to-GDP ratio was 365%. For Turkey, it is anticipated that loans and deposits over GDP ratios will reach 65% to 70% levels and banking sector total-assets-over-GDP ratio will exceed 100%,” he says.

ASSET GROWTH

Turkish banks are expanding their branch networks and growing assets. Isbank, for example, forecasts a 15% to 17% growth in the loan book and deposit growth of 10% to 12% this year over 2011. Net fees and commissions are expected to grow by more than 10%, and the bank anticipates that asset quality will remain stable.

“We aim not only to expand in our core market but also to explore growth opportunities in the geographies where our clients are active,” says Bali. “We seek to be a regional bank first and then a global player.” He says the bank is planning new initiatives in Iraq, Georgia, Kosovo, Pakistan, Azerbaijan and Egypt.

For banks and the government, growth remains crucial. With the workforce expanding at around 750,000 a year in a country where the average age is just 28, Turkey needs growth of 7% just to stand still in employment terms. Mert Yildiz, Turkey analyst at Renaissance Capital, says the economy needs to become more export-focused and internationally competitive: He argues that the country’s only undisputed success is auto products. It also needs to boost savings, which remain pitifully low, leaving Turkey too dependent on international financing.

DEMOGRAPHIC DEVELOPMENT

With such a rapidly expanding population, much more attention must be focused on the education system and on boosting labor participation, according to Yildiz. For example, only 25% of Turkish women of working age work versus a European average of 55%. “Look at the latest list of the world’s top 100 universities: There isn’t one Turkish institution there,” Yildiz notes. “And the average citizen has just 6.5 years of proper education. That is far too low for an economy with such ambitions.”

Nonetheless the government’s ambitions remain undimmed. “Turkey aims to be one of the 10 largest economies of the world by 2023, with a GDP of $2 trillion and an export volume over $500 billion,” says Ispat’s Ayci. It also aims to invest in infrastructure and boost Istanbul’s appeal as a global financial center.

Given what the country has achieved over the past 10 years, there is little doubt that Turkey is capable of reaching the lofty goals set by the current administration—provided reforms continue and underlying problems are tackled.