ENGINEERING THE NEW TURKEY

By Justin Keay

Major infrastructure investments and improved economic strength are just two of a number of positive developments to come out of Turkey in the past year.

Ankara stunned investors in February by scrapping its $5.8 billion sale of a 25-year concession to operate some of the country’s busiest toll roads and bridges. Halting one of Turkey’s biggest-ever privatizations naturally upset would-be buyers Koç Holding—a leading local business conglomerate—and Khazanah, Malaysia’s sovereign wealth fund. But the decision had full support from prime minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, who believed the price should have been $7 billion.

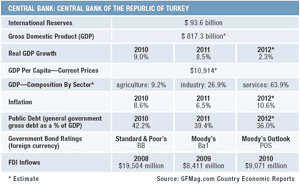

A few years ago, this scenario would have induced a run on the markets and the Turkish lira as investors questioned Ankara’s reform commitment and Turkey’s relative appeal as an investment destination. Today the main legacy of Erdogan’s cancellation is a reminder of his authority and a nagging feeling he might have a point about the price. For although GDP growth has slowed and economic concerns remain—about the current-account deficit in particular—Turkey remains a powerhouse with excellent prospects, compared with the rest of Europe. And despite the fact that growth slipped to around 2% last year, the government is forecasting 4% this year, fueled by rising domestic demand and construction.

“We expect 4%-to-5% growth, which Turkey should be able to sustain: This is needed if the economy is to create 700,000 new jobs a year, the level required to maintain employment levels,” says Naz Masraff, Turkey analyst at the Eurasia Group consultancy in London.

Underlying this expectation is the belief by many Turks that their country—once dismissed as the sick man of Europe and characterized by inflation, corruption and general failure—can now teach the world’s advanced nations a trick or two.

|

|

Ozkaya, Odeabank: Local banks have the capacity to underwrite multibillion-dollar deals with no need to syndicate at all |

Turkish firms and contractors have been big winners in Iraq. Exports have increased by 25% a year over the past few years to reach almost $11 billion in 2012, making Iraq Turkey’s second-biggest market after Germany, with sales expected to continue rising as Iraq stabilizes and grows more wealthy. In Libya and elsewhere too, Turkish companies are well ahead of Western competitors in building business relationships and getting contracts.

Separately, a formal truce in the 30-year war with the Kurdish PKK—which has killed some 35,000—was announced on March 21. The hope is that Turkey’s 15 million Kurds will now receive full cultural rights ahead of a national vote on a new constitution and that Kurdish Southeast Turkey will see much-needed new investment. And an ongoing rapprochement with Israel has raised hopes that Turkey, along with other countries in the region, will soon begin developing the large sub-sea energy reserves reported within the Levant Basin.

Support for joining the EU—once 75%—has fallen. Polls now suggest that just a third of Turks want to join an organization that has always viewed Turkey with ambivalence.

HEIGHTENED MOOD

The national airline is emblematic of the new mood. Once a byword for shoddiness, Turkish Airlines was recently crowned Airline of the Year by a leading global industry newspaper. Having posted record profits of $1.1 billion last year, it will buy 117 planes from Airbus and plans to fly to 300 destinations by 2015, with a strong focus on the Middle East and the ’Stans, which Ankara sees as a near-abroad destination.

Privatization has moved forward. In March four power distribution companies were sold for $3.5 billion, following open bidding between 16 interested companies. These sales mean Turkey has raised $8.5 billion from asset sales in three months, compared with $7.5 billion over the past three years.

“Despite recent growth, low penetration rates in fundamental banking products imply significant, inherent growth potential. There are still around 18 million unbanked people here.”

– Alper Hakan Yuksel, Akbank

Banks are doing well in this buoyant environment. Consolidated net profits at Akbank last year rose some 19% to 3 billion Turkish lira ($1.7 billion), with over 1,000 new employees added to its workforce (bringing the total to over 16,500). It plans to open 50 new branches this year and expand loan volume by 20% a year between now and 2015—to around 160 billion Turkish lira. “The sector remains well capitalized, robust and profitable. Despite recent growth, low penetration rates in fundamental banking products imply significant, inherent growth potential. There are still around 18 million unbanked people here,” says Alper Hakan Yuksel, Akbank executive vice president in charge of corporate banking.

Ilker Ayci, head of Ispat, Turkey’s investment agency, echoes this assessment. “The Turkish banking sector has attracted over $31 billion in FDI over the last decade. More importantly, it has been one of the most resilient during the recent global financial crisis,” he argues, pointing out that not one local bank has required bailing out.

Indeed, the sector is attracting banks from abroad. Last year the Bank of Tokyo Mitsubishi—Japan’s largest—and Lebanon’s Bank Audi both received licenses to begin full-scale operations. The latter established Odeabank with nine branches. It intends to open another 23, aiming eventually to have 100 branches across the country.

“The question for us was never ‘Why Turkey?’ It had always been ‘Of course Turkey.’ It was just a matter of when,” says Odeabank’s general manager Huseyin Ozkaya. He argues that one of the reasons Turkey’s banking authorities are now keen to attract new entrants into the market is to boost competition, not least for customer deposits, as part of the wider strategy of encouraging domestic savings.

INFRASTRUCTURE GROWTH

Another reason is Turkey’s ambitious infrastructure plans. Ozkaya reckons the investment needed for the next five years will be even greater than $30 billion, particularly if new roads, hospitals and power plants—demanded by an increasingly wealthy population—are to be financed in addition to a new airport and bridge for Istanbul, new motorways and ports. He says much of this will be financed locally.

“Local banks currently have the capacity to underwrite multibillion-dollar deals with no need to syndicate at all,” Ozkaya argues. “The lack of international interest forces local banks to absorb this increasing funding demand. I do not think these dynamics will change in the next five years.”

Akbank’s Yuksel says that the sheer size of many projects—the third airport for Istanbul is expected to cost up to $10 billion; the third bridge across the Bosphorus, $2.8 billion; and the new Gebze-zmir motorway up to $6 billion—means many banks will need to be involved. He says the majority of the infrastructure projects will be organized through BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) schemes.

In addition, developing the Ministry of Health’s ambitious plans to create 36 integrated health centers across the country through public and private partnership schemes is expected to cost at least $15 billion. Yuksel believes the financing will mainly be arranged via Build-Operate-Lease schemes. The challenge will be to find long-term foreign participation in these projects, something that should be made easier with the improvement in Turkey’s credit rating and new regulations regarding the issue of lira-denominated bonds.

VOLATILE FOREIGN FLOWS

Despite Turkey’s huge business potential, challenges remain. Economic concern persists over inflation—which at 6% is higher than that of most of Turkey’s trading partners and thus affects competitiveness—and especially the current account deficit.

“The good news is that Ankara cut the deficit last year from 10% to around 6%. The bad is that domestic demand is rising, fueling import demand. This could undo much of the recent good work,” says William Jackson, Turkey analyst at Capital Economics in London.

“We expect 4%-to-5% growth, which Turkey should be able to sustain. This is needed if the economy is to create 700,000 new jobs a year, the level required to maintain employment levels.”

– Naz Masraff, Eurasia Group

He and others voice fears that, despite the increasing sophistication of Turkey’s financial sector, the country remains too dependent on foreign money, much of it short-term and thus potentially volatile. Although the government made a start last year introducing a new scheme, the long-term solution of boosting domestic savings will take time.

And although privatization has powered ahead, observers point to the absence of large foreign investors, for example in the recent sales of energy distribution companies. Total FDI last year was around $12 billion with $15-to-$20 billion expected this year. This figure is relatively low, given Turkey’s size and potential. Observers say it reflects concerns about Turkey’s inflexible labor market, as well as its education system: Turkey lacks graduates with decent scientific and technical qualifications or adequate foreign linguistic skills. There are also concerns about the tax system, which, despite tinkering, remains complex and opaque. All these problems will take time to fix, and that’s assuming the authorities recognize what needs to be done if Turkey is to reach its full potential.

However, Turkish officials are confident that once the global economy recovers and the picture within Europe improves, Turkey’s appeal as an FDI destination will grow. According to Ispat’s Ayci, the most attractive sectors will be energy (including renewables), chemicals, real estate, finance, information and communications technology, automotives, machinery and agriculture. He says authorities have moved decisively to improve the investment environment over the past 10 years—starting with the introduction of the 2003 Foreign Investment Law, which guarantees a level playing field for foreign and local investors. Corporate income tax is down to 20% from 33% a decade ago, and setting up a new business takes six days against the one month that was typical before the AKP came to power.

“Turkey has created more than 3.5 million new jobs since the onset of the global financial crisis in 2009,” notes Ayci. “This makes Turkey one of the largest employment-generating countries in the world.” And one of the more confident. On March 24, president Abdullah Gul welcomed the International Olympic Committee as Istanbul burnished its credentials to host the 2020 Olympic Games, competing against Madrid and Tokyo. “This is the time for Turkey,” he declared.

It certainly seems to be the time for its economy and banking sector. “Per capita national income increased by 2.5 times and exceeded $10,000 over the last ten years in Turkey and is projected to…reach $25,000 in 2023,” says Odeabank’s Ozkaya. “This says everything regarding Turkey’s potential.”

MOUNTING GROWTH AMBITIONS MADE MANIFEST IN BORSA ISTANBUL

By Valentina Pasquali

With above average growth, rising domestic consumption, thriving trade relations across the Middle East and a high-performing banking sector, Turkey is an economic powerhouse in the making. Its mounting ambitions are reflected, among other things, in the launch in April of the new $326 billion Borsa Istanbul.

This revamped stock exchange was born out of the merger of the Istanbul Stock Exchange, the Istanbul Gold Exchange and the Futures and Options Exchange, which had previously been headquartered in the western city of Izmir. It is part of a larger effort by the Turkish government to turn Istanbul into a prime financial center for the region and possibly the world. The plan also calls for the gradual relocation, from the capital Ankara to Istanbul, of major public banks, the Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency, the Capital Markets Board and the Central Bank.

While observers generally praise this initiative, they warn that Turkey has much left to do if it wants to compete with other emerging financial hubs, such as Dubai. “Many commentators have noted that the new law was put into effect hastily, is not transparent, and has the danger of giving arbitrary powers of control to the Capital Markets Board (CMB) over publicly traded companies,” notes Sumru Altug, economics professor at Koç University in Istanbul.

“As long as the tax system remains convoluted, Istanbul traffic congested, the English proficiency of the labor force low, regulatory environment unpredictable, and rule of law sketchy, Istanbul doesn’t really stand a chance of becoming a financial center,” adds Naz Masraff, the London-based Turkey analyst for Eurasia Group. “You need more than a tulip rebranded bourse to actually become ‘worth investing’ in.”

The biggest problem Borsa Istanbul faces right now is the lack of foreign stocks traded there. Only one out of 332 listed companies is non-Turkish (though it is a catering partner to Turkish Airlines). To address this flaw, authorities have launched an outreach campaign, “ListingIstanbul”, to attract listings from countries around the world. So far, they have signed partnership agreements with eight brokerage firms in Asia, Africa and the Caucasus, which are tasked with the recruiting effort.

At the end of the day, international competition will make or break Turkey’s aspirations, with a similarly aggressive bid coming, for example, out of Moscow in Russia. “Istanbul is not the only city hoping to become a financial center,” says Emre Deliveli, a Turkish economist, commentator, and independent consultant. According to him, if Turkey wants to succeed, it might need to make its intentions clearer. “They seem undecided on whether they want to be a regional financial center catered to the Islamic world, an Eastern European hub, or are trying to compete with the likes of Singapore.”

While global ascendancy seems out of reach for the time being, Istanbul might have a market-specific shot at the regional level. “The notion of developing Istanbul as a direct competitor of places such as London, Frankfurt, Hong Kong, Moscow or even Dubai does not seem realistic,” says Altug. “Where Turkey may have an advantage is in terms of creating a new center for Islamic finance.”