Strong growth and other upbeat data in 2015 bucked the West’s collective vision of a nation in crisis. But without structural reforms, the picture may darken.

Barely a day passes when Turks don’t wake up to another grim headline suggesting they are facing an existential crisis. With Ankara now fighting several major terrorist groups—Daesh (ISIL), the Kurdistan Worker’s Party, or PKK, and the far-left Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party-Front (DHKP-C)—deadly suicide attacks and bombings have become depressingly frequent, with the March attacks in central Istanbul and Ankara making news around the world. Southeastern Turkey has become increasingly militarized, with the war in neighboring Syria complicating the military’s actions against the PKK, with whom Turkey’s president Recep Tayyip Erdoan has ruled out any negotiations. The refugee crisis continues, with Turkey now home to 2.5 million refugees, putting a major strain on resources and, in some places, social cohesion.

If that weren’t enough, in early April, Turkey faced the prospect of yet another conflict on its borders, this one between its firm ally Azerbaijan and Russia’s ally Armenia, over the breakaway region of Nagorno-Karabakh, an Armenian enclave within Azerbaijan occupied by the latter since the early 1990s. The fighting threatens to further poison relations between Turkey and Russia, which are at their worst in decades since Turkey shot down a Russian jet in November for straying into its airspace. Russia has imposed economic sanctions on Turkey, which are expected to impact severely on tourism but also on exports of agricultural and manufactured products.

“Turkey today is unpredictable, polarized and volatile, with its economy in the midst of long-term stagnation,” says Fadi Hakura, Turkey analyst at Chatham House. He puts the blame firmly on Erdoan’s increasingly authoritarian and interventionist tendencies. “Foreign policy is undermining trade and economic policy and making the country increasingly isolated.”

Hakura says the collapse in relations with Moscow has cost Turkey some $12 billion in lost trade there, while bilateral trade with Iran has more than halved since 2012, to $9.7 billion last year despite the two countries’ having signed a preferential trade agreement cutting tariffs on hundreds of products. Trade with the Gulf States has also fallen, from almost $13 billion in 2013 to below $9 billion last year.

“Erdoan’s policies are not improving or sustaining the confidence that is vital to Turkey’s long-term future,” Hakura says. “The government would need to perform a 180-degree turn before the outlook improves.”

Yet many statistics paint a rather different picture.

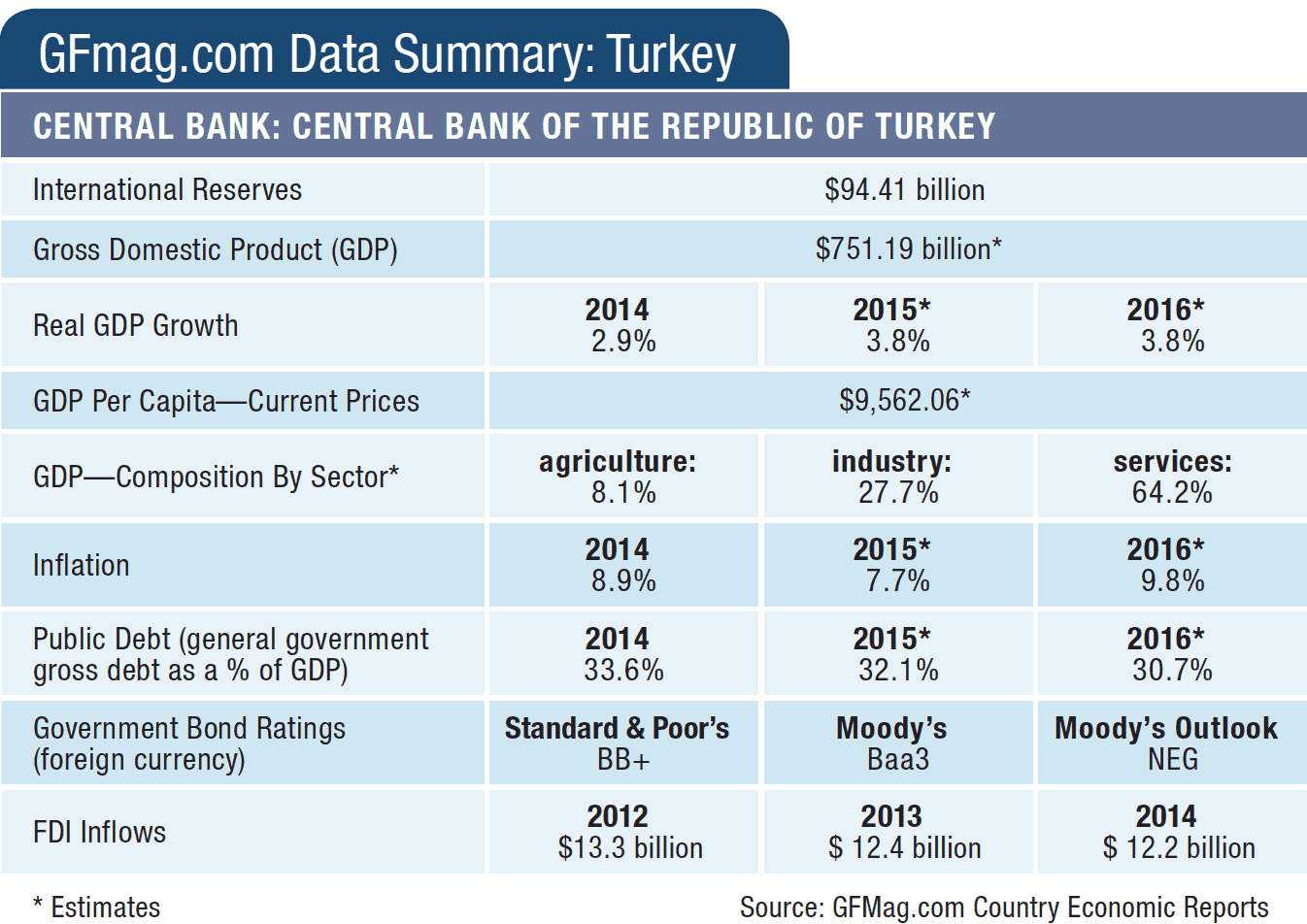

When final quarter GDP figures for 2015 were released, showing growth of 5.7%, there was a collective gasp among analysts: Not only was this well above their consensus of around 4.5% but it was the highest since 2011, boosted by a rise in net trade, as exports rose and imports dropped, reflecting low global energy prices. GDP grew 4% over the year, compared to 2.9% in 2014, with the World Bank forecasting 3.5% for both 2016 and 2017.

Other figures appear equally encouraging. Industrial production in February rose 5.8% against consensus forecasts of 4.5%, suggesting the weaker lira is helping export demand.

And according to Fitch, the central government debt as a proportion of GDP dropped to 32.6%—some 10% below the peer median average, while the central government deficit last year was slightly down, at just 1.2% of GDP. Perennial concerns about Turkey’s large external obligations—some 38.4% of GDP—have been eased by changes in which banks are helping finance them, using loans with longer maturities.

Even inflation—an ongoing concern in Turkey—appears benign right now, at just 7.5% in March, reflecting lower food and energy prices (although underlying inflationary pressures remain strong).

And those saying confidence is absent from Turkey right now should take a look at the figures released by international realtor agency Knight Frank in March, which show that property prices rose faster here than anywhere else in the world: 18.9%, compared with the global average of 2.7%.

So just what is going on?

“Lower commodity prices—particularly energy prices—have been a huge bonus for Turkey, benefiting real incomes and the current-account deficit. They have helped external imbalances, which are one of the key weaknesses of the Turkish economy,” argues Paul Gamble, head of emerging Europe sovereigns at the Fitch Ratings.

Roxana Hulea, Turkey analyst for Societe Generale, explains 2015’s fourth-quarter performance as pent-up demand finally forcing its way through, supported by low energy prices and the lira’s relative strength, while high property prices reflect rising demographic trends. She suspects the growth momentum will not last.

SLOWDOWN EXPECTED

“I think figures for the next quarters will show a slowing down, reflecting more-depressed consumer confidence because of the growing security concerns,” she says.

This would be negative, because domestic demand and public investment are currently supporting Turkey’s economy. Last year saw a slump in FDI to around $15 billion, well down from pre-global-crisis levels of more than $20 billion and fairly poor, given Turkey’s size and potential. Turkey is down in almost all indicators in such surveys as the World Bank’s Doing Business (where it slumped four places, to 55 out of 189 countries in the rankings) and the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report, where it dropped six places, to 51.

“The reality is that structural reform has been at a standstill during the AKP’s [the ruling Justice and Development Party’s] last two parliamentary terms. Labor market reforms and support for private investment are needed to help shift towards a growth model led by the private sector,” she says.

Bulent Sengonul, head of research at Investment in Istanbul, agrees that evidence of a slowdown will soon become apparent. “Private investment has been the weakest link of growth for the last four years,” he says. “Unless we see a clear structural reform roadmap, we do not expect a strong revival in investment appetite in 2016,” he adds, noting that ongoing geopolitical tension and rising terrorist activities “might exacerbate the deterioration in investment.”

One thing Erdogan could do is ease the tense political environment that he continues to preside over even after the AKP won an unexpected majority in last year’s second general elections, on November 1. Critics charge that he is still seeking to bring about a referendum to shift Turkey toward a presidential system that would give him untrammelled power similar to what president Putin has in Russia.

The focus in the short term will be on the central bank, where Murat Cetinkaya, formerly deputy governor, was appointed to replace Erdem Basci as governor when the latter’s term ended on April 19. A bank insider and previously also a board member of Halkbank as well as deputy director at the Islamic bank Kuveyt Turk, Cetinkaya is seen as safe pair of hands.

The big question is whether the new governor and the bank’s MPC (Monetary Policy Committee) will remain market-friendly–as many in the government prefer—and resist the interventionist policies favored by the president and much of his team, who many believe urged the unexpected 25-basis-point cut in the marginal funding rate in March.

“There are legitimate reasons to worry that interest rates will be pushed down further, not only … to support growth but also owing to president Erdoan’s now well-known, doctrinaire aversion to high rates. If and when things worsen for emerging markets, Turkey may be punished more harshly if rate cuts are not justified by the inflation trajectory,” argues Inan Demir, chief economist at Finansbank in Istanbul.

Paul Gamble of Fitch, which maintained a BBB- stable outlook on Turkey in its February review, says policies rather than personalities matter. The last two years were defined by a succession of polls, which complicated the environment for structural reform. He says that over 2016, it will be important to keep a close watch on fiscal policy: There are several uncertainties here, including the amounts spent on the military, on looking after the country’s 2.5 million migrant population and on meeting its obligations on the implementation of the recent 30% hike in the minimum wage (the government has promised businesses it will meet 40% of the cost of this over 2016). He suggests, however, that Ankara now has a great opportunity to reenergize its structural reform program.

“The government’s policy agenda has all the components that would help Turkey resolve its many economic imbalances; the big question is over implementation,” he says, adding that Turkey would benefit from moving swiftly toward a more-balanced growth model characterized by more private investment.

Roxana Hulea of SocGen agrees.

“There’s a saying, ‘Make hay while the sun shines.’ Turkey really needs to start undertaking reforms and putting its house in order before global economic and business conditions change for the worse.”