New political party’s moves to roll back market initiatives may damage Poland’s relatively strong economy.

When Andrzej Duda of the conservative Law and Justice Party was elected Poland’s president last year, it was clear that his populist platform had struck a chord with voters. Still, many worry that the cost of such populist proposals will be too high—despite Poland’s strong economy.

“Law and Justice wants more self-determination and more emphasis on Poland,” says Lucja Cannon, a former economic adviser to the Polish government and to several East European governments. “The ruling party isn’t against the direction of the economy. It just wants more political control of that direction.”

After Law and Justice finally took charge of the government in November, it made clear that it would assert greater political control over the economy. Its reforms haven’t had full impact yet. But Leszek Balcerowicz, one of Poland’s most influential economists, thinks the effects are already beginning to be felt.

“The economic policy proposed by Law and Justice and partly implemented is already weakening what is in need of repair, namely public finances,” says Balcerowicz, one of the architects of the post-Berlin-Wall Polish economy and now professor of economics at the Warsaw School of Economics. “The policy also weakens what has been strong until now, specifically the banking sector, and it weakens that which requires strengthening by reforms, namely the forces driving long-term growth of the economy.”

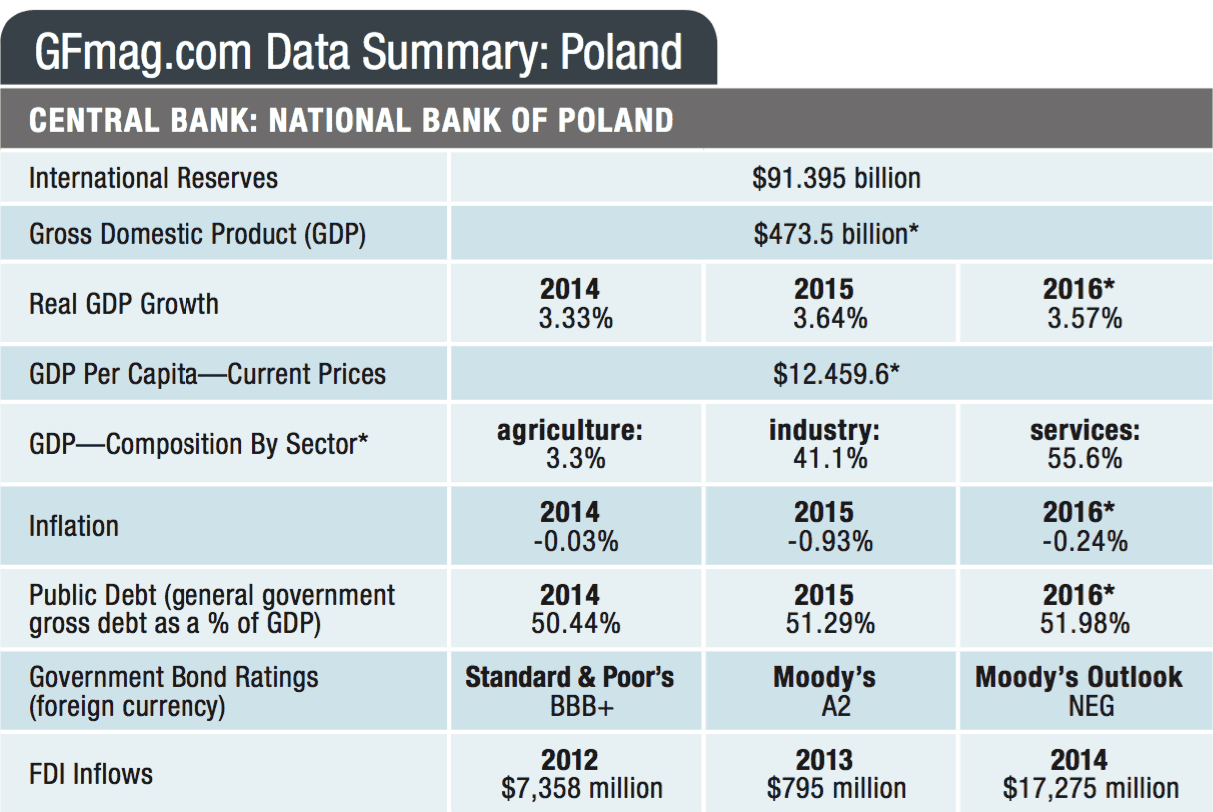

For all the criticism of Law and Justice, the current macroeconomic situation of Poland continues to look promising, with estimated GDP growth for 2016 at 3.7%, unemployment below 10% (low for Europe), little deflation, a projected budgetary deficit at 2.7% of GDP (below the 3% requirement), and public debt at 52% of GDP. The forecast for 2017 is not bad either—the budgetary deficit is expected to be larger, but still below 3%.

Law and Justice has made no bones about where it stands. It believes that economic policy needs to favor small businesses and families, and that foreign companies, especially banks, have had too much influence over the direction of Polish development. For many, the party’s proposals raise fears of excessive state intervention and control; political intervention and control are still grim reminders of the Soviets and the communist past.

Mateusz Morawiecki, deputy prime minister and minister of sustainable development, says the time has come for change. “A free market is key for development of the country, but mature states are able to skillfully support this free market by state policies,” he says. “We must skillfully defend against strong foreign monopolies and create internal sources of development.”

In January, S&P downgraded Poland’s sovereign credit rating to BBB+ and gave it a negative outlook, explaining “Poland’s system of institutional checks and balances has been eroded significantly” by the new ultraconservative government’s policies.

“The S&P downgrading of Poland will mean that some investors will hold back investments previously intended,” says Roman Rewald, a former chairman of the American Chamber of Commerce in Poland and a partner at Weil, Gotshal and Manges in Warsaw. “We will never know how much of this investment issue is related to the liquidation of OFE (Polish private retirement funds) taken over by the previous ruling party, a major factor in the party’s defeat in the last elections.”

Some foreign investors are not deterred. In May, Daimler announced it would build a €500 million ($565 million) Mercedes engine factory in Poland, part of its continuing effort to search for lower-cost manufacturing environments. The Daimler announcement follows investments in Poland made by Volkswagen, Fiat and General Motors.

Rewald is not surprised. Economic decisions often override political considerations. “For years, the world’s capital was doing business with the Polish communist government despite all the restrictions and civil rights violations and nationalization, which may slowly return to Poland under [the Law and Justice Party],” he says. “So, you may not see any outrageous reactions of business people to the changes in Poland.”

Maybe there will be fewer investments and contracts, but that will be very difficult to ascertain. “The inevitable marginalization of Poland internationally, and later downgrading the stature of its economy, will not happen overnight,” adds Rewald.

Balcerowicz, best known for the “shock therapy” policy that dramatically transformed the country from a moribund, centrally planned economy into a dynamic market economy, thinks that many of the new ruling party’s populist proposals, such as a lower retirement age, a radical increase of the income tax threshold, and free medications for senior citizens, cannot be sustained, and that the fallout will spread to the economy and dampen investor confidence.

The “500+” flagship program—a child benefit scheme which will give parents a monthly allowance of 500 Polish zlotys ($129) for every second and subsequent child up to age 18—will cost 17 billion zlotys in 2016, to be financed with extra income from the sale of telecom licenses and exceptionally high profit payments by the National Bank of Poland to the budget. In 2017 the program is expected to cost 22 billion zlotys—and the payoff is doubtful.

“No studies known to me confirm the Law and Justice propaganda that a lot more children will be born in Poland thanks to these billions. In the best case, the cost of each additional child will be one million Polish zlotys. Billions from taxpayers’ pockets will serve to gain votes of the beneficiaries of 500+,” Balcerowicz says. “Even if sectoral taxes (from banks and commercial firms—or even their clients) plus the better collection of other taxes were sufficient to cover the cost of 500+, there won’t be enough money for Law and Justice’s other promises—not unless Law and Justice increases the already vast budget deficit.”

But new loans will be more expensive, so the risk of disorder in Poland’s finances will increase. The already accumulated deficit and the risk of slower growth in the world economy require additional steps to rationalize the budget. And while that may achievable through a steep rise in taxes, it would hinder the growth of the Polish economy in the long run.