Tariff rulings linger in court, but businesses are preparing for price hikes and supply chain disruptions anyway.

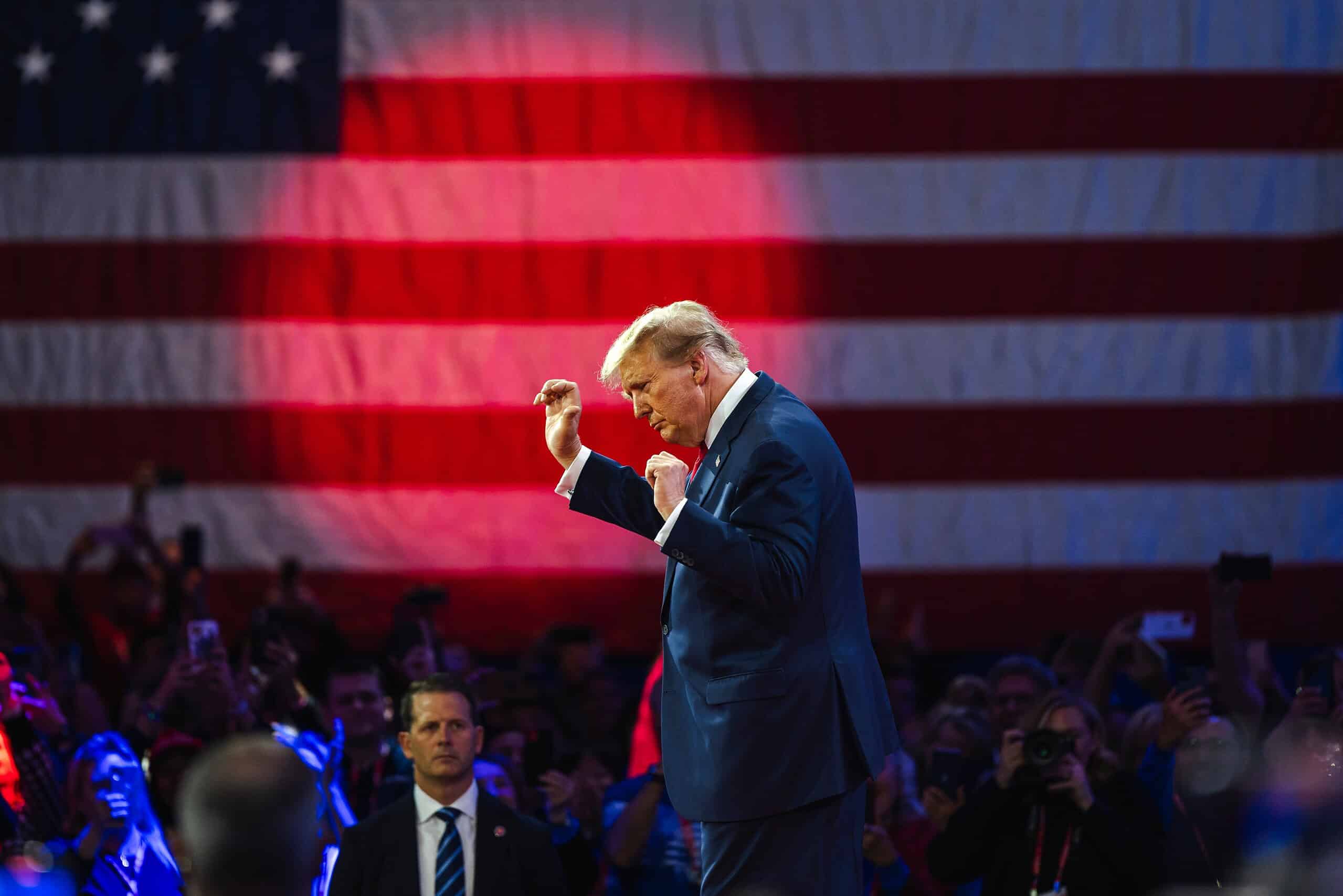

US President Donald Trump suffered a setback in the courtroom at the end of August that could shake one of the highest-profile elements of his economic agenda.

Earlier this year, Trump declared sweeping tariffs on foreign goods, claiming emergency powers that allow him to bypass Congress in the name of protecting American jobs and boosting the economy. The US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit wasn’t buying it. In a 7-4 decision, the court largely upheld a lower federal trade court ruling that Trump exceeded his authority in declaring national emergencies to justify tariffs on nearly every country in the world.

But the ruling doesn’t kick in just yet. The court has delayed issuing its mandate until October 14, giving the government time to appeal to the US Supreme Court. If the Supreme Court takes up the case, the legal battle could stretch well into next year, prolonging uncertainty for corporates across the globe.

For companies, the question isn’t just whether Trump’s tariffs are legal. It’s whether they can afford to ignore them.

Companies in sectors ranging from luxury to auto to consumer goods are adjusting pricing, sourcing, and supply strategies to navigate a landscape in flux. The takeaway for businesses is clear: The battle over tariffs isn’t just legal, but economic, and the stakes are high for both profits and consumer prices.

“Get On With It”

“I don’t think the recent federal appeals court case registers with most businesses at this point,” says Olu Sonola, head of US Economic Research at Fitch Ratings. “They are basically just trying to get on with it. They know the Trump administration will look for other ways to impose the tariffs if the Supreme Court eventually overturns the lower-court decision. Most businesses are reacting to what’s in front of them, rather than hoping for relief.”

Even a court victory, in other words, doesn’t mean the fight is over for companies that rely on imported goods. From electronics to consumer products to heavy machinery, businesses are now motivated to take new approaches to sourcing, change supply chain strategies, and in most cases, pass the costs on to consumers.

In electronics and gaming, the effect is clear. Sony, Nintendo, and Microsoft have each raised prices on their consoles and games to offset new import costs. Household and consumer goods makers—Procter & Gamble, Hershey, Conagra Brands— are either adjusting product prices or turning to alternative sourcing methods. Retailers like Walmart and Home Depot, two companies that base their business model on offering affordable options for the average shopper, anticipate further price increases across multiple categories for the rest of the year.

And these aren’t the only companies wrestling with tariffs: far from it.

A survey conducted in May by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York found that roughly 75% of firms—both manufacturing and service—have passed at least some tariff-related costs on to customers. Gartner reports that nearly 45% of supply chain leaders plan to shift new tariff-related costs “fully or nearly fully” to customers.

“We are not seeing importers reduce the prices of goods coming into the US,” Sonola says.

Manufacturers are particularly vulnerable, including companies based in Europe, that have a global presence.

London-based CNH Industrial depends on imported steel, aluminum, and specialized machinery. CFO Jim Nickolas warned in a second-quarter financial report that while impacts during that period were modest, more significant effects were expected in the second half of 2025.

“It’s a new element of the business that wasn’t there 12 months ago,” Nickolas tells Global Finance. “We have large teams of people trying to understand it and mitigate the effects of the tariffs. In the short run, there are headwinds, no question. You do what you can to offset it.”

CNH’s US-based rival, Deere & Co., projects that tariffs could cost the company $600 million by year-end. A Deere spokesperson declined to comment.

European luxury brands are leveraging pricing power to offset the new duties. Paris-based Kering, which counts Gucci, Yves Saint Laurent, and Balenciaga among its portfolio brands, announced in July global price increases and the possibility of further hikes in the autumn. Hermès raised US prices in May, while LVMH has steadily increased prices to protect profit margins.

“Tariffs are delaying some sourcing decisions, maybe some footprint manufacturing decisions,” Nickolas observes. “We really don’t know until the policy stops moving, and we know it’s still moving.”

For many businesses, the uncertainty is as costly as the tariffs themselves.

CNH is taking what Nikolas calls “tactical actions.” For example, the company, which sells agricultural machinery and construction equipment, is pausing shipments from its India operations into the US. Why? “Because a 50% tariff rate makes those products uncompetitive.”

The Trump administration recently doubled tariffs on Indian imports to 50% as a punishment for Indian purchases of Russian oil.

That’s not to say CNH is exiting India. “We think India is an excellent growth market for us,” Nickolas says. “But tactically, in the short run, until we have certainty, we’re pausing shipments from India to the US.” CNH is also looking at minimizing shipments from Brazil, which was also hit with a 50% tariff, to the US.

Bad Signs, Good Omens

The automotive sector illustrates the dual pressures of tariffs and inflation. Duties on imported cars and parts have driven vehicle costs up by as much as $6,000 in some cases. General Motors is absorbing more than $1 billion in tariff costs rather than pass them on to consumers, but projections suggest prices may still rise. Japanese-assembled models could see a 9% increase, Mexican-assembled vehicles about 10%.

“The automotive sector is one that I will certainly keep an eye on,” Sonola says. “Imports of autos, parts, and other transport equipment have declined by almost 20% compared to 2024 levels, while the effective tariff rate on these goods is now about 18% and rising. This will amount to about $60 billion in added costs the industry has to grapple with. The 15% cap on autos and parts announced in the deal with Japan may be a good omen going forward, but uncertainty remains.”

Volkswagen CEO Oliver Blume says US tariffs have cost the company “several billion euros” in 2025 alone. Across Europe, auto manufacturers are bracing for the impact of 15% tariffs on many goods exported to the US, which could mean higher prices for American consumers.

The retail sector is another frontline of the tariff battle. Clothing, footwear, toys, and games imported from China, Vietnam, and Bangladesh are seeing levies from 15% up to 145%.

Adidas, the German sportswear brand, warned that US tariffs would cost it an additional €200 million ($231 million) in 2025 and confirmed plans to raise prices for US consumers.

“While we are facing direct and indirect impact from tariffs, we have been actively offsetting the impact through flexible sourcing, disciplined buying closer to market, and selective pricing adjustments that maintain our value proposition,” says CEO Bjorn Gulden. “The challenge is predicting whether these tariffs could trigger major inflation in the US market.”

Economists note that while tariffs aren’t inflationary in the monetary sense, they do increase the cost of goods and raw materials.

“Strictly speaking, tariffs are not inflationary as inflation is a monetary phenomenon,” says Phillip Magness, senior fellow at the libertarian Independent Institute. “But they do result in price increases on specific goods and raise costs on many raw material inputs.”

Harvard Pricing Lab data show that prices at major US retailers rose between April and August, a pattern likely to continue if tariff pressures persist. August’s Consumer Price Index showed a 2.9% year-over-year increase, the fastest since January, as Trump’s import duties filtered through the economy.

For now, companies are trying to absorb some costs while preparing to pass others along to consumers.

“In the short term, some companies may try to absorb the dual hits of inflation and tariffs by keeping prices low as a strategy to retain consumers,” Magness notes. “Beyond that time horizon, the situation becomes more difficult to sustain, and we will see price increases passing through onto consumers.”

Until the Supreme Court rules, or the administration revises its policies, businesses are operating in a state of constant recalibration. As Nickolas puts it, “You would like to say, just, ‘Okay, where is this going to end?’ So, then I can really plan.”