World trade growth is slowing. Its future may depend on internal trade within a handful of discrete, powerful regions—especially Asia.

Thirty years ago, the idea that the cars we drive might include components from dozens of countries, or that one in seven people on the planet would belong to an invisible social network, would have been fanciful. Yet today, few nonagricultural products are manufactured and assembled in a single country, and the world has become ever more electronically and culturally connected. Underlying these phenomena is the huge growth of global trade, especially since the 1990s. Taken together, these trends have become known as globalization.

Globalization has long appeared unstoppable. The world’s politics have shifted dramatically from the bipolar tension of the Cold War to a more commerce-focused multilateralism. The recent conclusion of the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade deal and the eventual likely passage of its transatlantic counterpart appear to indicate that globalization still has momentum. The online dominance of a small handful of firms like Google further reinforces the modern world’s apparently borderless nature.

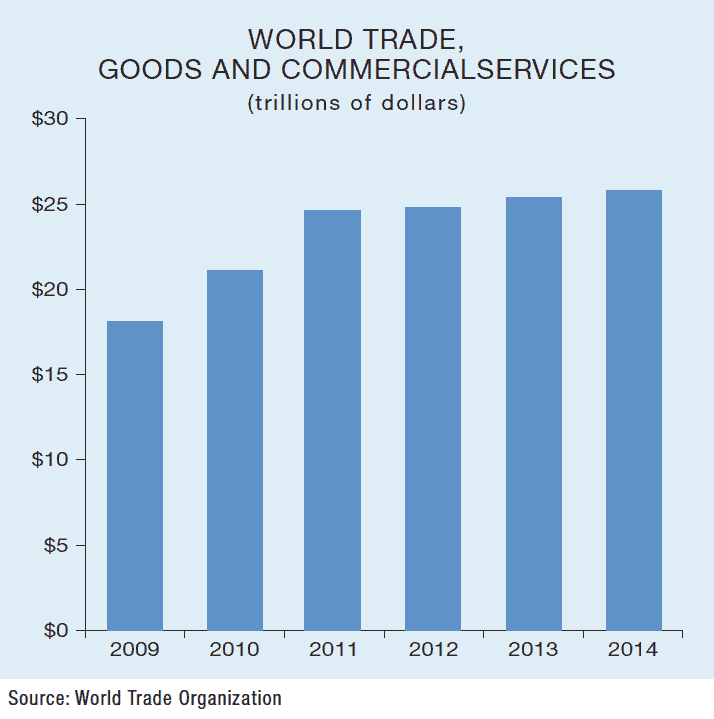

Yet beneath globalization’s seemingly inexorable advance are signs that its engine—trade—is stalling. Since the financial crisis, trade growth has slowed significantly. The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) expects world trade growth for 2015 to come in at just 2%, compared with 3.4% in 2014. (By contrast, according to ING research, annual trade growth between 1961 and 2013 averaged 10%.) The slowdown puts globalization at risk and could significantly affect world economic growth.

Presenting the OECD’s most recent economic outlook in Paris in November, secretary-general José Ángel Gurría called the deceleration of global trade “deeply concerning,” because “robust trade and investment and stronger global growth should go hand in hand.” The G20 leaders echoed this view one week later in their communiqué following the Antalya Summit, which reaffirmed their “strong commitment to better coordinate our efforts to reinforce trade.”

Global trade is not simply a by-product of growth, according to Raoul Leering, head of international trade research at ING and author of The World Trade Comeback, published last April. “It can be an independent source of growth with positive effects on the standard of living,” he explains. He cites 2011 research by Joachim Wagner, an economics professor at the University of Lüneburg in Germany, showing that exporters are more productive than domestically focused companies. The same research showed that companies entering a foreign market increase overall productivity in their industry.

The symbiotic relationship between trade and economic growth became supercharged in the 1990s. During the 15 years leading up to the financial crisis, according to ING data, world trade grew 1.9 times faster than world GDP. Between 1970 and 2013, the ratio was 1.7. However, from 2008 through the present, it has hovered around 1. If the link between trade and growth is weakening, both may suffer.

PROTECTIONIST BARRIERS

Many factors have contributed to the slowdown in trade growth. For one thing, the 1990s and 2000s provided an unrepeatable backdrop for accelerating world commerce. The end of the Cold War in 1991 facilitated the integration of the former Soviet Union into the global economy. Even more important, China joined the World Trade Organization—and by 2012 had overtaken the US as the number-one trading nation. These immense geopolitical changes extended companies’ supply chains globally and hugely increased trade.

However, even taking these one-off shifts into account, trade growth since the financial crisis has been moribund. A rising US dollar, falling commodity prices and the retrenchment of supply chains involving China have all played a part. But in a recent report for the Center for Economic Policy Research, Simon Evenett and Johannes Fritz say these factors “place too much weight on the volume of global exports” and ignore, among other facts, that trade declines have been concentrated in a small number of product categories, such as manufactured goods.

Evenett and Fritz argue that protectionism is gaining ground and hindering global trade. Their report, The Tide Turns? Trade, Protectionism, and Slowing Global Growth, highlights 539 government-imposed trade distortions in the first 10 months of 2015—443 of which were put in place by G20 countries. The measures harmed foreign traders, investors, workers and owners of intellectual property. “In no previous year have we found so many trade distortions so quickly,” says Evenett. “Bearing in mind that our initial totals have tended to be revised up substantially over time, finding so many trade distortions is troubling.”

Since the financial crisis erupted, G20 governments have imposed 3,581 measures that harmed foreign commercial interests, according to Evenett and Fritz. Of these, 81% remain in force, undercutting claims that crisis-era protectionist measures were only temporary. It seems that trade is under attack.

According to a recent report by Credit Suisse entitled The End of Globalization or a More Multipolar World?, declining trade growth is one of several factors that could cause globalization to decelerate. “Globalization has been the most powerful economic force of the past 20 years,” says Michael O‘Sullivan, chief investment officer for the UK & EEMEA, private banking and wealth management, at Credit Suisse. “But its continuation is not a given.”

Credit Suisse’s report outlines three scenarios: (1) globalization thrives; (2) a multipolar world emerges; or (3) globalization comes to an end. Under the first scenario, the dollar remains paramount, Western multinationals dominate business, and “the fabric of international law and institutions [are] still Western in nature.” In the second scenario, Asia continues to ascend economically, creating a multipolar world and global institutions that reflect the new power balance. Regional financial centers and region-dominating corporations would rise in importance, and “managed democracies” would become more common, along with competing, regional regulatory regimes. The third scenario is the end of globalization.

Which of these is most likely? Many factors that undermine globalization, according to Credit Suisse—such as slowing trade and economic growth, a rise in protectionism, currency wars and clashes between the great powers—are clearly more prominent than they were a decade ago. For example, geopolitical tensions were elevated significantly by Russia’s intervention in Syria. However, the world seems to be some way from the sort of shock that might presage an end to globalization. That leaves two other possibilities.

“In no previous year have we found so many trade distortions so quickly . . . [and] our initial totals have tended to be revised up.

Simon Evenett, Center for Economic Policy Research

“MULTIPOLAR STATE”

Credit Suisse does not stipulate minimum trade growth levels for its “globalization thrives” scenario. However, it seems doubtful that the pre-crisis growth rates will return. ING’s Leering says that, based on earlier recovery cycles in the world economy, the ratio of global trade growth to world GDP growth will rise modestly to 1.2 by the end of 2016. Subsequently, he believes, implementation of the 2013 Bali Package, which will reduce import tariffs and streamline customs procedures, will result in net offshoring of production and lift the trade-to-GNP growth ratio to 1.5.

Yet that trend is far from guaranteed and could easily be stopped in its tracks by an economic slowdown or by any of Credit Suisse’s globalization-killers, including high levels of sovereign debt. More likely, the relationship between trade and economic growth will weaken somewhat over the medium term—though it certainly will not break down—as the exceptional gains in trade from ever-longer global supply chains made in recent decades become harder to replicate. At the same time, the nature of globalization looks set to change. Credit Suisse concludes that “the world is currently in a benign transition from full globalization to a multipolar state, though this is not complete.”

Recent trade agreements and their expected impact on future trade growth bear out this analysis. Although the recent TPP has been heralded as a fillip for global trade, it will actually do more to spur regional trade. TPP and its counterpart, the Transatlantic Trade and Investment Partnership, came about precisely because the Doha Round of WTO talks have failed to achieve anything significant since 2001. To date, only the Bali Package has emerged.

Meanwhile, even optimistic trade observers acknowledge that trade patterns will change in the coming years. An HSBC report called Trade Winds, published in November, suggests we are on the verge of a decade of global trade growth and forecasts that worldwide exports will quadruple to an estimated $68.5 trillion by 2050. The report’s authors expect this growth to be driven by a burst of intra-Asian trade that will lift the region’s share of global exports to 27% by 2050 from 17% at present. “Asia’s position at the leading edge of technological and supply chain innovation gives it a unique opportunity to benefit from this next wave of globalization,” says Paul Skelton, HSBC’s regional head of commercial banking in Asia-Pacific.

THE IPHONE EFFECT

No one expects the world to revert to pre–Cold War status. People around the globe today have more in common than they did in the past. Overseas travel and tourism, especially in emerging markets such as China, are growing rapidly and helping to broaden citizens’ experience of and perspective on the world. And trade, in both goods and services, has paved the way for shared global enthusiasms, from the popularity of Château Lafite Rothschild among China’s elite to intercontinental excitement at the premiere of the latest Star Wars film or new iPhone model.

Yet global trade and globalization are subject to thousands of variables, any one of which could change the way people, businesses, countries and markets interact around the world. Therefore all predictions must be treated cautiously. Moreover, trade itself is changing. As the TPP agreement acknowledges, much future trade growth is likely to come from services such as healthcare and education—facilitated by improved information technology and communications—rather than from goods. Already, services account for four out of five US jobs and a growing share of jobs in other TPP countries, according to the White House’s Office of the US Trade Representative.

It seems unlikely that trade growth will again match the heady pace it reached from the 1990s to the 2000s. Nevertheless, trade and globalization will in coming years affect more people and companies than ever before. Whether or not trade patterns, regulations and even the rule of law become more regionalized, individuals, companies and countries will continue to grow closer, not more distant. Given the huge benefits that trade and globalization have delivered for humanity so far, including lifting hundreds of millions of people out of poverty, their perseverance can only be welcome.