AFRICA 2014 | INFRASTRUCTURE

From power plants and mining to tourism and railroads, new infrastructure projects are stimulating the growth of industries across sub-Saharan Africa.

Nigerian entrepreneurs are investing heavily in a range of infrastructure projects, from power plants to water treatment plants, that are widening the base of Africa’s largest economy. Last year alone, Nigeria’s economy grew by 89%. In renewable energy, Nigeria plans to install enough power plants to generate four to 10 gigawatts of electricity, which is roughly on a par with renewable energy development in China over the past five years.

“This is the new China,” says Jesper Oehlenschlaeger, chairman of Apfoss Group, an engineering company in Switzerland that is a consultant on the $300 million JBS WindPower plant, which is designed to generate 100 megawatts of electricity in Nigeria when construction is completed in 2016. “Thousands of megawatts are needed in installed capacity within the next few years. Investments and improvements will be crucial within all areas—telecoms, transportation, water supply and so on.”

Bankers and consultants who are involved in financing and providing technical advice for infrastructure projects across Africa describe the West African OPEC-member country as an example for the whole continent to follow in the sorely needed expansion of its overstretched infrastructure. Several countries in central and eastern Africa are already following Nigeria’s example with an ambitious regional cooperation effort to develop roads and other infrastructure projects that, according to Boston Consulting Group, will stimulate the growth of least four industries in addition to manufacturing—mining, agriculture, fisheries and tourism.

“Some countries are taking the right steps,” says Ravi Suri, regional head of corporate finance at Standard Chartered Bank in Dubai. “For Africa to reach its infrastructure development goals, it is imperative that this momentum not only continue but accelerate and spread.

HOW TO FINANCE IT?

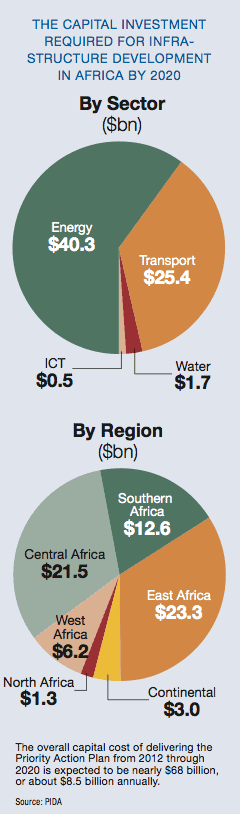

Sub-Saharan African economies are expected to grow by an average of 5.2% this year, according to the World Bank. And the Programme for Infrastructure Development in Africa (PIDA) estimates that the continent as a whole needs $68 billion of investments by 2020 to raise that annual growth rate to 6% by that time—including $40.3 billion in energy, $25.4 billion in transportation, $500 million in telecoms and $1.7 billion in water management.

The challenge is that private-sector corporations and financial institutions “don’t want to take construction risk” in Africa, while African governments lack the funds to guarantee capital-intensive projects, explains Jonathan Cawood, a partner at PwC in South Africa. “But once the rail line is built or the power station is up and running, they’re quite happy to come in,” says Cawood.

To break this deadlock, some projects have secured the backing of the export-import banks of foreign governments, particularly those projects built by Chinese state enterprises. Now some banks are tapping new sources of capital—like the diaspora of African expatriates worldwide, who remitted about $60 billion to African countries in 2012. In August the African Development Bank in Tunis announced plans to launch the Africa50 fund to finance infrastructure projects with $3 billion in seed capital plus $7 billion from the diaspora and other sources.

A blog late last year by Amadou Sy, senior fellow in the Africa Growth Initiative at public policy center the Brookings Institution, discussed such finance avenues for African infrastructure: “Diaspora bonds, like those issued by Ethiopia, as well as the placement of infrastructure bonds to the diaspora, like those in Kenya, are being explored by other African countries.” He highlighted Kenya’s marketing of infrastructure bonds to retail investors as a possible avenue for funding, along with the use of Islamic financial instruments such as sukuk, which have been used to finance infrastructure projects in Malaysia, Indonesia and the Middle East. “In project finance, solutions to mitigate credit risk could involve multilateral partners,” he added.

In electrical power, which experts say is leading the development of all other infrastructure on the continent, the Nigerian government is putting in place a series of policies to help kick-start new projects. And now several other African countries—notably Cameroon, Ghana, Kenya and Uganda—appear to be following the example of the continent’s most populous nation.

Bankers at several international banks praise the governments of these countries for taking steps to “unbundle” electrical power monopolies—in effect, separating power transmission from power generation—to make them more conducive to private investment. To get banks comfortable with the relatively high political risk of doing business in Africa, the World Bank has stepped in to provide “partial risk guarantees,” which ensure investors will be paid with their share of electricity tariffs if the host government fails to pay.

As these reforms materialize, countries are adjusting the mix of fuels used in existing power plants to meet immediate demand. For example, says Suri, “coal is used only where necessary.” In renewable energy, says Oehlenschlaeger, the authorities are prioritizing projects like solar energy plants— which can be up and running within months—over hydropower plants, which can take several years to develop.

Privatization is taking different regulatory forms in different countries, which is keeping international bankers on their toes. South Africa, the continent’s most developed nation, is allowing private investment to go through the state’s electrical power monopoly, Eskom, which started rolling “schedule blackouts” rather than unbundling, after a disruption in coal supplies.

“There is no standardized model [of privatization] across Africa,” says Theuns Ehlers, head of resource and project finance at Absa Bank’s corporate and investment banking division in Johannesburg. “Outside of South Africa, you have to start a lot of these things from scratch.”

But that doesn’t deter domestic entrepreneurs, many of whom are perfectly comfortable with the complexities of local regulations. One is Bestman Uwadia, a Nigerian entrepreneur who migrated from telecoms to wind power four years ago, rallying Nigerian investors and hiring Apfoss to structure the JBS deal. “Nigeria is a very rich country,” says Oehlenschlaeger. “A lot of local Nigerians are willing and able to participate.”

“There is no standardized model {of privatization} across Africa. Outside of South Africa, you have to start a lot of these things from scratch.” ~ Theuns Ehlers, Absa Bank

International banks are paying attention, and they are giving South African bankers, who once considered themselves to have a higher risk appetite than their American and European peers, a run for their money.

“In [the] last six months, we have seen more competition coming to market, especially on African projects,” says Rentia van Tonder, head of power, infrastructure and renewables at Standard Bank in Johannesburg. “You are finding more-lucrative and –bankable projects.”

CENTRAL CORRIDOR DRIVES DEVELOPMENT

In other infrastructure sectors, the path of progress is being carved from east to west by the Central Corridor, a network of highways that connects seaports in Tanzania to the landlocked nations of Burundi, Rwanda, Uganda and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Regulated by the Central Corridor Transit Transport Facilitation Agency (TTFA), which is run by all five countries, this regional cooperation effort is funded mainly by traffic from the mining and petroleum industries but is intended to promote so-called secondary industries en route, including agriculture, fisheries and tourism.

In agriculture, for example, the TTFA’s priority is cotton, coffee, tea, sugar and rice, which are often exported in raw form to Western countries where the cotton is spun into yarn, the coffee beans are roasted and ground, and the other so-called soft commodities are processed. But with the right infrastructure in place, Oehlenschlaeger explains, much of the processing could just as easily be done locally to serve domestic markets, keeping the added value on African soil.

In fisheries the Nile perch industry in Mwanza on Lake Victoria, a mesoscale prawn culture facility in Bagamoyo on the Ruvu River estuary, and a mesoscale tilapia culture facility in the Lower Rufiji Basin are the priorities.

As for tourism, the TTFA plans to improve railroad links between the five countries concerned in order to move leisure travelers around the region. Attractions include gorilla trekking in Rwanda, chimpanzee trekking in Tanzania and scenic nature walks around lakes in Rwanda, Burundi and Tanzania. The TTFA is also touting the development of new resorts and conference centers around Dar es Salaam, Tanzania’s largest city, and Zanzibar, an autonomous region of Tanzania.

“Infrastructure is really viewed as the requirement to get all of these industries not only dependent on one another but also independent,” explains Benji Coetzee, a consultant at Boston Consulting Group in Geneva. “The [five] governments are actively participating in the development of entrepreneurs and the smaller business community along the corridor, not only to ensure that there is traffic but also to develop industries other than the resource and energy industries.”

Infrastructure investment and development in Nigeria and eastern and western African countries has provided a template for others to follow. Other African countries are drawing up plans to attract investment for new infrastructure to help stimulate business and economic growth.