COVER STORY: THE 10% + CLUB

By Laurence Neville

Predicting what countries will be the next growth outperformers is tricky at best. Those firms that back the winners will undoubtedly profit, and the countries that make the list will attract greater foreign investment and gain political clout.

Japan had it for 27 years; South Korea for more than 30 years; China for 32 years and Taiwan for an astounding 47 years. Double-digit annual growth, or something close to it, over sustained periods—has transformed nations and the global economy in the past 60 years. With growth in short supply in much of the world, discovering the formula for strong but sustainable annual economic expansion in the developing world is more important than ever.

The advent of the BRICs (Brazil, Russia, India and China) acronym by Goldman Sachs in 2001 highlighted an extraordinary advancement for these economies and—with the possible exception of Russia—they have consistently fulfilled their promise. Moreover, their economic success has been decisively leveraged into political power: Witness China’s unprecedented involvement in the eurozone’s rescue plans.

Now the search is on for emerging markets countries that have the characteristics necessary to join the elevated heights of the BRICs. For investors and multinational companies itching to spot the next opportunity, identifying likely candidates is important for future profitability. For the global economy and long-term social and political stability, the ability to nurture countries capable of strong and sustained growth is crucial.

Leading financial institutions have been keen to emulate the success of the BRIC moniker and have devised numerous new groupings of countries. Goldman Sachs invented the Next Eleven (N11), while HSBC coined the phrase CIVETS (Colombia, Indonesia, Vietnam, Egypt, Turkey and South Africa). Fidelity has focused on MINTs (Mexico, Indonesia, Nigeria and Turkey), and Citi has its Global Growth Generators, or 3G countries.

These efforts at identifying future-star economies are presumably based on more than just eagerness to create headline-grabbing acronyms. But given political and economic instability, are predictions any more accurate than crystal ball gazing? Do successful developing countries have shared characteristics? And is there any consensus about which countries will be successful in decades to come?

IGNORE THE CYCLE

For trend spotters hoping to identify the next Korea or Taiwan based on close-to-double-digit growth in 2010 or expected growth in 2011 or 2012, there is a meager harvest. According to the UN’s World Economic Outlook, published in September, only the already-mighty China, Argentina and Mongolia are on course to achieve extraordinary growth in two concurrent years from 2010 to 2012.

Argentina’s growth is expected to decline in 2012. Mongolia is on course for solid growth in 2011 and 2012, and China is expected to sustain its pace of growth across the period. Other countries have only fleeting moments when they hit the double-digit benchmark: Chad, Ethiopia, Turkey, India, Uruguay, Paraguay and the already-developed markets of Singapore and Taiwan hit it in 2010; Ghana in 2011; and Angola, Botswana, Liberia, Mauritania and Niger are expected to in 2012.

Nicholas Kwan, head of research, Asia, at Standard Chartered, says that predicting defensible growth is notoriously difficult. “It is easy to be mistaken about the sustainability of economic growth,” he notes. “Just before the Asia crisis in 1997, a World Bank study, initiated by Larry Summers, produced a report on the Asian miracle and said it would continue for many years. Months later, it fell apart.”

If near-term predictions of economic growth are unreliable, then what hope is there for DBS’s vision of Asia in 2020 and HSBC and Citi’s predictions for 2050? For David Carbon, head of economic and currency research at DBS Bank, cycles are important but structural changes are more so. “The ups and downs of the next two years will say less about where Asia stands in 2020 than the trend line that it follows for the next nine,” he explains.

SOCIOPOLITICAL STABILITY

Harvard economist Robert Barro identifies three determinants of economic growth: economic governance, which encompasses the degree of monetary stability, political rights, level of democracy, rule of law and size of government; human capital, which includes the level of education, health of the population and fertility rate; and the starting level of income per capita. Some economists would disagree with Barro’s determinants—particularly his definition of and emphasis on economic governance and the importance of political rights and democracy in influencing growth.

|

|

Ngo, BNP Paribas IP: Growth begins with strong fixed-asset investment and high savings levels |

Dong-Sinh Ngo, chief strategist, emerging markets and Asia Pacific, at BNP Paribas Investment Partners (IP), says growth always begins with a high level of fixed asset investment, which requires high levels of savings. Others say high savings rates are desirable but not essential.

What is incontrovertible is that countries need relatively stable sociopolitical environments, according to Standard Chartered’s Kwan: “Africa’s history in past decades confirms this.” Ngo agrees: “Institutions and the rule of law are necessary for growth. At the most basic level, legal institutions are needed to guarantee contracts in order to motivate people to invest.”

A sound taxation system is necessary to build wealth, and opening the economy can be transformational. “The magic of the Chinese economy was its entry to the WTO and low [trade] taxation,” says Ngo. But while Kwan cites deregulation and competition as vital to growth, Ngo dismisses market freedom as essential for growth: “Markets don’t have to be completely open to be successful—as China and Russia show.”

DEMOGRAPHIC INFLUENCE

Demographics are, by general consensus, a fundamental factor in creating growth. Karen Ward, senior global economist at HSBC, notes that demographic patterns vary significantly across the world—for example, the working population will rise by 73% in Saudi Arabia and fall by 37% in Japan by 2050—and have a major influence on growth prospects.

According to BNP Paribas IP’s Ngo, countries need a growing population with a good balance between working and nonworking people. “GDP essentially comes down to a function of productivity and population growth,” he explains. In short, as Citi’s chief economist Willem Buiter and economist Ebrahim Rahbari note in their 3G report: “For poor countries with large, young populations, growing fast should be easy.”

However, merely having the right demographic is not enough to generate growth. “A large pool of young, cheap labor is only an asset if they are productive. Otherwise it is a liability,” says Kwan at Standard Chartered. “People need to be educated at primary and secondary level for them to achieve their potential—long-term growth can’t be built on cheap labor.”

“People need to be educated at primary and secondary level for them to achieve their potential—long-term growth can’t be built on cheap labor”

—Nicholas Kwan, Standard Chartered

Ngo at BNP Paribas IP says that the track record of Singapore, South Korea and elsewhere shows that prolonged growth was fueled partly by education. “It is no coincidence that some schools in Shanghai are now ranked among the best in the world according to the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment tests,” he says.

RESOURCES, INFRASTRUCTURE AND POLITICS

Being resource-rich is not a prerequisite for growth, but it can help increase prosperity under the right circumstances. Africa provides stark evidence that natural resources can be as much of a curse as a blessing. “While Africa has them in abundance, Japan is a bare rock, Korea has few resources, and Hong Kong and Singapore have nothing but people and their geographical location,” Kwan notes. “Resources can be borrowed if necessary.”

But with sound economic governance in place, natural resources can provide the basis for sustained growth. Ngo says: “Africa represents just 4% of global GDP in US dollars. Given its low starting point and rich commodity assets, which are attractive to China, it could experience huge growth potential if the current improvements in politics and education are sustained.”

|

|

Carbon, DBS Bank: Trends over the next nine years are more important than highs and lows over the next two years |

Good infrastructure, on the other hand, is critical to forward momentum. Timothy Ash, head of emerging markets research at RBS, says: “Given the trend of demographics and urbanization, there is a basic demand for infrastructure,” he says. “Those countries that fail to meet that demand could effectively go backwards in terms of growth, given that those trends are unstoppable.”

To ensure that good infrastructure is in place to support growth, countries must have defined development strategies, says Ash. “Systems of delivery matter. Managed regimes, such as China, have proven more successful in delivering infrastructure than democracies such as India, perhaps because of the difficulty of reaching consensus. In Latin America, which has relied on market forces, delivery has been less successful still.”

But ultimately the origins of growth are political and social forces—and possibly luck in countries having the right leaders. Ngo notes: “None of the subsequent changes in China could have occurred without Deng Xiaoping, and similarly Singapore could not have become what it is today without Lee Kuan Yew. Countries can’t just produce people like that. It’s luck that they appear at the right moment to enact change.”

While next-big-thing status is undoubtedly important for direct and institutional investors, for individual countries being part of that list is of secondary importance to growth itself. “The bigger the population of a country, the bigger is its GDP,” explains Kwan. “But that only tells you about aggregated output at a country level—for individuals, their quality of life or output level could still be very low. China will feel great when it overtakes the US to become the world’s largest economy, but Chinese workers will still only earn a tenth of what US workers earn.”

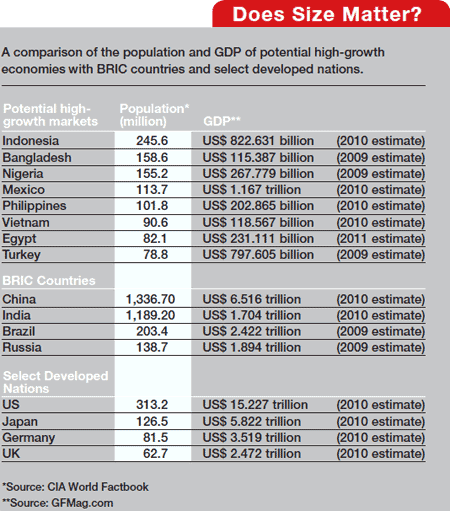

The various analyses conducted by Citi, Fidelity, Goldman Sachs, HSBC and others have different objectives and criteria. For example, Citi’s global growth generators include China and India, while other studies focus on non-BRIC economies in a bid to find the next big thing (see chart, p23, for acronym explanations).

Nevertheless, there is inevitably some overlap in predictions of which countries will enjoy success in the coming years. The greatest agreement is on Indonesia, which is identified by all four reports. “Assuming there is not wholesale political change, in 10 to 20 years’ time Indonesia will be a G7 or even G5 member,” says Kwan.

|

|

Ash, RBS: Countries that don’t invest in infrastructure could stymie development |

Indonesia has cleaned up much of its corruption, established good governance and strong educational infrastructure; and has good demographics, an abundance of raw materials, stable economic fundamentals and a commitment to reform and competition, according to Ngo. “Moreover, its level of debt is falling, its fiscal deficit is low, inflation is falling, and there is a high savings rate,” he says. “It looks destined to be one of the world’s leading global economies.”

Nigeria is selected by three studies—Citi expects it to be the world’s sixth largest economy by 2050. “Nigeria has a large young population, raw materials, 35% arable land and a stabilizing political system,” notes Ngo. Egypt, Vietnam and Turkey are also highlighted in three analyses. “Turkey is enjoying its longest-ever period of political stability and has a government that has a vision to double GDP in the next decade and is devising plans accordingly,” explains RBS’s Ash.

Other countries mentioned more than once include Bangladesh, Mexico and the Philippines. Left-field choices include Iran and Iraq (where some would say there are simply too many unknowns) and Mongolia, which Ngo says can expect growth of 10% a year for five years and 7% a year for the following 40: “Its location next to China, huge mineral wealth and small population will make it wealthy, but given its size it will never be globally important.”

Therein lies the problem for aspiring BRICs: The BRICs came to prominence partly because of their size. “China has become one of the world’s largest economies because it has the largest population,” says Kwan.

Of those countries cited more than once, Indonesia has the largest population—at 245.6 million, and the second highest GDP—at $822.6 billion in 2010. Mexico has the highest GDP—at $1.17 trillion, but a smaller population of 114 million. Turkey had GDP of $797.6 billion in 2009 but the smallest population—at around 79 million (see chart, left, for population/GDP comparisons).

As a contrast, all of the BRIC countries have above-trillion-level GDP—ranging from around $6.5 trillion for China and $2.4 trillion in Brazil to around $2 trillion for Russia—and populations that range from 1.3 billion in China and 1.2 billion in India to 140 million in Russia. All four countries make the top 10 list of the largest countries worldwide by population, according to UN data, along with the US, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh and Japan. Size does matter, but is clearly not the only thing that governs sustained growth.