THE NEW WORLD POWERS

The coming decade will witness a fundamental rebalancing of economic power, setting the stage for this to become the Asian Century.

By Harold L. Sirkin

It is clear to almost everyone that the center of economic gravity will continue to shift from the United States and Western Europe to Asia and Latin America during the next decade—and well beyond. To nobody’s surprise, given their size and rapid growth rates, China and India are driving this dramatic change and will be the main beneficiaries, followed by Brazil, Mexico and other rapidly developing countries. Vietnam may also loom large, and Eastern Europe could see a boom.

While another recession cannot be ruled out, the globalization trend will continue and even accelerate, with companies from everywhere competing for everything: markets, customers, talent, technology, financing, raw materials.

|

|

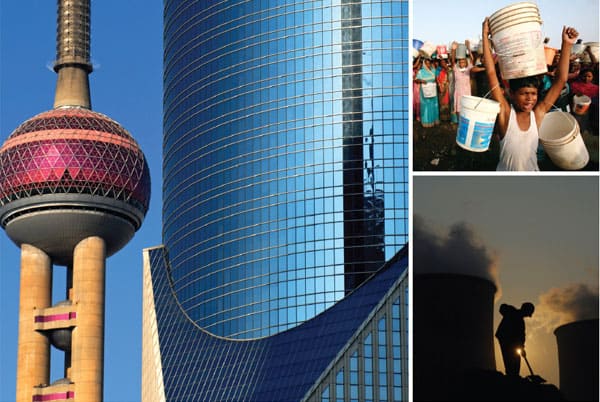

A study in extremes: China and |

In tandem with this development, financial institutions also will have to focus more on the rapidly developing economies (RDEs) of Asia, Latin America and Eastern Europe. This will put pressure on lenders and investors to increase their knowledge of the legal and cultural landscape so they can tailor their products to the needs of their new clients and manage their portfolios properly. This will also put pressure on China and other RDEs to increase financial transparency, better protect property rights and reduce controls on foreign investment.

China and India both scored poorly on The Wall Street Journal’s 2009 Index of Economic Freedom, with virtually identical composite scores of 53.2 and 54.4 respectively (with 100 being the best possible score). The report takes particular aim at “China’s complex financial system…tightly controlled by government,” pointing out that the country’s four state-owned banks account for more than 50% of total assets, while foreign banks “face burdensome regulations,” and foreign participation in capital markets is limited.

In India, state-owned banks control more than two-thirds of the commercial banking industry, and according to the report, high credit costs and scarce access to financing still impede development of the private sector. “Along with other restrictions, foreign banks…may not directly or indirectly retain more than 5% equity stake in a domestic private bank,” the report adds. While India’s stock market is one of Asia’s largest, foreign participation remains limited.

Whether historians one day will dub the 21st century the Asian Century remains to be seen. The 20th century became known as the American Century because the United States became the world’s dominant power, economically, militarily and ideologically. The American dollar became the de-facto international currency. “Made in USA” products were valued above others. After playing a crucial role in the fight to defeat the Axis powers and wearing down the Soviet Union during the Cold War, the US became the world’s only superpower. And the “American ideal”—freedom, opportunity and equality under the law—became the standard to which people everywhere aspired.

This is a hard act to follow.

A Long Way To Go

For all its prowess at making things, China is nowhere near ready to assume such a mantle. Even in the economic sphere, it has many hurdles to overcome: shortages of natural resources, environmental issues, a large and inefficient bureaucracy, inadequate protection of intellectual property, a tightly controlled financial system and inadequate systems to maintain production quality.

India faces equally substantial hurdles. Perhaps most important, the country has not yet developed the infrastructure needed to unleash its potential. It also has an underdeveloped system for delivering public services and a crippling system of labor and agricultural regulations.

Both countries must also continue to deal with extensive rural poverty. China has an estimated 100 million to 130 million people earning less than $1.25 a day, the minimum benchmark set by the World Bank; 54% of India’s population falls below the World Bank’s benchmark. Industrial power alone cannot solve these problems. Yet China and India are the teams to watch.

China’s economy, already the second largest in the world in terms of industrial output and third largest overall, will continue to grow at many times the rate of most developed economies, at least for the foreseeable future: 10% to 11% per year, compared to a likely 2% to 4% per year in the United States. And while the country still faces widespread rural poverty, the number of millionaires in China is expected to double in the next five years, to nearly 800,000, according to estimates released recently by the Boston Consulting Group’s Frankie Leung and Holger Michaelis. The combined wealth of these potential investors, according to the estimate, would exceed $7.5 trillion.

China’s manufacturing capabilities also will improve, as it acquires companies and capabilities worldwide and continues to develop its own science, engineering and management talent. Like Japan and South Korea before it, Chinese manufacturers will stop being mere copycats and become world-class innovators.

Another big plus for China will be its infrastructure, a past weakness. To stimulate the economy, the government has been investing heavily in infrastructure. As a result, in another 10 years China is expected to have 100 new airports and 186,000 miles of new roads, and subways in at least 250 cities. These and other infrastructure investments will help China become even more competitive in the decades ahead.

Coming out of the recession, China is uniquely cash rich, as are many Chinese companies, which are likely to use some of their cash to acquire weakened Western businesses.

India’s unique strengths should not be overlooked, either. India’s growing prowess in engineering and information technology, for instance, is a long-term trend. As India’s National Association of Software & Service Companies (Nasscom) wrote in a recent report, “With a young demographic profile and over 3.5 million graduates and postgraduates that are added annually to the talent base, no other country offers a similar mix and scale of human resources.”

Recession Provides Springboard

Not every Chinese and Indian company had a boom year, of course. Many struggled, like companies elsewhere. Those that were highly leveraged prior to the start of the recession were forced to reduce costs, restructure debt and, in some cases, sell off assets to improve cash flow. Companies highly dependent on exports also were battered.

But many Chinese and Indian firms, including several companies the Boston Consulting Group identified in 2009 as among the 100 top “global challengers,” found ways to gain during the recession. Companies with healthy balance sheets when the downturn began grew through mergers and acquisitions. Consumer-goods companies gained by selling new products designed for their domestic markets.

|

|

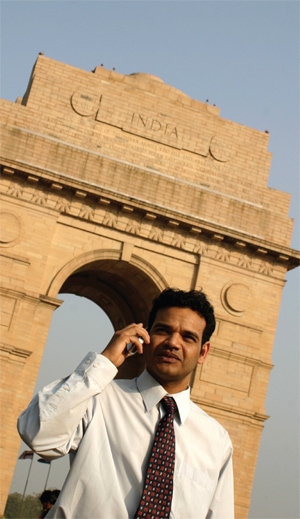

Sirkin: Many Chinese and Indian firms |

Although the “outbound” M&A; activities of the BCG 100 global challengers decreased overall during the recession, the crisis created an opportunity for companies to make important acquisitions at favorable prices. Many took advantage. Moving forward, others will do likewise.

Chinese home-appliance manufacturer Galanz, for example, created a special M&A; fund and assigned a group of senior executives to scour the world for distressed companies with strong R&D; capabilities and complete, advanced production lines. CNPC, China’s largest oil company, also saw the financial crisis as an opportunity for strategic acquisitions and set aside several billion dollars for that purpose.

While many companies wisely were cutting costs and preserving cash during the crisis, some global challengers were doing the opposite: making large investments in innovation and technology in the hope that this will springboard them to another level. BYD, for example—one of the world’s largest battery makers—entered the electric car business. The company had invested some $300 million in research since 2003 to create a mass-produced plug-in electric hybrid car that would not require specialized charging stations. BYD executives said the hard times facing the leading global auto companies, especially in the US, had reduced competition and made this the opportune time to move ahead with their plans. Taking the next step will no doubt require sophisticated global financing.

At the same time, many global challengers turned inward during the recession, tapping their home markets for growth. India’s Wipro and Infosys, top information technology service providers, had grown their businesses in recent years by providing IT outsourcing services to US and other Western companies. During the recession they increased their focus on the domestic market, just as the Indian government was increasing its investment in e-government initiatives.

Challenger companies also took advantage of available stimulus funds and investment and incentive programs to fuel growth during the recession and put themselves in good stead to thrive when the global recovery gains momentum. The Chinese government’s efforts to help domestic automakers included sales tax cuts, discounts and China’s own version of “cash for clunkers,” where rural residents who replace old three- and four-wheeled vehicles received subsidies of $300 to $440 to buy small, fuel-efficient cars. India also introduced measures to help domestic automakers, including tax cuts and lower gas prices.

What these examples show is that while most American companies were in a holding pattern during the recession, many challenger companies were prepping for the post-recession breakout. Partly as a result of this, the economic story of the next decade will be one of little-known companies from China, India and other rapidly developing countries gaining prominence—and in some cases dominance—in the global marketplace. This story began in the first decade of the 21st century. It will continue and accelerate in the years ahead.

Some of these challengers will become global leaders on their own. Some will do so by acquiring brands and technologies created by others. Many, history will show, will benefit from the Great Recession—being in the right place at the right time with a billfold full of dollars.

Just as globalization is far from over, the continued rapid growth of the global challengers—companies from everywhere competing for everything—is far from over. As the challengers become more numerous, more prominent and more sophisticated in the decade ahead, China, India and other RDEs will become not only the industrial hubs of the world, but possibly great financial centers as well. This will create new challenges and opportunities for everyone.

Harold L. Sirkin is a Chicago-based senior partner of The Boston Consulting Group (BCG) and co-author, with James W. Hemerling and Arindam K. Bhattacharya, of Globality: Competing with Everyone from Everywhere for Everything. BCG senior partners James Hemerling and David Michael contributed to this article.