FOCUS: CEE KAZAKHSTAN

By Jonathan Gregson

Kazakhstan’s bold recovery plan and its efforts to stabilize its financial sector are paying off as the country establishes itself as a regional hub.

If any country fits the broad concept of Eurasia, it is Kazakhstan. Lying at the very heart of Central Asia but also considered to be part of the broadened CEE region, it is closely linked to Russia through transport and energy infrastructure. More recently new pipelines and upgraded rail and road links to its eastern neighbor, China, have been built. Both culturally and geographically, it stands between Europe and Asia.

Its vast steppes are a continuation of those in neighboring Russia and Mongolia. And although its economy depends largely on the export of oil and metals—Kazakhstan has more natural resources per citizen than any other country—it is also home to the Cosmodrome at Baikonur, the world’s first and largest space launch-pad from which commercial satellites are regularly sent into orbit, and its commercial capital, Almaty, is rapidly becoming a financial hub for the whole Central Asian region.

Kazakhstan is also more closely integrated into global capital markets than most of its neighbors. Some of its largest companies are listed on Western stock markets, notably London, where mining giants Kazakhmys and Eurasian Natural Resources Corporation are FTSE 100 companies.

Until the global financial crisis struck, Kazakhstan’s resource-fueled economy was growing by close to 9% a year, and its financial institutions were riding high. But a combination of tumbling international commodities prices, loose lending by some of its banks and a collapse in its overheated real estate market brought the country’s banking system close to meltdown.

According to Gintaras Shlizhyus, an analyst at Raiffeisen Bank International (RBI), the root of the problem was banks’ exposure to real estate and construction. “Also, Kazakh bank funding was overreliant on highly leveraged and short-term foreign financing,” he says. “They had huge obligations to foreign investors, many of whom had to accept haircuts. In seven cases the government had to take over a bank in order to prevent systemic crisis,” he adds.

Olivier Descamps, managing director for Turkey, Eastern Europe, the Caucasus and Central Asia at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, says the government moved decisively to prevent a collapse of the financial system: “The government put in place a very large stimulus package to stabilize the banking system and stimulate infrastructure [construction],” he explains. “The country’s oil reserves stabilization fund was partially drawn on and transferred to Samruk-Kazyna, the national sovereign wealth fund established to manage strategic welfare assets from oil and gas to uranium and financial institutions.

Among other key moves, the wealth fund took over three failing banks and negotiated their restructuring with international creditors. “Money was pumped through the banking sector to address the acute problems faced by construction companies and SMEs,” Descamps adds.

|

|

Pulling it off: Kazkhstan’s economy recovered from the crisis swiftly, thanks to the rebound in oil, gas and other commodities prices |

According to Askar Yelemessov, chairman of the board of directors of Troika Dialog Kazakhstan, the local offshoot of the Moscow-based investment bank, an estimated $19 billion was taken out of the oil stabilization fund, known as the National Fund, and spent on liquidity support, frozen construction projects and support for infrastructure.

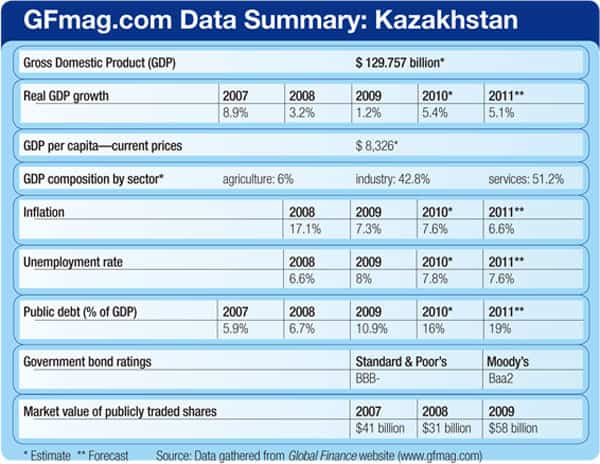

The shock tactics worked. GDP rose from around 1.2% in 2009 to above 6% last year.

“Kazakhstan pulled it off,” says Descamps. “That the economy recovered so swiftly is largely due to the rebound in oil and gas and other commodities prices. But besides having the means to pay, it also had the know-how and improvised successfully.”

Yelemessov cautions that the banks are not yet out of the woods. “The state-owned banks have had to absorb losses on private sector debt and are still working out nonperforming loans,” he says. “Total banking sector assets have shrunk by 20%, so it’s a new landscape.”

Descamps believes the banking system is stable and liquid but notes that banks are still wary of lending. “To generate further growth of the real economy, Kazakh banks should re-start lending to the private sector, but they are still licking their wounds from the crisis. In particular, they still have high levels of nonperforming loans, which need to be recognized and resolved before credit growth can resume,” he points out.

The so-called healthy banks that survived the crisis have been recapitalized, and there is better disclosure of bank ownership than there was before the crisis. The introduction of a 30% cap on foreign-exchange funding means that Kazakh banks are keener on having a more stable and balanced liabilities funding mix, too.

After the Shakeout

That the Kazakh economy is growing again is readily apparent. A sure sign, says Yelemessov, is that it’s impossible to get a table in a good restaurant in Almaty, the country’s financial capital, without calling in advance. Locals, meanwhile, are complaining that traffic congestion—always a clue to economic activity—is worse than in the old boom times. That growth seems to be built on firmer foundations. “The banks’ loans-to-deposits ratio has come down from 230% in 2007 to around 130% today,” observes Yelemessov. “That’s still high, but the share of liquid assets among all Kazakh banking assets has jumped considerably, to 27%. Savings in local currency deposits are on the rise and, as in most industrialized and emerging economies, there is lower appetite for borrowing.”

Evidence of this trend can be seen in the fact that many local companies are now bypassing the banks when they need funding and tapping directly into international capital markets, says Yelemessov, who expects almost no growth in overall bank lending in the next year or two.To help avert a future crisis, banking supervision could be strengthened, Descamps notes. Although there has been some progress recently, “the supervisory and regulatory framework is still not strong enough, corporate governance issues persist, and there is a lack of efficiency in risk management,” he says. Looking ahead, he sees one of the key questions being, How can the state engineer its exit from owning big commercial banks? Given the large role the state continues to play in the economy, he suggests that a gradual reduction of that role would be a way forward to optimize the country’s potential competitiveness.

Having recently experienced how rapidly hot money and portfolio investors can exit, Kazahkstan is now looking to attract more foreign direct investment (FDI). “In seeking to modernize the economy, the government’s priority is to attract long-term strategic investors that bring technology and know-how as well as capital,” says Shlizhyus. Much of this investment will come from the oil majors and mining corporations that need to continue funding long-term projects. In that respect, “Kazakhstan is very well placed,” says Descamps, “between Russia and a resource-hungry China.”

And Kazakhstan is coming up with the goods. In terms of bringing on additional oil production capacity, Yelemessov notes, Kazakhstan as been among the top six countries worldwide for the past 10 years or more. But the local economy is not getting the full benefit of Kazakhstan’s growing oil production because more than half of current crude oil production comes from Western companies and around a quarter comes from Russian and Chinese companies combined. Only 20% is pumped out by the Kazakh national company.

“Both the oil majors and regional mining players will be making more investments in order to increase production yet further,” Yelemessov says, adding that in terms of allowing access to subsoil resources, Kazakhstan is far more liberal than most countries, ranking fourth worldwide behind the USA, Brazil and Canada. Its openness to foreign companies may be contributing to the success of its efforts to attract long-term investment. In relation to the size of its economy, Kazakhstan has received 12.5 times as much FDI as its much bigger neighbor, Russia.

The volume of foreign investment does not tell the whole story, though, says Descamps, who adds that there is a need for a more level playing field between three stakeholders. “The state plays a big role but should not arbitrarily distort market mechanism competition,” he asserts. “The oligarchs must move on from defending their industries to competing more efficiently; and strategic foreign investors can bring a lot of what the country wants in terms of new technologies, added value and management skills.” He notes that the authorities are aware of such calls for a level playing field and are keen to keep existing strategic investors on board.

“Diversifying from being such a resource-dependent economy is the next challenge,” says Descamps, who points to the need for more diversification, more private sector activity and further investment in agriculture, transportation and energy efficiency to sustain recovery.

That message may now be getting through. “The Kazakh government is serious about promoting diversification and SMEs,” says Shlizhyus, “but it will be a long process.”

“To generate further growth of the real economy, Kazakh banks should re-start lending”

“But they are still licking their wounds from the crisis. They still have high levels of nonperforming loans” – Olivier Descamps, EBRD

Haste is needed, meanwhile, to address Kazakhstan’s infrastructure shortfalls, especially in its electricity and transportation networks, where the government is taking the lead but with considerable support from the multilateral agencies. “Last year the EBRD invested around $900 million in Kazakhstan,” says Descamps. “Out of that we put $300 million into transport and logistics, with a big chunk of funds aimed at the restructuring of the railway network—especially on separating freight operations from the passenger transport services.”

“We are also looking at renewable energy opportunities as part of the solution to relieve energy shortages in Kazakhstan. There exist issues of energy efficiency and clean technologies, as well as considerable waste in the system. The power sector contains some key challenges to be addressed, and it’s promising that private investors are coming in, realizing that they could make money on addressing these challenges.”

That could mean more public-private partnerships in future, Descampes adds. “There has been a lot of talk about PPPs, but thus far projects like the much-needed East-West road connection or the light railway for Almaty have not gone ahead.”

While international investors still view Kazakhstan primarily as an energy play, those in neighboring countries see things differently. China has become a major strategic investor, says Shlizhyus, and not just because it imports Kazakh oil down trans-border pipelines. “It is equally interested in Kazakhstan as a transportation corridor, a source for nuclear energy and a market for construction materials,” he comments.

Other former Soviet republics, including Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, now look to Kazakh banks and corporates as important investors, Shlizhyus adds. That development is a testament to the fact that, thanks to its oil and mineral wealth, Kazakhstan has been able to weather the crisis and repair its financial sector so effectively that it is now set to become the financial hub for the whole Central Asian region.

EBRD Extends Its Reach

Later this month, government officials, business executives and NGOs from across the CEE region—which is now often considered to extend beyond Central and Eastern Europe to encompass Russia, the Caucasus and Central Asia—will assemble in Kazakhstan’s new capital city, Astana, for the 20th annual meeting of the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD).

Founded shortly after the Berlin Wall came down, the EBRD’s focus is on helping former Soviet satellites such as Poland and the newly independent states that emerged from the dismantling of the Soviet Union go through the transition to becoming more liberal and competitive economies. Many have done so successfully over the past 20 years and are now full EU or even eurozone members.

“The Czech Republic, for instance, graduated from being a recipient of EBRD assistance before the onset of the financial crisis—which proved a major setback for many other CEE countries like Hungary and the Baltic States,” says Larry Sherwin, deputy director of communications at the EBRD. Responding swiftly to the crisis, the EBRD took on more projects. “The bank’s annual business volume has increased significantly, from about $5.9 billion in 2008 to $9 billion last year,” says Sherwin. “We anticipate it staying at this level for the next few years.”

As the core CEE countries have become more stable, the EBRD’s activities have shifted geographically. “The bank’s focus is moving east and south,” says Sherwin, “towards Russia, Central Asia, the Caucasus and southeastern Europe, which is where our expertise is most needed.”

The Astana 2011 annual meeting will explore issues faced by many CEE countries, notably the economic weaknesses revealed by the crisis and how these affected policymakers’ views on economic reform. Also on the agenda are common themes that the EBRD has long championed: fostering entrepreneurship, women’s place in business, building judicial capacity, striking the right balance between state and private sectors, attracting international finance to renewables and energy efficiency projects, and developing local capital markets and more lending in the local currency.

The EBRD’s role will also be affected by other changes taking place across the region, including the recently agreed customs union between Russia, Kazakhstan and Belarus, which will enhance economic prospects for Belarus in particular. “The size of the market fully open to Belarusian products will grow more than tenfold,” says Podkovyrov Vladimir Ivanovich, chairman of the board of JSC Belagroprombank. “It is considered a serious boost to the Belarusian economy.” Gintaras Shlizhyus, an analyst at Raiffeisen Bank International, says the strategic aim of the customs union is to create a unified economic area that will “focus on the benefits of reintegration between industries in separate countries that worked closely together in Soviet times—and in many cases still do.” As the countries themselves forge stronger economic ties, the role for development banks such as the EBRD will diminish. In the initial stages, however, says Shlizhyus, “there will be more costs than benefits.” While that remains the case, the development banks will still have plenty to do.