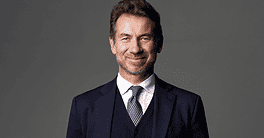

Christopher Hodge, chief US economist at investment bank Natixis, shares his thoughts regarding the forces shaping the US economy. With a career spanning the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the US Department of the Treasury, and hedge funds, he offers a rare public and private perspective on today’s policy-driven landscape, the growing risk of an economic slowdown, and how recent policy decisions may be making it worse.

Global Finance: How did fiscal and monetary policy interact during your time at the US Department of the Treasury?

Christopher Hodge: There was a high degree of coordination between the Treasury and the Federal Reserve, but decisions about where on the yield curve to issue debt are solely within the Treasury’s purview. There have been accusations that the Treasury [under Secretary Janet Yellen] engaged in “stealth quantitative easing” by front-loading issuance at the short end to create scarcity in the belly of the curve. But in my view, most of the decisions under Secretary Yellen were consistent with historical norms. During my time at both the Treasury and the Fed [2020-23], I never observed any erosion of institutional independence or overstepping of mandates.

GF: Is the recent volatility in the US dollar cyclical or structural?

Hodge: It’s a bit of both, cyclical and potentially structural. The dollar remains historically strong; the trade-weighted index recently hit levels not seen since the Plaza Accord [in 1985], so some correction was inevitable. After “Liberation Day,” we saw a broad selloff in the dollar, equities, and treasuries. That reflected growing skepticism about the US as a trading partner, a military ally in Europe, and as a generally reliable global actor.

With foreign reserves currently just over 50% in dollars, some erosion is possible. I don’t see one clear beneficiary—whether it’s the euro, yen, Swiss franc, or gold—but more of a general diversification away from the dollar. And when the president is tweeting things like threats of sanctions or tariffs on countries coordinating with BRICS or pursuing “anti-American” policies, that kind of unpredictability makes foreign reserve managers think twice about their exposure to the dollar.

GF: How have tariffs and recent economic shifts reshaped corporate treasury priorities around liquidity and working capital?

Hodge: One thing that’s really struck me is the increase in volatility—especially at the short end of the curve—and how markets seem increasingly comfortable with it. The Fed used to act as a backstop, essentially the buyer of last resort, but now it’s clearly trying to reduce its footprint in US debt markets. We’ve seen what you might call mini stress tests, and the market has proven remarkably resilient.

That cuts two ways. On one hand, this tolerance for volatility could make markets more robust going forward; on the other hand, it could lead to underpricing of larger systemic risks. I’m not sure where I land on that question, but what’s clear is that markets have absorbed a great deal of volatility, whether policy-induced, trade-related, or tied to the Fed slowing its quantitative tightening.

GF: Soon, someone will have to pick a new Chair of the Federal Reserve. If it were up to you, what qualities would you look for?

Hodge: I’d look for someone respected by both the markets and within the Fed, with a reputation for nonpartisanship and intellectual curiosity. The ideal candidate should lead with data, not be tied to hawkish or dovish labels, and demonstrate flexibility as conditions change. Christopher Waller fits this profile; he’s been both hawkish and dovish as needed and is considered an intellectual thought leader. I tend to agree with his current view that, under normal circumstances, the Fed should be cutting rates, which aligns with what standard economic textbooks recommend.

Waller is already on the Federal Open Market Committee, and last September, when the Fed cut rates by 50 basis points—a move criticized by the Trump campaign at the time—he did not dissent, reflecting his dovish stance then. And he’s dovish now. His record shows that he resists political pressure and lets the data guide him. Among public candidates, I think he stands out as the best choice.

GF: Natixis recently hosted an event highlighting the variety of views on AI’s impact on jobs and the global economy. What’s your perspective on job loss? Do you foresee widespread destruction, or a more balanced effect?

Hodge: I think the doomsaying over AI is probably overstated. Twenty years from now, jobs that we can’t even conceive of right now are going to exist and displace people in the workforce. But that’s no different than any sort of revolutionary technological change that we’ve seen throughout history. So I’m more optimistic than most. AI will certainly displace some roles, but will also generate new kinds of work. While disruption is real, it’s matched by opportunity. Which proportion of each is the real question mark, but I tend to embrace technological changes rather than be a skeptic.

GF: In corporate finance, do you expect AI will significantly shrink banking and legal teams?

Hodge: AI can rapidly automate tasks like credit analysis and due diligence, making some roles redundant. However, this allows talent to reallocate toward higher-value activities, potentially raising productivity. While short-term job loss is inevitable, especially for repetitive tasks, new opportunities should arise that balance the impact. The transition brings challenges, but also significant gains, particularly for those adaptable to new roles.

GF: How much do you look at consumer and corporate debt levels, and how do they shape your outlook on the economy?

Hodge: We expect sluggish growth through the rest of 2025: especially slowing growth in Q3, around 1% in Q4, and then returning to trend growth of 1.6% to 1.8% in 2026. It’s subpar, but not a meltdown.

On the corporate side, balance sheets remain solid, especially for firms that accessed capital markets during the pandemic. Many refinanced or extended maturities, so the feared “maturity wall” hasn’t materialized. Even bilateral loans have largely been pushed out to smooth the cycle.

On the consumer side, there’s a clear bifurcation. The top 20% of earners are still spending, and overall, balance sheets are relatively strong. But the bottom 40% are under pressure. We’re seeing rising delinquencies in auto, mortgage, credit card, and student loans. Precautionary savings are ticking up, incomes remain stable, but spending has softened.

This kind of pullback is typical late in the cycle; businesses get cautious on sales, consumers on job security. We expect growth to bottom out in Q3, but the underlying balance sheet strength should help prevent a downward spiral.

GF: Can the US plausibly grow out of its $36 trillion debt load?

Hodge: Absolutely. Countries do this all the time. If you assume 3% growth forever, sure, the debt trajectory looks better. But the US’s potential growth is closer to 2%, and at that rate, debt will keep rising. Neither political party is seriously addressing the issue, and the Social Security trust funds are on track to be depleted by the early 2030s, possibly sooner. I think by 2028 this will become a major political issue; whoever takes office then will inherit a ticking fiscal time bomb.

We’re already seeing signs of strain. Of the $36 trillion in total US debt, around $29 trillion is held by the public and about 32% of that is held by foreign investors. Even a modest pullback in foreign demand could raise the term premium and borrowing costs.

And we haven’t done anything meaningful to bend the cost curve. The Department of Government Efficiency barely touched the problem; federal salaries, for example, are just 3% of discretionary spending. Without addressing entitlements, the debt will keep ballooning.

One chart I often share shows how the number of workers per Social Security beneficiary has collapsed, from 25 in the 1950s, to a projected 2.1 by 2030. Add in slowing immigration and other demographic trends, and the idea of growing our way out of this starts to look far less plausible.