GUNNING FOR GROWTH

By Gordon Platt, Antonio Guerrero and Anita Hawser

Global Finance presents its annual report on the performance of the world’s central bank governors.

Central banks of most of the major global economies are pulling out all the stops in an effort to stimulate growth. Many of them reduced short-term interest rates close to zero four years ago. And the US Federal Reserve, for one, has pledged to keep rates exceptionally low for years to come.

Low interest rates haven’t been enough, however, to meet the goal of a stronger recovery and lower unemployment rate, with stable prices. At its most recent meeting, the policy-setting Federal Open Market Committee said: “Many members judged that additional accommodation would likely be warranted fairly soon unless incoming information pointed to a substantial and sustainable strengthening in the pace of the economic recovery.”

The FOMC had already provided additional accommodation at its previous meeting by announcing the continuation of the maturity extension program, known as Operation Twist, through the end of 2012. The Fed is selling Treasury securities maturing in three years or less and buying notes and bonds with maturities of six years to 30 years, in an effort to keep long-term rates low. However, many members of the committee stated at the latest meeting, which ended on August 1, that at the end of 2014, they expected the unemployment rate to still be well above its long-term normal rate, and that inflation would be at or below the Fed’s 2% target rate.

Central bankers around the world are keenly aware that Japan has suffered through nearly two decades of subpar economic growth, despite rock-bottom interest rates and numerous asset-purchase programs by the Bank of Japan in its fight against deflation. The major economies appear to be moving in sync toward a global slowdown, and the central banks are in danger of running out of ammunition to counter this trend. Meanwhile, commercial banks are struggling to clear away nonperforming loans from the last downturn and meet higher capital requirements.

When an automobile’s transmission mechanisms are broken, pushing the accelerator to the floor doesn’t produce forward motion. Monetary policy has lost some of its efficacy, yet financial markets remain addicted to more accommodative policies from the central banks.

By extending swap lines and providing unlimited short-term funds, central banks can cope with liquidity problems. Filling up the gas tank doesn’t help, however, if the transmission needs fixing. The Bank of England in August launched a Funding for Lending Scheme designed to coax banks to increase the availability of business loans and mortgages. The more the banks lend, the more they can borrow at low rates from the central bank.

As central banks enact more quantitative easing, these exercises may be becoming less effective. The monetary authorities are also taking a risk that debt monetization, or “printing money,” could ultimately lead to runaway inflation and currency debasement, according to some economists. Jeffrey Lacker, president of the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, at this year’s FOMC meetings argued against further stimulus because, he says, it is unlikely to stimulate growth much and could generate a sustained surge in inflation.

Meanwhile, Europe’s debt crisis continues to fester, and Greece has asked for more breathing space from the austerity imposed as a condition for its rescue funds. With countries such as Spain and Italy being forced to pay unsustainably high interest rates, the ECB is expected to step in to buy their bonds.

Even the big emerging markets, the so-called BRIC countries, which once could be counted on to take up the slack, are experiencing slower growth and introducing stimulus programs. The Bank of Canada is the only major central bank that is contemplating higher interest rates to slow a strong economy.

Central bankers in the developing countries are fearful of the spillover effects of Europe’s crisis on their exports, as well as the “hot money” flows that destabilize their economies as the developed world prints more money.

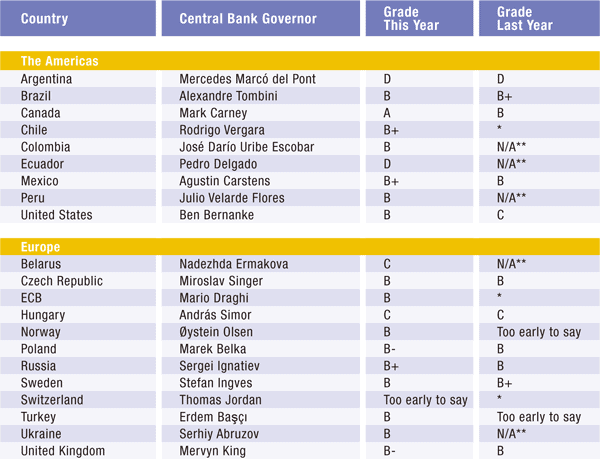

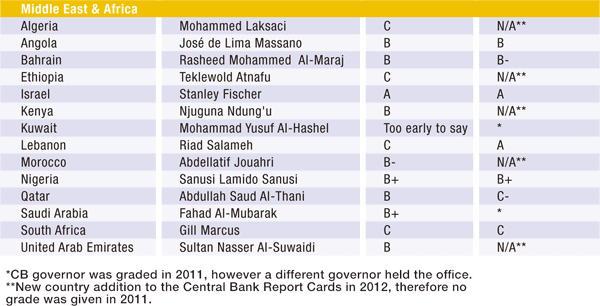

Global Finance has been publishing Central Banker Report Cards since 1994, grading central bankers of key countries on an “A” to “F” scale. The criteria include inflation control, economic growth, currency stability and interest rate management, as well as the determination of central bankers to protect their independence in the face of political interference.

Central Banker Report Cards 2012