If you cannot measure it, you cannot manage it.

The clock is ticking for firms to measure and report on the risks to their business from climate change, while regulators pile on additional pressure to quantify and mitigate this nebulous but increasingly urgent threat.

More than 7,300 major natural disasters were recorded by the UN between 2000 and 2019, at a cost of nearly $3 trillion. This compares with 4,200 disasters at a cost of $1.6 trillion in losses during the prior 20 years. Climatechange is now rarely out of the headlines, with floods in Europe and wildfires in Canada among the latest devastating events.

No longer a risk of the distant future, a failure to tackle climate-change risk could cost the world $1.7 trillion a year by 2025—according to a report released in March by New York University Law School’s Institute for Policy Integrity. In what its authors believe to be “the largest-ever expert survey of the economics of climate change,” the “overwhelming consensus” among the 738 economists canvassed concludes that inaction will be costlier than action, and that “immediate, aggressive emissions reductions are economically desirable.”

Quantifying Financial Risks

The primary goal of the Paris Agreement is to keep the average global temperature rise below 2º C (3.6º F), preferably limiting it to 1.5º C (2.7º F), compared to preindustrial levels. Most countries have also declared ambitions to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2050—with many of them setting it into law since signing the accords in 2015.

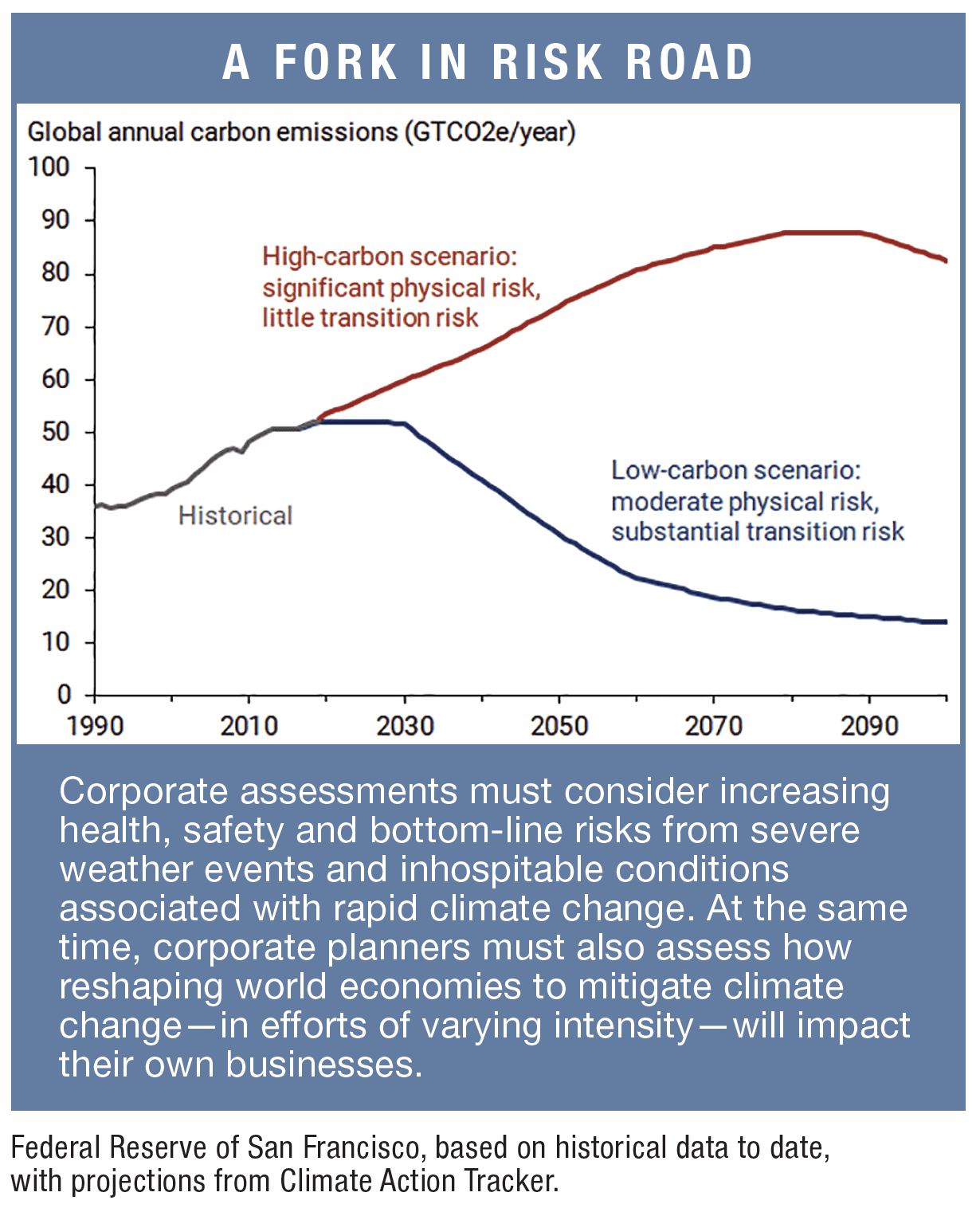

Climate risks are grouped by the UK’s Financial Stability Board (FSB) global Task Force on Climate-Related Financial Disclosures into two main categories: physical and transition risks. The former are defined as having “financial implications for organizations, such as direct damage to assets and indirect impacts from supply chain disruption.” These may include changes in resource availability and quality; food security; and impacts of extreme temperature changes on operations, supply chains and personnel safety, as well as legislative and other risks stemming from these hazards.

Transition risks are those associated with the move to a low-carbon economy. These may include “extensive policy, legal, technology and market changes to address mitigation and adaptation requirements related to climate change.”

Each set of climate risks has long-term implications, difficult to quantify and therefore to mitigate. Financial regulators are showing progress, however.

In December 2020, the ESG Subcommittee of the US Securities and Exchange Commission’s Asset Management Advisory Committee issued a preliminary recommendation that the commission mandate ESG disclosure standards as adopted by corporate issuers. European supervisory authorities have released guidance on assessing and managing climate risks and conducted stress-testing exercises. These moves are in line with other, similar developments, including those by the Bank of International Settlements and the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening of the Financial System.

The UK’s FCA has also outlined new climate-related disclosure requirements. Recognizing the challenges of assessing the risks, the FCA along with the Bank of England’s Prudential Regulation Authority created the Climate Financial Risk Forum (CFRF) to help build disclosure capabilities. Its guidance covers climate-related disclosures, risk management and scenario analysis, as well as opportunities for innovation.

The CFRF’s 2020 Guide to Climate-Related Financial Risk Management states that measuring the impact of transition and/or physical climate-related financial risk drivers on key financial metrics requires quantification through a variety of transmission channels (including credit risk, market valuation and operational risk), and that “ultimately, a firm will be looking to measure the aggregate impact of a climate scenario or shock into their income statements and balance sheet as well as other key financial metrics, such as risk-weighted asset ratios or regulatory capital buffers.”

The approach will vary across the financial sector, of course, due to varying internal performance models. The CFRF also advises firms to “consider suitable time horizons,” the impacts of which vary according to business sector and their physical or transition risk.

“This is because the short-term temperature outcome is already locked in, as it is dependent on past emissions,” write the guide’s authors. “The most significant and extreme physical impacts are likely to arise only over several decades. Multiple emissions pathways are therefore needed to explore the full range of potential physical impacts in the long run. Shorter time horizons, therefore, may allow firms to construct alternative transition scenarios which carry the same physical scenario though, whereas longer term horizons may allow firms to explore a richer combination of both multiple transition and physical outcomes.”

Growing Litigation Risks

Major events and high-profile brands are attracting increasing attention from activists who feel that more needs to be done. Many have already gone to court in Europe to force governments and businesses to take more action or pay damages.

A July study from the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment at the London School of Economics and Political Science found 1,006 climate-related litigation cases that have been filed since 2015, compared with 834 over the previous 28 years.

Nigel Brook, a partner at law firm Clyde & Co., warns to be mindful of the implications. “Already this year, we have seen a case brought against French supermarket chain Casino by indigenous peoples from the Brazilian and Colombian Amazon and French and US NGOs, seeking the relatively modest sum of $3.7 million. The claimants allege that Casino sourced beef from local suppliers who have contributed to 50,000 hectares of deforestation,” he explains. “The case, which relies on the French statutory ‘duty of vigilance,’ may, if successful, encourage others to bring similar cases against companies for environmental violations in their supply chains.”

Supply chain emissions are much higher than the direct emissions from many companies’ own operations, wrote the authors of a Boston Consulting Group (BCG) blog post in January. “By implementing a net-zero supply chain, companies can amplify their climate impact” and at the same time “accelerate climate action in countries where it would otherwise not be high on the agenda.” Decarbonization of the supply chain, and therefore the measuring the process, is not commonplace, however. It is difficult.

Historically, climate change has been viewed through the corporate social-responsibility lens; but that approach is increasingly considered to be insufficient.

Specialists at Deloitte Australia focus, in an industry note, on the value of connecting the climate-risk team to the financial-accounting team to create a “combined effort toward a combined end” when addressing climate risk and financial statement impacts.

Deloitte Sustainability and Climate Change manager Auzita Jarrah and partners Chi Mun Woo and Paul Dobson recommend debating “materiality of climate risks in the context of financial statement line items. This includes quantitative and qualitative impacts that could influence investor decisions, they write. “Start with: What would your future cash flow projections look like? How and when will your existing assets be replaced? Do you need to provide now for the cost of future action arising from climate-related risks? Can your debtors pay?” Then, “Make a forward-looking assessment.”

Assessing the level of detail for relevant disclosures and quantifying impact on financial statement line items, they write, “can be done through climate-scenario analysis, ESG risk evaluations, stress tests, sensitivity analysis or credit-risk assessments to assess business implications of physical and transitional risks and opportunities.” Finally, ongoing reviews of assumptions made will ensure that statements “continue to reflect the organization’s risk profile.”

Risk experts at Oliver Wyman management consultancy also advocate climate-scenario analysis as a “useful tool” for assessing climate-change exposures, described in a 2019 paper as a “what-if” analysis offering. They also say many firms are developing scenario-planning capabilities or plan to do so soon; and they recommend assessing transition risk based on representative scenarios while extrapolating name-level information “to balance [the] accuracy, comprehensiveness, and workload.”