Product recalls are rising and have evolved into a major financial risk. Here’s how to manage and mitigate the impact.

Product recalls can damage a company’s brand, throw operations into crisis and deal a body blow to earnings. Just one can finish off a smaller, less diversified company.

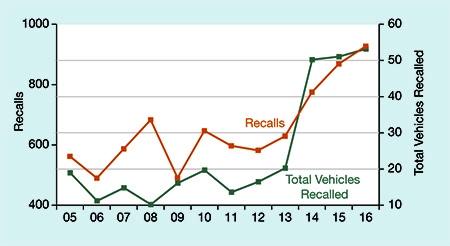

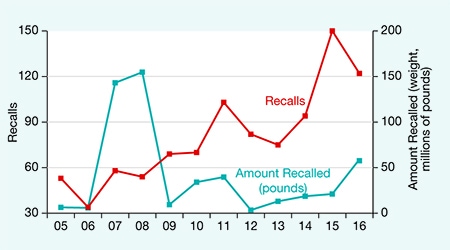

On top of that, the rate of incidents is increasing. Both automobile- and food-safety-related cases have hit record highs in the US in recent years, with 927 separate auto recalls (53.2 million vehicles) in 2016, and 150 food recalls by the Department of Agriculture alone in 2015. The European Commission recorded more than 2,400 nonfood consumer-product notifications in 2014, versus just 388 in 2004.

“Today, when [recalls] happen, they can be more catastrophic because of the size of the settlements and how widespread the impact is,” says Karen Burns, assurance partner at California-based accounting and business advisory firm Sensiba San Filippo. At least 10 food companies issued voluntary recalls in June related to listeria. Three months later, Volkswagen announced it was taking a charge of $3 billion in the third quarter due to complications in its plan to buy back or retrofit 83,000 3-liter diesel vehicles. The charge brought the price tag for VW’s emissions-cheating scandal to some $29 billion and wiped out half of the automaker’s projected third-quarter earnings.

Recalls, then, aren’t just a once-in-a-blue-moon threat to a company’s earnings and, possibly, its long-run reputation, say lawyers, actuaries and crisis managers who have helped orchestrate recalls. Recalls are an ongoing financial risk that needs to be managed at the highest levels. Manufacturing supply chains today are longer, involve more separate suppliers and are frequently global. Laws and regulations mandating recalls and assessing fines have become more stringent: The 2011 Food Safety Modernization Act in the US was a watershed, shifting regulators’ focus from responding to contamination to preventing it. Social media, meanwhile, has changed the news cycle, rapidly spreading and amplifying reports of product defects, contamination and mislabeling, while also stoking consumer disaffection.

“Companies must approach their business as ‘when will I have a recall, not if,’” says Burns. “If you’re producing products for the public, it will happen.”

Smart Planning

Quality control, alongside a culture of safety and awareness, is the first line of defense. Blue Bell Creameries, the nation’s third-largest ice cream maker, was thrown into crisis in 2015 when the Centers for Disease Control linked its products to a listeria outbreak. That recall was utterly avoidable; Blue Bell, it turned out, had found the bacteria in one of its plants two years earlier but hadn’t eradicated it.

Companies also can purchase recall insurance to cover such risks. “Even with good quality control, defects and tainted goods can slip through,” says Kevin Velan, national product recall broking specialist at insurance broker Willis Towers Watson. Additionally, supply chains and products change, and coverage has to stay current with that evolution. “Always be sure you know what your out-of-pocket costs are,” says Burns. “Do an audit every year with your broker. You may think you’re covered for some things that you’re not.”

A “stock-throughout policy” can insure inventory and transport of goods from factory to retail outlet, while third-party coverage can protect a company in case its problem diminishes the value of its customer’s product. There are insurance products for business-interruption losses and for brand-rehabilitation expenses. Recall insurance, although it can strain a budget, is especially important for smaller and midsize companies, says Burns, because “recalls can and do put them out of business.”

Companies can set aside cash reserves to guard against the expense of recalls. “Budget for some bad stuff,” advises a former general counsel at a major food-products company, who asked not to be named. Some companies have a budget line for possible recalls—for example, a percentage of actual sales. Auto companies and large retailers are now typically doing this, says Velan.

Practice, Practice, Practice

One way to prepare for recalls is to rehearse the process: how to get the product back, how to destroy it and what’s needed to enter an insurance claim, with prescribed roles for everyone who has a responsibility under that process. Many companies hold mock recalls complete with press releases and employees playing “customers,” and some get their third-party suppliers to do so as well. “If your company does this every year, it’s considered a better risk,” says Brandon Sielen, national product recall brokering specialist, and Velan’s colleague, at Willis Towers Watson. The recall-response team—including the CFO, general counsel and chief risk officer—must be able to track activity across the supply chain, to pinpoint the problem and its solution.

Recalls vacuum up ready cash; so financial executives need a cash-flow framework that includes cash going in, loans and insurance costs. That way the company can monitor how the cost changes as the event develops. “Cash is king,” says Burns. “Nothing shuts you down faster than inability to pay your people. If all your cash is going to pay for the recall situation, you’re out of business.”

Cash flow is not as great an issue for large diversified companies; but smaller and midsize companies may not be so lucky, especially if a full plant shutdown and rehabilitation is required. In that case, executives must be ready to work with creditors—who don’t want their clients to go out of business—to keep the company running. Blue Bell was able to stay in business with the help of a $125 million loan from investor Sid Bass.

Early input from the lawyers is invaluable. By the time a threat of regulatory or legal action becomes clear, it may be too late. Counsel can help determine whether a real or possible defect, mislabeling or contamination triggers a recall or not. Counsel also can help decide what to say and when, especially about the origin and nature of the problem. “Think of the steps you are taking and how it looks,” says the former general counsel.

Don’t Play Dumb

Stakeholders—customers, regulators, insurers, lenders and creditors—must be informed quickly, through press releases, simple notifications and direct contact. “Better if they hear it from you,” Burns says. Insurers often will help: Some policies cover hiring a crisis-management advisor.

It’s easy to underestimate the time and expense involved, especially in the early days after the problem is discovered; Blue Bell’s travails were compounded by overoptimistic forecasts about the speed of cleanup. “Share information, by all means,” says the former general counsel. “But if you let your story morph, you taint the process and you could lose everything.”

Launching a voluntary recall rather than waiting for regulators to order it is a chance to shine. “That way you are in control,” says Burns. “It’s less costly than a mandatory recall. It earns you goodwill, and you can even make it into a heroic event for the brand.”

But to make it work, the company must focus on what’s right for the customer, not the cost. Companies that emerge from a recall the least damaged “are those that accept responsibility for their mistakes,” Willis Towers Watson’s Sielen says. “Companies that push back and deny culpability and turn it back on someone else are the ones that take the worst hit.”

Appearances also are important as a company deals with customers, regulators and other stakeholders. “When we came to a fork in the road in the process, we brought the regulators into the discussion,” says the former general counsel, who helped conduct a recall related to contaminated produce. “When the results of our testing came in, we invited them into the plant to advise us.”

Managing recalls is an unconventional skill for the finance function, but one that coming years will give CFOs more chance to exercise. Like natural disasters, they seldom sit still; cost and other impacts reveal themselves only over time. The finance team is forced to modify its estimates as the crisis unfolds. That means accepting your limitations. “The companies that do the best,” says Velen, “are the ones that are on board with the concept that nothing’s going to be perfect.”