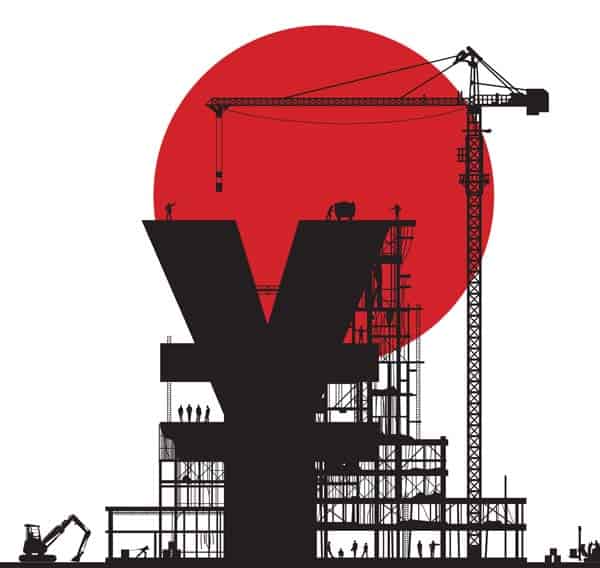

JAPAN SCRAMBLES FOR A FRESH START

Japan’s new government is working hard to find ways to rouse the country’s economy from its persistent malaise.

By Thomas Clouse

Japan is a country of economic contrasts. It is a nation of savers, yet its public debt is the highest in the developed world. It trades more with China than with any country in the world yet fears its neighbor’s rise. It is home to many of the world’s most innovative companies, but its financial system suffers from inflexibility. Japan transformed itself from a nation devastated by war to the world’s second-largest economy in the second half of the 20th century, and yet its economic policy produced one of the most popular case studies for poor macroeconomic management.

Japan emerged from World War II to produce remarkable economic growth over the four decades that followed, placing itself behind only the United States in terms of the size of its economy. Its meteoric economic rise, however, came to an abrupt halt when its overleveraged stock and property markets plunged in late 1989. The country’s policymakers were reluctant to recognize the severity of the losses and focused their recovery efforts on infrastructure investments. The economy limped along for years before the nation’s banks began to fail. The painful and expensive restructuring that followed in the late 1990s and early part of the past decade ushered in many necessary changes but failed to significantly revive the country’s economic growth, largely due to its vulnerability to external shocks. At the same time, infrastructure investments aimed at reigniting growth drove up the country’s debt. The failure of Lehman Brothers and ensuing global panic in October of 2008 dragged Japan’s Nikkei stock index to a 26-year low, and 2009 rounded out what is already being called Japan’s second lost decade.

It is against this backdrop that Yukio Hatoyama and his Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ) rose to power last fall, breaking the opposing Liberal Democratic Party’s almost uninterrupted 54-year hold on power. The DPJ appealed to voters with pledges to cut government bureaucracy and wasteful spending while implementing policies to spur domestic consumption.

Hatoyama’s proposed budget for the next fiscal year, which begins in March, increases social welfare spending by almost 10% to ¥27.3 trillion ($290 billion) and slashes funding for infrastructure projects by 18% to ¥5.77 trillion. Two of his most popular proposals, child-rearing subsidies and free high-school education, seek to alleviate two of the country’s most significant problems: low consumption and low birth rates. The measures would boost household incomes, and thus consumption, while encouraging young adults to have more children.

Uncertainty remains, however, about the effectiveness and affordability of these programs. In a recent report on the state of Japan’s economy, Tetsufumi Yamakawa, chief Japan economist at Goldman Sachs, wrote: “It is not necessarily clear what impact tax reforms will have in terms of boosting household income. The guidelines call for income to be transferred to households via childcare allowances and other childcare assistance measures, but this will be largely offset by reductions in or elimination of income/local tax deductions for dependents.”

The programs’ financial burdens could also dampen future economic prospects. Hatoyama’s proposed budget of ¥92.3 trillion ($1 trillion) is the largest in Japan’s post-war history. Furthermore, with the current economic conditions crimping government revenues, the bulk of the budget will be financed through debt issuance. This marks the first time in the post-war era that new debt issuance will outpace tax revenues. With public debt already approaching 200% of GDP, such massive outlays will be difficult to sustain and could eventually undermine confidence in government bonds, pushing up borrowing costs and creating a potentially dangerous debt cycle.

|

|

Yukio Hatoyama, Japan’s new prime minister, appealed to voters with pledges to cut bureaucracy and increase social welfare spending |

Japan Pins Hopes on Regional Trade

The government’s budgetary woes could worsen further as Japan’s population ages. Japan has the highest proportion of elderly in the world, with 22.1% of its population over 65 years old in 2008. At the same time, the country’s birth rate remains low, and life expectancy is increasing. The proportion of the population over 65 is expected to climb to over 30% by 2030, according to government estimates. The demographic shift will not only push up pension costs but reduce the number of participants in the workforce, lowering potential economic growth. Goldman Sachs estimates that the potential growth rate could fall from 1.5% currently to 0.5% by 2015 due to demographic changes.

Hatoyama hopes to compensate for this lost growth potential by promoting regional trade relationships and investing in green technologies, healthcare and tourism. Japan has thus far benefited from the tremendous economic growth of its neighbors, especially China. But, says Simon Collinson, professor of international business and innovation at the University of Warwick in the UK, “The strengths that Japan has had historically—automobile and consumer electronics—are the kinds of industries in which China is getting stronger. Being successful in these industries, up against the growth of capabilities of the Chinese economy and the plateauing of demand in Europe and the USA, will be a challenge.”

China is also working hard to promote its domestic capabilities in the industries mentioned in Hatoyama’s plan: green technology, healthcare and tourism. For this reason, lower trade barriers could bring increased competition.

Collinson does not believe Japan should shy away from integration but instead expand its industrial focus. “What a lot of people don’t know about Japan,” he continues, “is that its export success and part of the success of the economy is based on a fairly narrow set of industries, mainly automotive, consumer electronics and some areas of light engineering. The vast majority of Japanese industries, including pharmaceuticals and chemicals, are weak globally; highly dependent on domestic demand, domestic manufacturing, domestic suppliers; and still very locked into keiretsu structures.” Keiretsus are loose conglomerations of companies, which controlled many of the investment channels throughout Japan’s economic rise.

Greater regional integration could help Japan’s weaker industries to internationalize by encouraging investments overseas, as well as bringing more competition to Japan’s domestic market. But public sentiment, especially in Japan and China, could complicate those integration efforts. Relations between the two countries continue to face strain over historical differences, especially in regard to WWII. “The future, in my view, is very much about how well Japan overcomes its past with China, and vice versa for China, in order to build on the complementary features to create a regional economic power base,” explains Collinson. “The Asian bloc is very much where Japan should be focusing its attention.”

Financial Markets Face Challenges

While international exposure will make Japan’s companies more competitive, domestic financial structures also need to be improved, Collinson says. “The Japanese system did not restructure its financial markets as radically as it should have in the 1990s. Had it done so, you’d have much more capital flowing to small, high-tech start-ups and more radical areas of science and technology, where they’ve got a superb innovation base and wonderful R&D; at the corporate level,” he says.

The small, innovative companies to which Collinson refers have limited financing options. Japan has only a small Nasdaq-style stock exchange, and the country’s banks are reluctant to give out loans to such risky clients. The reasons for this reluctance are complex. Despite their strong deposit bases, Japanese banks generally compete heavily for lending to large corporate clients rather than extending loans to riskier small and medium-size enterprises (SMEs). The aversion to such lending prevents new companies from obtaining funding, which in turn prevents non-traditional industries from developing.

The government is making efforts to open more financing channels for the country’s smaller companies, including SME loan guarantees and extensions on loan maturities. The measures will help some companies, explains Standard & Poor’s Japan bank analyst Naoko Nemoto, but could ultimately result in more defaults, higher government costs and lower bank profitability. “The loan guarantees and extended maturities allow very weak corporations to remain in the marketplace, and their eventual defaults will cost taxpayers. The guarantees are also provided for very low fees, pushing down interest margins,” she says.

The policies also allow banks to hide troubled assets, increasing risks and undermining confidence in banks. Nemoto continues: “If banks extend maturities, then they can put off disclosing problem loans. The transparency then is weakened, and we have less confidence in banks’ numbers. Regional banks’ non-performing loan numbers are declining, but analysts are very skeptical about this.”

Lack of transparency is a problem not only for banks and current lenders but for potential borrowers as well. This transparency issue impairs banks’ capabilities to assess risk and discourages the flow of capital to Japan’s SMEs, according to members of the banking and finance committee of the American Chamber of Commerce in Japan. Credit information in Japan can be difficult to obtain, and restrictions on using that information can complicate efforts to build effective scoring models. “Lenders need a clear, transparent, universally accessible full file credit database tracking system,” say committee members. “In Japan, the system has historically been very heavily siloed with very limited sharing of information across sectors. While there have been recent positive moves to drive a more coordinated regulatory framework on credit bureaus, there is still very little ability to use that information to do decision science or risk management.”

The opacity of borrowers also reduces the incentive for those borrowers to pay back their loans. The chamber of commerce also points out that a moral hazard problem exists because there is no benefit to paying on time. The lack of transparency for current and potential borrowers coupled with the lack of reward for good behavior discourages banks from extending loans to SMEs, despite the government’s SME programs.

The inefficiencies in Japan’s financial system will take time to correct. Prime minister Hatoyama and his Democratic Party of Japan are only a few months into office, and they appointed a new finance minister just last month. The party’s popularity remains relatively high but could erode quickly if its policies do not encourage progress on the tough issues facing the country.

Still, the election of a new party, regardless of the success of its policies, will bring more diversity into Japan’s political realm and potentially more dynamism to its economic structure. That dynamism will be needed, as the past 18 months have shown, to respond to the complex challenges brought by the increasingly dynamic global economy.