CORPORATE FINANCING NEWS: FOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

The dollar has been in a long-term declining trend against the major currencies for nearly a decade, losing about 40% in value, but analysts say it is no longer weakening in periods of increased risk appetite, and the greenback appears to have embarked on a new long-term bull market.

The complete breakdown of the relationship between relative interest rates and the dollar’s value against the Japanese yen, and the declining link between the dollar and equities represent notable shifts in market behavior, according to Bilal Hafeez, strategist at Deutsche Bank in London.

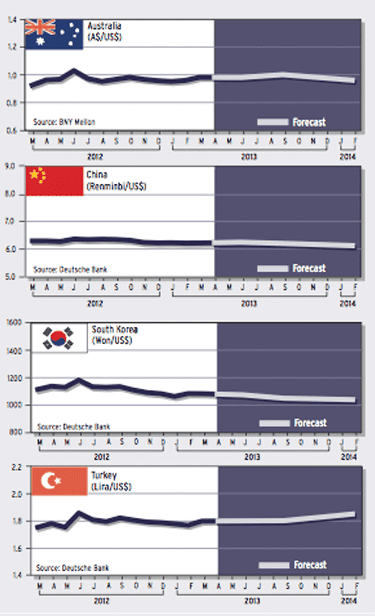

“Superior US growth should support the rotation from bonds to equities that will help the dollar,” Hafeez says. In addition, the recent actions to defeat deflation by the new Shinzo Abe government in Japan demonstrate the scope central banks outside the US have to weaken their currencies against the dollar. “China rebalancing away from investment provides a downside risk to the China-linked currencies that have done so well since 2008,” he adds. “All these trends are intertwined and together point to sustained dollar strength.”

EURO TUMBLES

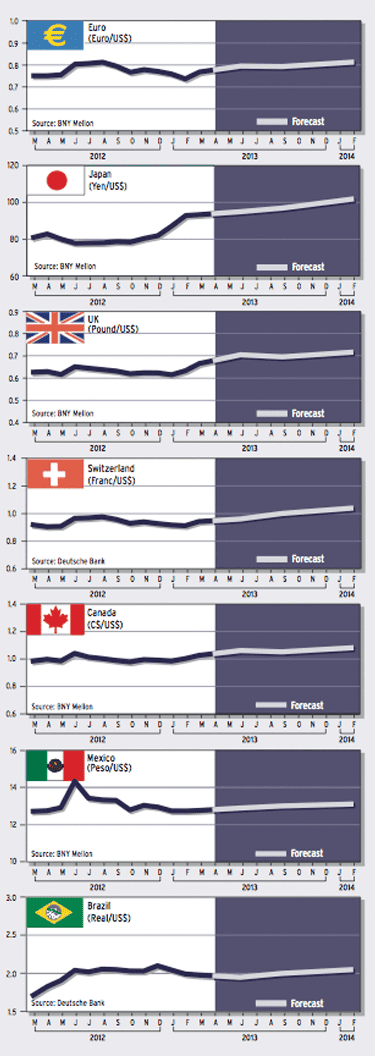

The euro fell to a three-month low against the dollar in early March, and Deutsche Bank expects it to slide to just above parity with the dollar by 2015, by which time it expects the yen to weaken to 115 to the dollar.

Alistair Cotton, senior analyst at Currencies Direct, a London foreign exchange broker and international payments provider, says: “Italy’s election, which resulted in a hung parliament, weakened the euro. Market participants want Italy to get an economic plan in place and to stick to it. They are worried about Italy’s inability to make tough decisions.”

The British pound has also fallen sharply against the dollar so far this year, heading toward a three-year low, according to Cotton. Mark Carney, who will take over from Mervyn King in July as governor of the Bank of England, gave a speech to members of Parliament, laying the foundation for his expected moves toward a more pro-growth stance, although any changes are likely to be minor, Cotton says. King also expressed his view that a low exchange rate would be preferable and that the central bank could tolerate higher inflation. King surprised the markets by voting for an increase in stimulus at the February meeting of the monetary policy committee. The increased stimulus was outvoted by a three-to-six margin.

Moody’s Investors Service became the first major ratings agency to strip Britain of its coveted triple-A credit rating. Investors should not be surprised if other major ratings agencies make good on their negative outlooks for the UK, with further downgrades likely to follow, analysts say.

LEAST-UGLY CONTEST

Federal Reserve chairman Ben Bernanke has indicated that US interest rates will stay low, Cotton notes. “The US economy is chugging along nicely, and the improving economy is going to be dollar-positive going forward,” he says. “It’s almost the ugly sisters again—the dollar is the best of a bad bunch.”

Humayun Shahryar, CEO of Auvest Capital Management, a global alternative investment firm, says: “Taking any view on the euro is pure gambling because the euro’s exchange rate is based on politics, not economic fundamentals. Whoever comes to power in Italy will have to deal with structural issues, such as the aging population and competitiveness.”

The uncertainty surrounding the Italian election suddenly brings the whole euro cohesiveness issue back on the table, Shahryar says. “What these [peripheral European] countries need is debt forgiveness.” That is unlikely to happen unless there is a major crisis and a shakeup, he adds.

SHORTAGE OF DOLLARS

“The dollar is back in a structural bull market, not because the US economy is recovering, but because we are in a deleveraging cycle, which creates a shortage of dollars,” Shahryar says. “The shale oil and gas revolution in the US, making the country more energy-independent, will also reduce the supply of dollars outside the US.”

China and Germany—the major exporting countries—will suffer because they cannot export deflation all over the world, according to Shahryar. “There is too much manufacturing capacity relative to demand.”

Japan posted a record $17.4 billion trade deficit in January, as the weak yen pushed up the cost of importing oil. “The biggest threat to the global financial system is that Japan will start relying on foreign capital to fund its debt,” Shahryar says, adding that Japan is a $5 trillion economy and cannot be allowed to collapse. Foreign central banks will buy Japanese government bonds, he says.

GLOBAL CURRENCY WARS

The investment community has had a “eureka” moment, according to John Hardy, head of FX strategy at Saxo Capital Markets, realizing that in a world of fiat currencies backed by nothing, in addition to weak demand for manufactured goods, the winner is the country that devalues its currency the most. “With the advent of Japan’s LDP [Liberal Democratic Party] last December, the global currency wars were engaged. This is leading to investment opportunities in the foreign exchange market.”

Since Abe’s assumption of office, the yen has fallen sharply. “Japan has been the first mover with its overt promotion of currency policy to a matter of vital national interest,” Hardy says. “The move is an act of international economic aggression that will have repercussions.”

Central banks have become politicized, which has already become apparent in Japan and is about to come to the West, if Carney implements radical new efforts to help the UK economy achieve “escape velocity” upon his arrival at the Bank of England, according to Hardy: “The market is also in the process of making the uncomfortable transition from the former paradigm of merely bidding up all risk assets on the theory that central banks will forever provide a free ride, to the new paradigm driven by the implication of global currency wars, as nation after nation moves aggressively to get the upper hand in the mud-wrestling match of competitive devaluation.”

MAJOR DISTRACTION

But not everyone agrees that currency war is the new norm. One of the dangers of exaggerating currency wars is that it distracts our attention from the real systemic fissures, says Marc Chandler, global head of currency strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman. “Unlike the 1920s and 1930s, the critical fissure is not between countries (as was the case in the aftermath of [the] World War), but within countries,” he says. “The domestic elites have turned on their own people. Capital accumulation and profits are largely being preserved at the cost of further erosion of the social contract and the increased concentration of income and wealth domestically.”

The international order may be more robust than many have argued, according to Chandler. “The existence of circuit breakers and conflict-resolution mechanisms like the World Trade Organization reduce the chances of currency tension spilling over into trade,” he says. “This, in turn, underscores our belief that the role of the dollar in the international economy as a reserve asset, a store of value and a means of exchange has not and will not be significantly altered by the financial crisis.”

The yen’s weakness was a function not only of the change of regimes in Japan but of actions of the European Central Bank last summer to ensure the survival of the European monetary union (EMU) project, which reduced the need for safe havens in general, and this was clearly a force much larger than the yen, Chandler says. “As the LDP seemed to have demonstrated previously, monetary and fiscal stimulus in the absence of structural reforms is not effective under current conditions in Japan.”

Meanwhile, Japanese investors are keeping more of their investments at home, Chandler notes. “It seems as if the realization that their yen can buy few foreign assets has caused a bit of sticker shock and they have been selling foreign assets,” he says. “The inability to recycle the current account and portfolio capital inflows may exert upward pressure on the yen.”

Previously, Japan had problems recycling its trade surplus. “This entailed selling yen to offset the yen coming into the country as a product largely of its trade surplus,” Chandler says. “Then, there was a greater understanding that the investment-income surplus (from coupons, dividends, royalties and licensing fees) was a key driver of the external surplus (current account). Now, the new interest from foreign investors, who were forced to chase the Japanese stock market higher as the yen weakened, adds a new dimension to the old recycling problem.”

DOMESTIC OBJECTIVES

Prime minister Abe chose Haruhiko Kuroda, the current president of the Asian Development Bank, to become the next governor of the Bank of Japan. “Abe appears to have picked the official to head up the BOJ who has the highest international gravitas, and Japan seems to be more likely to join the trans-Pacific free-trade agreement,” Chandler says. “The pursuit of monetary and fiscal policies for domestic objectives is not tantamount to war. Japanese officials have moved back within compliance by not citing specific bilateral exchange targets.”

In addition, Japanese officials have played down the need to buy foreign bonds, which is too close to foreign exchange intervention, Chandler says. They have also shown less urgency to change the BOJ’s charter, he says.

Japan reported that its inflation fell for the eighth time in nine months in January, with its consumer price index down 0.3% from a year earlier. Says Chandler: “The new BOJ team has its work cut out for itself to achieve 1% CPI [inflation] let alone 2%.”