CORPORATE FINANCING NEWSFOREIGN EXCHANGE

By Gordon Platt

Dollar Weakens As Eurozone Rates Are First To Rise

Differing monetary policy reactions to the rise in oil prices are driving currency values at the moment, while gains in the Japanese yen have been capped by intervention by the Group of 7 industrialized countries. The dollar will continue to weaken, and the euro will rise further in anticipation of more interest rate hikes by the European Central Bank later this year, analysts say.

The ECB raised its benchmark interest rate by 25 basis points to 1.25% on April 7 to combat inflation, while the Federal Reserve is still easing monetary policy through unconventional purchases of US government notes and bonds and is unlikely to raise rates before next year at the earliest.

At his press conference last month, ECB president Jean-Claude Trichet signaled that further rate increases are likely. Asked about second-round effects on inflation from German wage increases, Trichet said the bank is extremely alert to this possibility and would do everything it possibly could to keep this from happening.

Aggressive Tightening

Trichet offered little new to a market that already has assumed there will be an aggressive ECB tightening cycle, says Lena Komileva, London-based global head of G10 strategy at Brown Brothers Harriman. “Risks to the growth outlook remain balanced, with the ECB clearly taking the core view that the contagion from escalating tensions in Portugal and Ireland onto the rest of the eurozone will remain limited,” she says.

Komileva says the ECB will continue to provide unconventional policy support, but even here the direction is toward further policy normalization, even as Portugal was forced to seek aid to avoid a default and EU governments are increasingly prepared to accept the inevitability of a Greek debt restructuring. “It is clear that the ECB’s strategy is to maintain control over inflation expectations, by launching a gradual process of policy normalization,” Komileva says.

The market’s assumptions about additional rate increases by the ECB this year may be excessive, she says. “A higher cost of borrowing and a stronger euro will only force a more prolonged depression in the uncompetitive, debt-laden euro area economies, leading to a costlier restructuring,” she adds.

Fed’s Dual Mandate

Unlike the ECB, which concentrates solely on price stability, the Fed looks at so-called core inflation, which excludes volatile food and energy prices. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC), which sets monetary policy, also has a dual mandate, meaning that it takes economic conditions, especially unemployment, into account as well as inflation.

“On the day after the caretaker government in Portugal went hat in hand to the public, announcing that it had no alternative but to seek a bailout from the EU’s European Financial Stability Facility, the ECB did what the Bundesbank would do,” says David Gilmore, partner and economist at Foreign Exchange Analytics, based in Essex, Connecticut. “With inflation at 2.5%—above its 2% target—it hiked.”

This spoke volumes about the premium the ECB puts on its independence and, of course, on its single mandate of price stability, Gilmore says. Trichet’s reiteration that the ECB did not decide on a series of rate hikes in advance did not prevent the markets from expecting three hikes this year and three more next year, he says. “That’s because everyone knows what the Bundesbank would do,” Gilmore says.

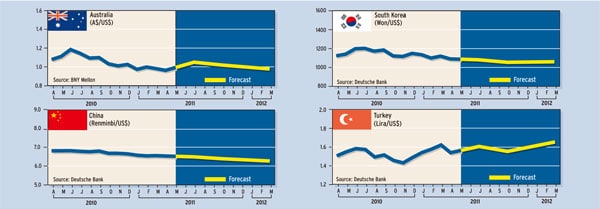

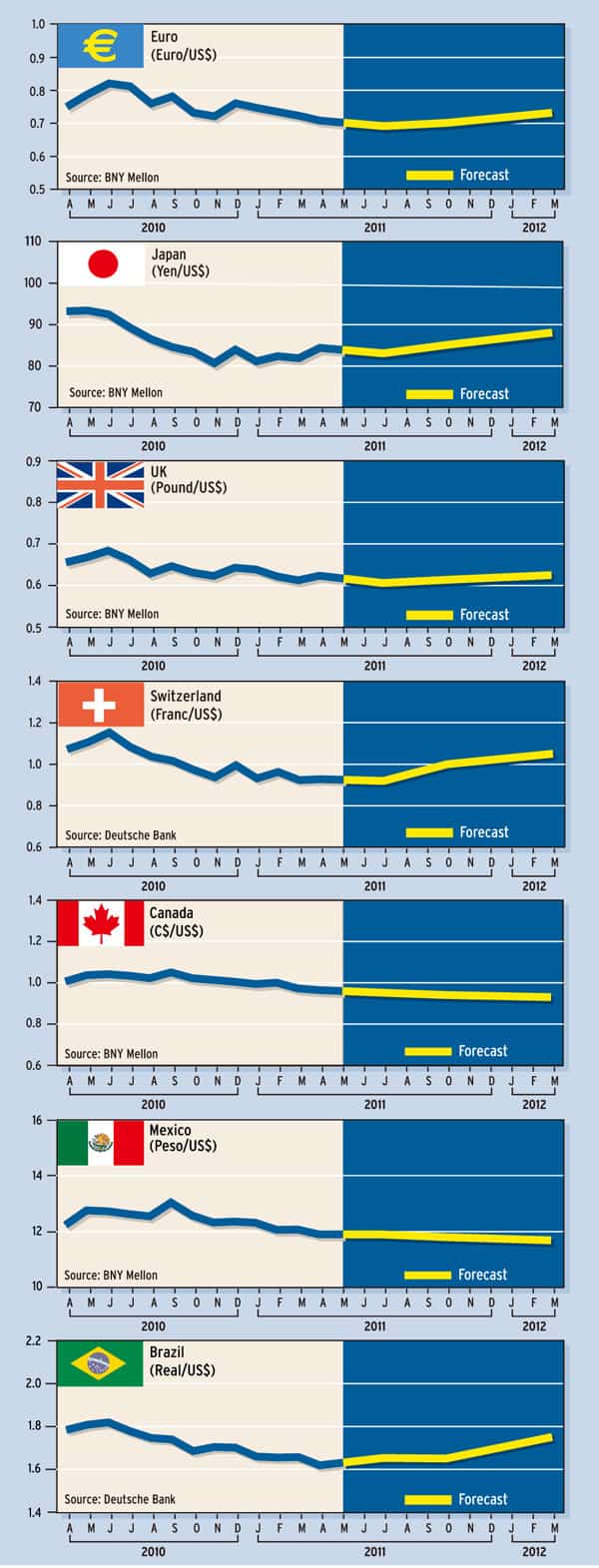

Currency Forecasts

No ECB Lifeline

In time markets will see a Bundesbank monetary policy as no lifeline for a structurally flawed, multi-speed eurozone and its restless population, Gilmore suggests. “We have not seen either the end of the periphery debt crisis nor a metamorphosis for the euro,” he notes.

As soon as the FOMC decides the dollar has fallen enough and the wealth effect from rising stock prices has played out and the committee signals the removal of Fed accommodation, the euro will take its rightful place as an ugly currency alongside the dollar, Gilmore asserts, adding that the build-up of emerging markets’ currency reserves, not the Fed’s quantitative easing, is the main culprit for the inflation impulse. While there is a common perception that the Fed is sowing the seeds of hyperinflation, dollar debasement and a coming apocalypse, Gilmore points out that the money the Fed is pumping into the banking system only gets parked in excess-reserve accounts at the Fed and does not get turned into investment and consumption.

A major source of liquidity for risk assets is coming from reserve managers in the emerging world, according to Gilmore. China’s 5% per year appreciation of the renminbi is about equal to the current rate of inflation, which means there is no real exchange-rate appreciation, he says. “China won’t turn back, and ultimately will bring a massive surge in domestic inflation and an end to the vastly overestimated success of the world’s largest centrally planned economy,” he says.

Huge Fiscal Deficits

Central banks are responding to increasing inflationary pressures in markedly differing ways, says Paul Robinson, London-based European head of FX research at Barclays Capital. Fiscal deficits are huge, and governments are taking widely divergent approaches to the issue, while commodity price moves could have much further to go, he says.

“The world may have recovered, to a large extent, in flow terms from the financial crisis, but it cannot be viewed as being in a steady state,” Robinson believes. “As it continues to rebalance, currencies are likely to carry on playing an important role.”

US monetary policy looks set to remain extremely loose, which is likely to maintain the downward pressure on the dollar. This should be of little surprise to the market, however. “Indeed, US growth may surprise to the upside, in our view, which will not lead to early tightening but may increase future expected interest rates and, therefore, offer some support to the dollar,” Robinson says.

Fiscal policy is less likely to support the dollar, however, he says. “The US is not alone in having a fiscal deficit that is much larger than is consistent with long-run fiscal sustainability, but it does appear to face more complicated political issues than the other large-deficit economies,” Robinson says.

Currency Forecasts