Even as the pandemic fades, the GCC states will be challenged to revive their economies and again pursue regional integration.

Once a symbol of regional economic and political confidence, the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) faces an uncertain way forward, still shaken by the biggest dispute in its 40-year history. Despite the ending of a futile blockade of Qatar that took the six-member bloc to the brink, and despite the bonhomie that followed the Al-Ula Declaration that proclaimed the crisis over, deep divisions and lingering enmities remain.

And the GCC’s sternest tests may lie ahead. Last October, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) projected that the dual impact of Covid-19 and lower oil prices would wipe around $150 billion off GCC oil exports, a 37% decline from 2019.

Whether the GCC has the collective resolve to address its members’ structural economic problems, rather than continue a fickle policy confined to major issues driven by national interests, is the fundamental question, close observers say. Most likely is “a scenario wherein the process of enhancing regional economic integration will be transactional and opportunistic rather than by systematic design,” says Robert Mogielnicki, resident scholar at the Arab Gulf States Institute in Washington, DC.

The IMF forecast, in October, that the GCC economies would contract 6% in 2020 with GDP growing by just 2.3% in aggregate this year, is slower than other emerging market economies. But the pandemic has accelerated the need for wider economic reforms as the region edges closer to peak oil production and a global energy transition. Borrowing levels in the GCC rose steeply last year; while over $100 billion of government debt is projected to mature between 2021 and 2025, according to the IMF.

Constraints

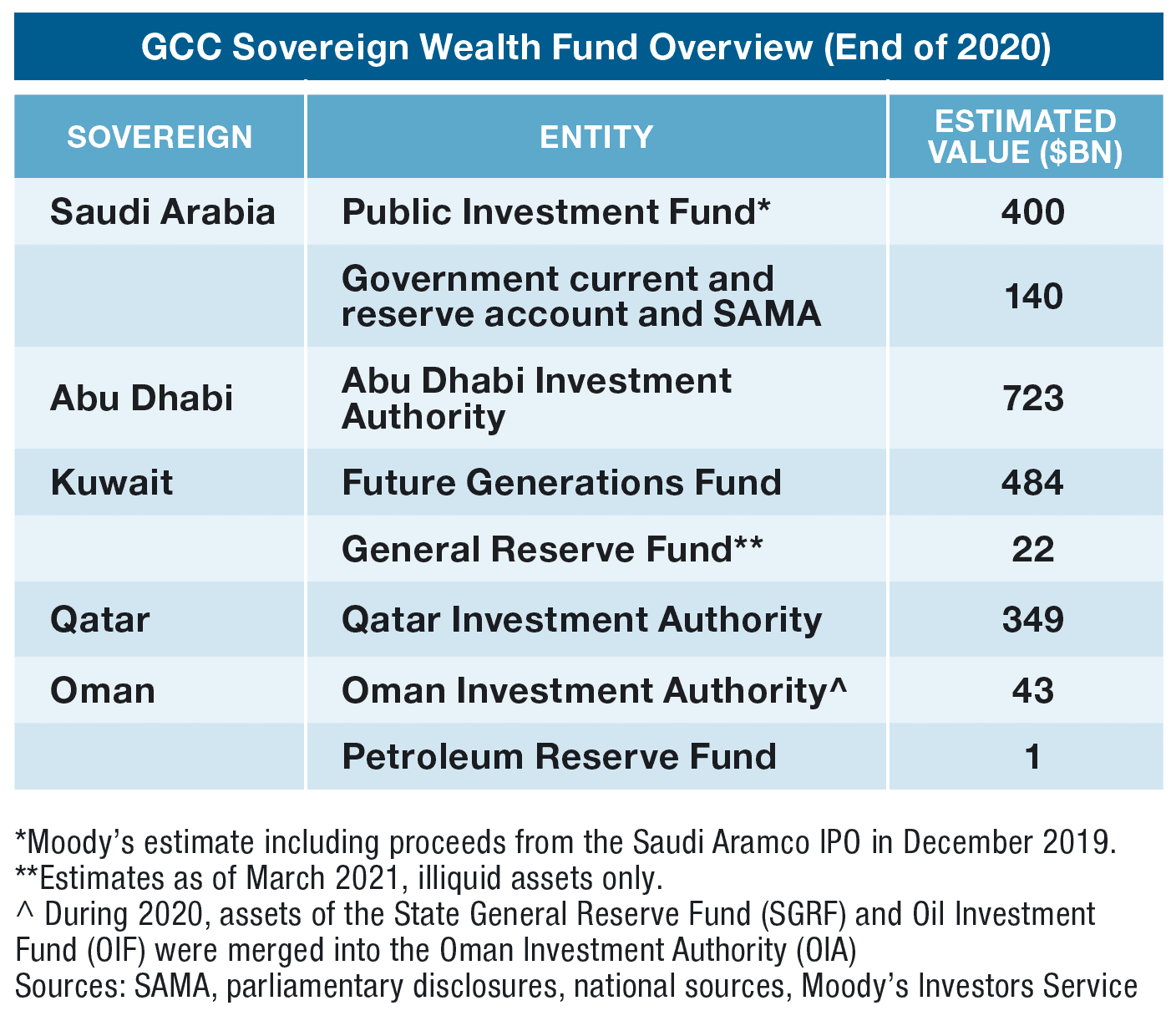

Budget constraints limit governments’ leeway to boost spending in pursuit of higher growth; and although GCC sovereign wealth fund (SWF) capital buffers are ample in Kuwait, Qatar and the United Arab Emirates (UAE), they are weaker in Saudi Arabia and Oman. Government debt burdens in Oman and Saudi Arabia now exceed their liquid SWF assets, according to Moody’s Investors Services. Bahrain does not have access to liquid government assets that could be used for deficit funding, (See chart).

All GCC states are projected to run fiscal deficits this year; Kuwait faces a liquidity crunch that may see its deficit spiral to more than 30% of GDP, Moody’s estimates. Bahrain’s interest burden will represent more than one-quarter of revenues, according to Moody’s, and government debt ballooned to 133% of GDP last year.

All GCC economies are therefore under pressure to rein in spending, cut the public sector and rewrite a generous social compact. Already chronically high, youth unemployment has surged during the pandemic. In Saudi Arabia, the Gulf’s largest economy, the jobless rate among the 15-to-24 age group exceeded 30% toward the end of last year, according to Capital Economics. Left unchecked, unemployment threatens regional stability.

But weaning nationals off well-paid government employment is easier said than done, as pay differentials between the public and private sectors range as high as 50%. With the exception of Oman, Qatar and the UAE, public sector wages in the GCC are well above the 10% of GDP seen in advanced economies.

And fatter salaries do not correlate with better services. All GCC countries except the UAE and Saudi Arabia have witnessed a deterioration in the quality of public services over the past five years despite significant increases in wages, the IMF says. To stem the economic fallout from the pandemic, GCC governments moved quickly with a raft of measures including slashing taxes and fees, cutting interest rates, extending loan deferrals and injecting funds to shore up the banking system. But at just over 1% of Gulf GDP, the aggregate fiscal boost has been much smaller than in other regions.

There is no shortage of vision for a recovery; indeed, “vision” may be the most overused word in discussing Gulf currently. In the quest for economic diversification, government diktats have spawned high-profile initiatives including Bahrain’s Economic Vision 2030, Oman’s Vision 2040 and Saudi Arabia’s Vision 2030.

Yet, Gulf governments still rely heavily—more than 70%, in some cases—on oil and gas revenues. Structural problems, including an unwieldy legal and regulatory environment, high labor costs and skills shortages hamper broader private sector growth, says Krisjanis Krustins, director and GCC sovereigns analyst at Fitch Ratings.

“GCC non-oil economies rely on the same narrow set of sectors, many of which are facing their own challenges: for example, real estate, aviation and logistics,” he says. In short, to be globally competitive, the GCC states need to repurpose their value proposition and further liberalize their economies.

Trophy projects abound. Saudi Arabia recently unveiled a $100 billion to $200 billion, 105-mile-long smart city dubbed “The Line”—part of the even larger Neom project: a $500 billion, 10,000-square-mile, carbon-free megacity. But earlier projects such as the smaller King Abdullah Financial District failed to lure banks and financial services firms.

Despite recent reforms, foreign direct investment (FDI) in the kingdom is falling. The government has targeted FDI to reach 5.7% of GDP by 2030; but last year it slumped to just 0.6%, says Capital Economics.

In a bid to break the impasse, Riyadh has ruled that from 2024 authorities will stop awarding government contracts to companies whose Middle East headquarters are located elsewhere in the region. Whether the move is perceived as predatory or a way to enlarge the regional market is not yet clear.

“I don’t view the main thrust of this measure as a direct challenge to the UAE or Bahrain,” says Mogielnicki. However, “The Saudi government is putting global businesses on notice it wants more in-country value for every riyal spent.”

Undeniably, however, the challenges faced by the GCC are prompting some governments to embrace changes that previously would have been unthinkable. The UAE, the first Gulf state to normalize ties with Israel last year, also announced it will grant citizenship to selected investors and professionals in certain categories, a move described by some as unprecedented. The regional battle for FDI and talent may be just beginning.

Banks Under Pressure

Banks and financial institutions have borne the brunt of the downturn, and some have extended support measures. Fitch sees a risk of a deterioration in GCC banks’ asset quality as they delay recognition of Stage 3 loans: those deemed credit impaired under the International Accounting Standards Board’s IFRS 9 loss provisioning standards.

Kuwaiti and Saudi banks remain resilient, however, given their pre-pandemic credit fundamentals and low levels of impaired loans. The Saudi government injected about $26 billion, or 4% of GDP, into the domestic banking system between March 2020 and February of this year. But loan quality looks more vulnerable in the UAE due to high levels of Stage 3 loans and deferred exposures, Fitch notes.

Furthermore, hard-currency debt issued by Gulf financial institutions rose to a record-high $35.6 billion in 2020 from $29.6 billion in 2019, according to Fitch, citing First Abu Dhabi Bank. Despite their relatively strong buffers, GCC banks remain risk averse, which may act as a drag on economic recovery as credit remains unavailable to many small to midsize enterprises.

High-frequency indicators, and particularly purchasing manager indexes that gauge business confidence, show contrasting trajectories. Still, GCC banks seem to have taken a prudent approach to provisioning for expected credit losses in anticipation of weaker credit conditions.

Given the tensions always present in the Gulf, political concerns loom large over GCC governments’ economic worries. US-GCC relations face a reset under US President Joe Biden’s new administration; but the elephant in the GCC’s living room remains Iran, arch foe of the region’s two largest economies, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. February’s US intelligence report claiming Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman approved the murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi is a setback for the kingdom’s efforts to contain Tehran’s regional ambitions.

In a sign of differences over future strategy, Qatar recently recommended establishing a GCC dialog with Tehran, with which the emirate shares the largest gas reserves in the world. And while the decision by the UAE and Bahrain to normalize relations with Israel has set many a regional analyst’s mind aflutter, it is unlikely other GCC states will follow suit. Meanwhile, renewed global urgency to confront climate change and boost renewables will hasten a pivot away from hydrocarbons.

Will this brew regional conciliation, or further dissension? The region’s economic recovery may well depend on the answer.